Birds large and small hop over obstacles in similar ways

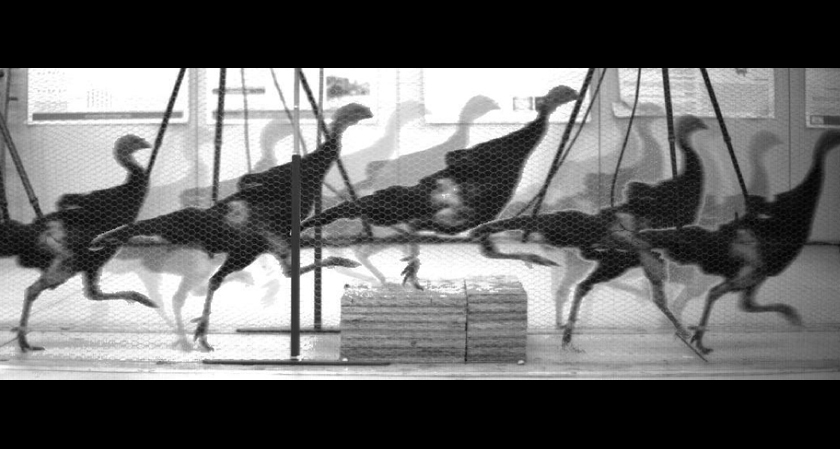

A turkey moves over a step with a strategy similar to the one used by tiny quail and huge ostriches.

Oregon State Univ.

A tiny quail and a huge ostrich would seem to have little in common given their 500-fold difference in size. But when faced with an obstacle in their path, the birds tackle it in the same way, scientists report October 29 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Aleksandra Birn-Jeffery of the Royal Veterinary College in Hatfield, England, and colleagues wanted to know how running birds negotiate a step. How two-legged creatures navigate obstacles can be helpful for inventors hoping to create two-legged robots, but it seems that humans may not be the best models. Though our ancestors started walking upright millions of years ago, birds have been doing it for far longer — bipedal locomotion can be traced back 230 million years to theropod dinosaurs.

So the researchers brought five species of birds into the lab: quail, pheasant, guinea fowl, North American turkey and ostrich. Because ostriches are capable of killing people (a common trait among many large flightless birds), Birn-Jeffery hand-raised the birds for two years so they could be safely handled. Members of the other species had their wings clipped so that they wouldn’t fly away.

All the birds tackled the step in a similar way — in three steps, with an initial vault onto the step and slightly crouching while on top of it — regardless of size. This was surprising because the large ostrich runs differently than the smaller birds. The ostrich uses straighter legs to minimize stress on muscles and bones, while the smaller species tend to crouch, which allows for smooth body motion over uneven terrain. But when faced with a step, all the birds used a strategy that coupled energy efficiency with leg safety.

“In the wild, injuries can result in predation, and food energy resources are often limited, thus, injury avoidance and economy are likely to be important factors in fitness,” the researchers note.

The motion isn’t always smooth and sleek, though. The birds avoid falling and injuring themselves, but their upper bodies may bounce around.

The similarities between species may break down, however, with obstacles of a different size or type, Birn-Jeffery says. “A large bird, such as an ostrich, would not be able to successfully negotiate an 80-percent-leg-length obstacle using this strategy,” she says. “They would more than likely have to slow down before encountering the obstacle, something which none of our birds in the current study did.” A quail, though, might not have to change its strategy to tackle a higher height.

Coauthor Monica Daley, also at the Royal Veterinary College, is currently investigating whether the birds’ strategies change with other types of terrain. The research may help scientists create stable, running robots.

Bipedal, ground-running birds come in a variety of sizes, from tiny quail to huge ostriches. But when presented with a short step, they all tackle the obstacle in a similar way: an initial vault up, slightly crouching on top and a third step back down to the ground.

Credit: A.V. Birn-Jeffery et al/Journal of Experimental Biology 2014