PENGUIN PERIL Juvenile African penguins (shown) forage for their own food when they leave the nest. Some from the Western Cape of South Africa become trapped in areas without any fish, a new study finds.

SANCCOB

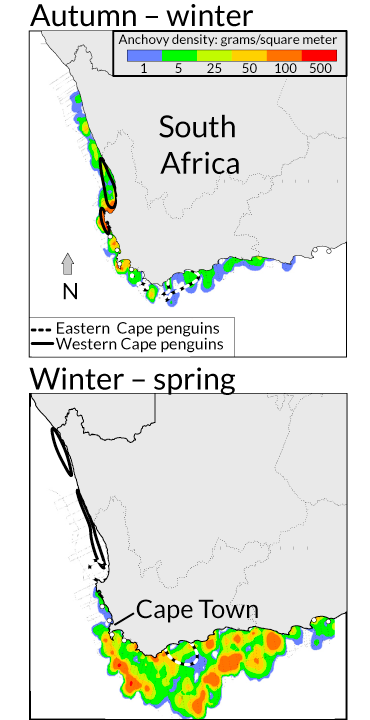

African penguins have used biological cues in the ocean for centuries to find their favorite fish. Now these cues are trapping juvenile penguins in areas with hardly any food, scientists report February 9 in Current Biology.

It’s the first known ocean “ecological trap,” which occurs when a once-reliable environmental cue instead, often because of human interference, prompts an animal to do something harmful.

When juvenile Spheniscus demersus penguins off the Western Cape of South Africa leave the nest for their maiden voyage at sea, they head for prime penguin hunting grounds. But the fish are no longer there, says Richard Sherley, a marine ecologist with the University of Exeter Environment and Sustainability Institute. Increased ocean temperatures, changes in salinity and overfishing have driven the fish eastward.

Penguins are doing what they’ve evolved to do, following signs in the water to historically prosperous habitats. “But humans have broken the system,” Sherley says, and there’s no longer enough fish to support the seabirds.

Sherley estimates that only about 20 percent of these African penguins survive their first year, partly because they can fall into this ecological trap.

Ecological traps have been documented on land for decades. There has been a lot of speculation about traps in the ocean, but this study is the best evidence so far, says Rob Hale, an ecologist with the University of Melbourne.

“Hopefully the study will generate more interest in examining ecological traps in the ocean so we can better understand when and why traps arise, how they are likely to affect animals, and how we can go about managing their effects,” Hale says.

This trap may have occurred because of how penguins find their food. Researchers think penguins can sense a stress chemical that phytoplankton release when being eaten. Penguins eat sardines, which eat phytoplankton. Usually the chemical, dimethyl sulfide, signals to penguins where the fish are feasting on phytoplankton. But phytoplankton can release the compound in other situations, like in rough water. The signal is still sent, but there are no fish.

“You have a cue that used to signal high quality in an environment, but that environment has been modified by human action to some extent,” Sherley says. “The animals are tricked or trapped into selecting a lower quality habitat because the cue still exists, even though there’s high quality habitat available.”

Adult penguins have adapted to the trap and shifted their hunting patterns to follow the fish east. Sherley says they’re not sure how adults learned to avoid the problem, but that there must be a way that juveniles who survive to adulthood also adapt.

Researchers also tracked juvenile penguins from the Namibia and Eastern Cape of South Africa breeding regions. The eastern penguins have been unaffected by the trap because the fish have moved closer to them. The Namibia population is being barely sustained by the goby, a junk food fish that appears to be taking over the areas previously inhabited by sardines and anchovies.

The Western Cape penguins have been most affected. The population has declined 80 percent in the last 15 years — from 40,000 breeding pairs to 5,000 or 6,000, Sherley says. He estimates that if juvenile penguins hadn’t been falling victim to this trap, the Western Cape population would be double its current levels.

If the loss of fish off the Western Cape of South Africa can’t be reversed, Sherley speculates the two most likely outcomes are an African penguin extinction or an ecosystem shift. Current penguin conservation efforts protect penguin breeding areas, but the study suggests that the protections may be insufficient because the ecological trap is far from the breeding grounds.