Radioactive cigarettes

Burning tobacco unleashes hundreds of chemicals, many of which may play a role in lung cancer. Below the radar screen of most environmental scientists and physicians, however, is the radioactive contamination of tobacco with polonium-210. The April issue of the Health Physics Society newsletter crossed my desk today with a four-page feature on this pollutant in cigarettes. I was familiar with the issue generally, having written about it 27 years ago. What I wasn’t aware of until reading this new piece by health physicists Dade Moeller and Casper Sun was that “a filter for removing it [polonium-210] from cigarette smoke has been available for more than 40 years.”

It is not, of course, employed by cigarette manufacturers.

First some disturbing stats from the article:

— recent studies have shown a synergy between polonium and carcinogenic chemicals in cigarette smoke that increase the lifetime risk of lung cancer 8- to 25-fold

— Americans collectively receive annual radiation exposures from cigarette smoke equal to half of the total dose to the entire U.S. population from diagnostic medical X-rays (the article contains calculations to justify this claim).

The source of tobacco’s polonium is all natural. It’s a decay product of radon that escapes from the ground, especially in regions with a lot of bedrock close to the surface or soil containing uranium-238. (On average, the authors say, the top five feet in each square mile of soil contains some 30 tons of uranium-238.)

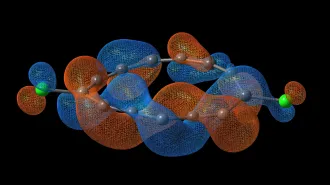

Radon decays through a chain of up to seven steps — morphing through up to seven radionuclides — eventually becoming polonium-210. This polonium is electrically charged and will adhere to anything with the opposite charge, such as tobacco leaves. Fostering tobacco’s accumulation of this isotope is the fact that its leaves are covered with tiny hairs (trichome is the formal name) that exude a sticky substance that essentially glues polonium particles in place. As the tobacco leaves are cured and processed, Moeller and Sun note, the polonium becomes a part of the cigarettes. Lighting up will volatilize this radioactive material, allowing smokers to inhale it deeply into their lungs.

The article goes on to calculate the typical dose of polonium likely to reach the lungs from years of exposure to cigarette smoke — including secondhand smoke.

Conclude the authors: “It is far beyond time that polonium be removed from cigarettes and/or cigarette smoke.”