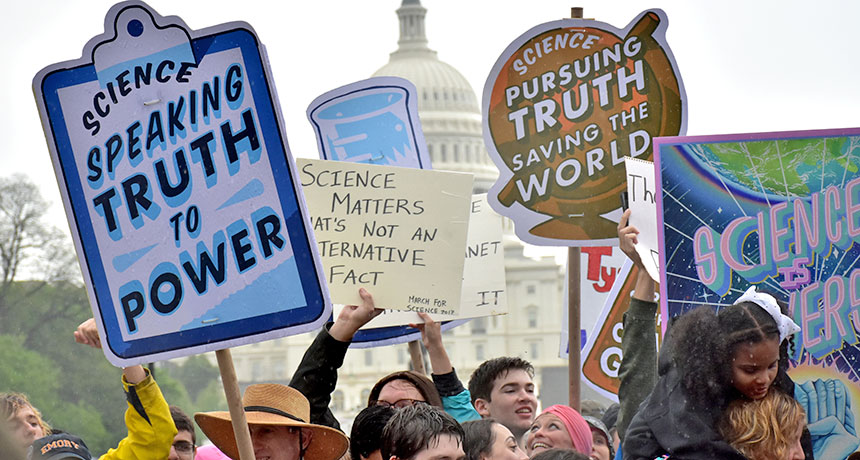

An antiscience political climate is driving scientists to run for office

The same pro-science wave driving the March for Science is driving greater activism

CLIMATE CHANGE Hundreds of scientists have moved beyond marching and are now hoping to storm Washington (and beyond) as politicians.

Amaury Laporte/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The upwelling of science activism witnessed in last year’s March for Science led many to predict that a flood of scientists might leave the lab for the legislature. Now, on the eve of the second March for Science, a survey of the field suggests that’s the case.

As many as 450 scientists-turned-politicians are throwing their hats into state, local, and federal campaigns, according to 314 Action. The advocacy group (named for the first three digits of pi) encourages and supports people with science and technology backgrounds interested in running for office.

Founded in 2016, the group saw a huge surge in interest after Donald Trump was elected president, says 314 Action spokesperson Ted Bordelon. As many as 7,000 potential candidates reached out to 314 Action, though the realities of running have winnowed that number down.

“The attacks on science certainly didn’t start with Trump,” Bordelon says. “But he has been a huge catalyst. That may be one of the bright spots of his presidency — more scientists saying they want to be in the ring when it comes to lawmaking.”

With midterm elections looming this fall, some 25 scientists are running at the federal level. Depending how you count, that’s more than double the current number of science-trained members of Congress, not including physicians. The candidates’ backgrounds run the scientific gamut from aerospace to neuroscience to epidemiology.

One candidate is biochemist Randy Wadkins. His first hankering to run for office began in 2015 when he took a year off from teaching and research to work as a congressional science fellow. Watching members of Congress from poor states like Mississippi vote against health care funding was “shocking,” he says. “I couldn’t understand the logic and I came back frustrated.”

President Trump’s proposed cuts to science funding propelled Wadkins, a Democrat, to run for Mississippi’s 1st Congressional District seat despite the strong Republican demographics of his district. On his campaign website, Wadkins bills himself as “A new kind of Democrat: optimist, pragmatist, scientist.”

“It’s time to stop the antiscience, anti–health care approach,” Wadkins says.

Another scientist aiming for the ballot this fall is physicist Elaine DiMasi. She has spent decades studying the crystalline structures of biological materials such as seashell minerals at the Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, N.Y. Growing frustration with government shutdowns, a huge disruption to national labs like Brookhaven, partly spurred her candidacy. “Then, after Trump was elected, I thought, ‘I have a nice job, I’m tenured, I’m safe,’ but I felt so pessimistic.” Now she’s running for the 1st Congressional District of New York on Long Island.

Many of their fellow scientists’ campaign messages echo similar themes: despair and dismay with a government that over many years has given science short shrift and cast evidence-based reasoning to the wind. These concerns are legitimate, says physicist Rush Holt, who served eight terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and now heads the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“There is hardly a public issue that does not have scientific components — election laws, public health, transportation, economics — almost every issue can be illuminated by scientific findings and evidence-based thinking,” Holt says.

Legislators may ask for scientific input on explicitly scientific issues, like NASA’s budget. But “in all these other issues, where science is embedded but not obvious, science is neglected,” Holt says.

DiMasi cites science-driven policy as a driving force in her candidacy. “Evidence-based politics is what I care about. I don’t care if it comes from the right or the left or the other right or the other left. As scientists, we are trained to prove ourselves wrong,” she says. “Government should have the same open mind.”

Editor’s note: For on-the-scene pictures and video during the April 14 March for Science in Washington, D.C., follow @sciencenewsmagazine on Instagram.