What does Mars’ lake mean for the search for life on the Red Planet?

The water body, if confirmed, could potentially harbor microbes

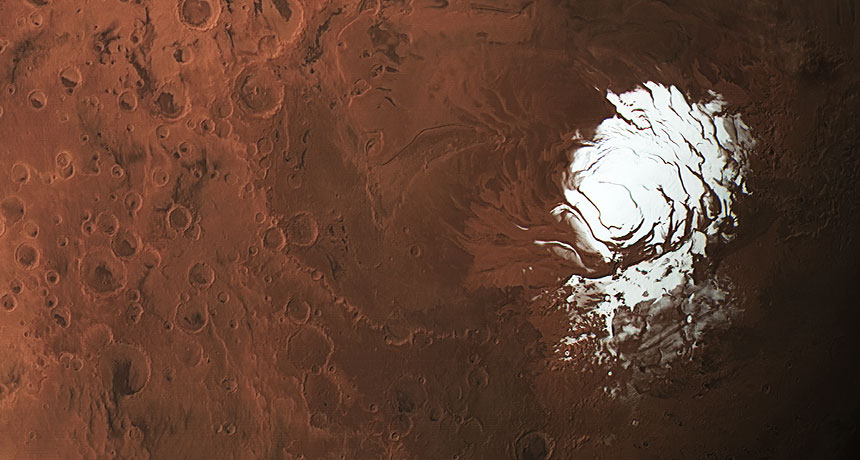

WHAT LURKS BENEATH Scientists think they’ve spotted a lake hidden under ice (white) near Mars’ south pole, shown in an image from ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft.

ESA, DLR, FU Berlin (CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

The search for life on Mars just got a lot more interesting.

For decades, scientists have looked at the dry and dusty planet and focused on finding regions where life could have taken root billions of years ago, when the Martian climate was warmer and wetter. But on July 25, researchers announced they had spotted signs of a large lake of liquid water hiding beneath thick layers of ice near the Red Planet’s south pole (SN Online: 7/26/18).

If the lake’s existence is confirmed, we could find microbes living on Mars today.

That report changes the calculus for astrobiologists who want to protect any existing extraterrestrial life from being wiped out or obscured by introduced species from Earth (SN: 1/20/18, p. 22). Mars landers and rovers are cleaned to strict standards to avoid any possible contamination, even “without having anything you’d even call a pond,” says astrobiologist Lisa Pratt, NASA’s planetary protection officer. “Now we have a report of a possible subglacial lake! That’s a major change in the kind of environment we’re trying to protect.”

So how does finding the lake change the quest for life on Mars?

First things first: Could anything actually live in this lake?

It would be a tough territory for most earthly microbes. Life on Earth fills every niche it can find, from cave crystals to arid deserts (SN: 3/31/18, p. 14). But the low temperature cutoff for most terrestrial life is around –40° Celsius. The Martian ice sheet is about –68° C. “It’s very cold, colder than any environment on Earth where we believe life can either metabolize or replicate,” Pratt says.

The lake does seem to contain plenty of water. But for the water to be liquid at such cold temperatures, it must be extremely salty. “On Earth, these kinds of briny mixtures present significant challenges to living organisms,” says planetary scientist Jim Bell of Arizona State University in Tempe, president of the Planetary Society. “Even ‘extremophile’ bacteria that can live in highly salty water might not be able to survive.”

But could Martians live there?

“Absolutely,” Pratt says.

If life arose on Mars sometime in its more life-friendly past, some organisms could have adapted to the changing climate and ended up finding the cold, salty water quite comfortable, she says. “This to me looks like an ideal refugia, a place where you could just hang out, maybe be dormant, and wait for surface conditions to get better.”

What’s different about this lake versus other watery places where we hope to find life, like Saturn’s moon Enceladus?

For planetary explorers, Mars has one major advantage over the icy moons of Saturn and Jupiter: We’ve landed on it before. Getting to Mars is a relatively quick journey of about four to 11 months, and the planet’s atmosphere makes landing much simpler than on the tiny, airless moons.

The big question for planetary protection is whether Mars’ lake has any contact with the surface. On Saturn’s moon Enceladus and possibly on Jupiter’s moon Europa, liquid water from a subsurface ocean sprays into space from cracks in the ice (SN: 6/9/18, p. 11). Those plumes could make sampling the oceans relatively simple: A spacecraft could just catch some spray during a flyby. But the fact that water can get out means that invading microbes can get in.

Even though no Mars spacecraft has landed near the lake, global dust storms — like the one currently raging on Mars — could carry contamination from anywhere on the planet (SN Online: 6/13/18).

“So if [the lake is] real, let’s hope there’s no passageway into it,” Pratt says.

If there’s no way in or out, how can we see if anything lives there?

There’s the rub.

To check the lake for signs of life, “you gotta drill,” says planetary scientist Isaac Smith of the Planetary Science Institute, who is based in Lakewood, Colo. That’s how scientists have probed similar under-ice lakes on Earth, such as Lake Vostok in Antarctica, which Russian scientists drilled into in 2012 (SN: 11/7/13, p. 26). That team controversially claimed that the lake hosts a thriving ecosystem, although later the researchers admitted that the samples were contaminated with drilling fluid.

Drilling on Mars would be even more technically challenging, and could face opposition from the scientific community, as the Russian team did. “Like the subglacial lakes in Antarctica, [the Mars lake] would be considered an extraordinarily rare and special place,” Pratt says. “I expect there would be lots of resistance to drilling into it.”

But if we’re lucky, there could be a sign from above. Signs of seasonal methane variations in the Martian atmosphere have piqued astrobiologists’ interest as a possible sign of microbial life under the surface (SN: 7/7/18, p. 8). The European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, which began taking data in April, is looking for more methane.

“ExoMars could find a smoking gun, so to say,” says planetary scientist Roberto Orosei of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Bologna, Italy, who was on the team that discovered the lake. “Association of liquid water and methane in the atmosphere would be very, very exciting evidence of something going on on Mars.”