After 2,000 years, Ptolemy’s war elephants are revealed

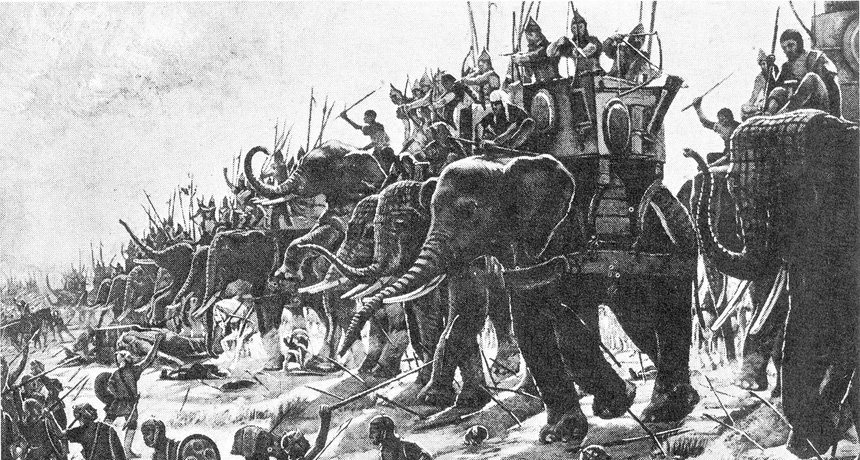

Carthaginians used war elephants against the Romans in the Battle of Zoma in 202 B.C., as seen in this 1890 painting by Henri-Paul Motte. A new genetic study sheds light on world’s only known battle between Asian and African war elephants in 217 B.C.

Painting by Henri-Paul Motte, reprinted in Das Wissen des 20. Jahrhunderts (1930)/Wikimedia Commons

If you think back to history class, you might remember the tale of Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps in 218 B.C. to sneak up on Rome during the Punic Wars. It was notable not just because he brought an entire army from Carthage to Rome the long way around, but because that army included elephants.

The use of war elephants dates back at least to the fourth century B.C., when Indian kings took Asian elephants into battle. The practice soon spread west to the Persian Empire and then northern Africa, where African elephants were put to military use. There’s only one known case, though, of an African elephant-Asian elephant matchup, at the Battle of Raphia near Gaza on June 22, 217 B.C. The battle, over the sovereignty of Syria, matched the forces of Ptolemy IV, pharaoh of Egypt, against those of Antiochus III, a Greek king whose reign stretched into western Asia.

Ptolemy won the battle — but not because his elephants were any help, at least according to Greek historian Polybius, who described the encounter in his work The Histories:

A few only of Ptolemy’s elephants ventured to close with those of the enemy, and now the men in the towers on the back of these beasts made a gallant fight of it, striking with their pikes at close quarters and wounding each other, while the elephants themselves fought still better, putting forth their whole strength and meeting forehead to forehead. The way in which these animals fight is as follows. With their tusks firmly interlocked they shove with all their might, each trying to force the other to give ground, until the one who proves strongest pushes aside the other’s trunk, and then, when he has once made him turn and has him in the flank, he gores him with his tusks as a bull does with his horns. Most of Ptolemy’s elephants, however, declined the combat, as is the habit of African elephants; for unable to stand the smell and the trumpeting of the Indian elephants, and terrified, I suppose, also by their great size and strength, they at once turn tail and take to flight before they get near them.

This account stumped later historians and naturalists. African elephants tend to be larger than Asian elephants, so what was up with Ptolemy’s elephant soldiers?

One possibility is that Ptolemy’s elephants belonged to an extinct subspecies. Another, proposed by classical scholar Sir William Gowers in 1948, holds that Ptolemy fought with smaller forest elephants (African elephants are actually two species — forest and savanna). That idea has persisted for decades.

The answer, however, lies in where Ptolemy was sourcing his war elephants.

The natural range for African elephants does not stretch into present-day Egypt. To get elephants, Ptolemy’s army looked to what is now Eritrea. Today, elephants in Eritrea are rare, numbering only 100 to 120. The population lives near the border with Ethiopia, sometimes migrating into that country. When Adam Brandt of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and colleagues conducted a genetic study of those elephants — by sequencing DNA in elephant poo — they found that Eritrea’s elephants are not forest elephants; they’re savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) with no genetic ties to either the forest or Asian species.

“Most likely, the Greek historian who wrote about the battle added in his own interpretation as to the relative size of the elephants,” study coauthor Alfred Roca of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, wrote in an email. “There were semi-mythological accounts in the ancient world that attributed great size to the elephants of India, and these were probably known to Polybius, and were likely the source of his belief that Indian elephants were the largest of all.”

The Eritrean elephant population shows signs of inbreeding and isolation, the researchers report in the January-February Journal of Heredity. That’s not surprising because the population is small, and its nearest elephant neighbors are more than 400 kilometers away.

Being a small, isolated population is generally not good for survival, but Eritrea’s elephants are getting a helping hand from that nation’s agriculture ministry. The ministry is trying to minimize conflict between humans and elephants, and they’ve seen some success: The range and size of the population appears to be increasing. If these elephants need a bit of a genetic boost, though, the researchers note that their study has identified Eastern Africa savanna elephants as the population with the closest genetic affinity to the Eritrean population and best suited for any future breeding or transplantation projects.