Vaccine stops deadly sand-fly-spread scourge in animal test

DNA immunization protects hamsters and mice from Leishmania parasite

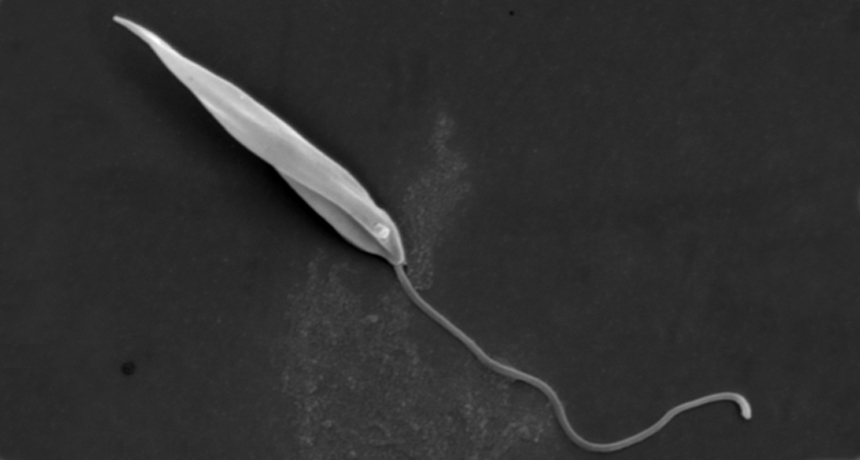

PREPPING FOR INVASION Preventing the Leishmania donovani parasite (shown, untreated) from hijacking heme from its hosts may be key to creating a vaccine to combat the scourge.

L.R. Haines et al/PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2009