From the April 2, 1938, issue

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BELIEVE IT

Another traveler is recounting the wonders of his latest expedition into the hypothetical wilds, equipped with a good imagination and plenty of snakebite medicine. Today, we smile indulgently at these traveler’s tales, but not so long ago, each and every yarn was carefully remembered, and passed on (sometimes “improved” a little) to the next avidly listening ear.

Perhaps the “tall story” is a racial heritage of the days when there was no writing, and wandering minstrels were our newspapers and sources of information. Primitive tribes still retain their histories as legends, passed on by word of mouth from father to son.

Today, however, the “tall story” is a part of our literature. Newspapers run “whopper columns, paying a rather good price for each new tall tale. Several hunting and fishing magazines publish the wildest possible stories sent in by their readers, and the doings of such legendary characters as Paul Bunyan and Juan Catorce are the subject of Ph.D. theses and massive tomes.

Guides in the wilder parts of the country still collect and tell wild tales of wilderness and mountain country to the “dudes,” “palefaces,” and “flatlanders” who each year leave their inhibitions and intellects in the city and spend two glorious vacation weeks collecting sunburn, poison ivy and mountain sickness.

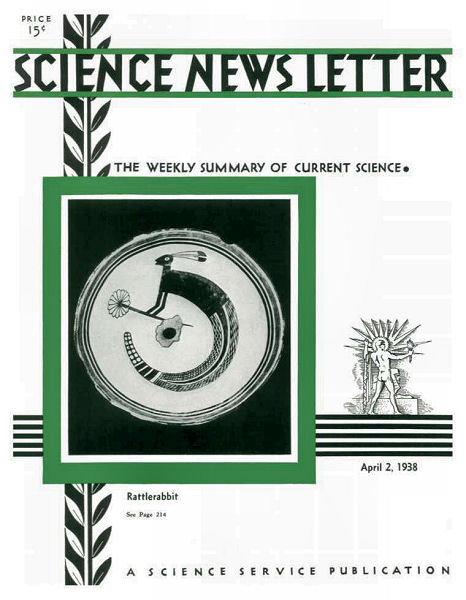

Surrealism seems to be related psychologically to the “tall tale.” Mimbres Valley people of 1,000 years ago suffered from that, too. On one of their bowls (pictured on the front cover) is painted a perfect “rattlerabbit,” whose body to the waist is that of a rabbit, but whose tail belongs to a rattlesnake.

Every old map is shown complete with a galleon sailing on the ocean, and a sea monster lying in wait for luckless seamen. We laugh at this naïve belief, but not long ago a group of scientists spent considerable money investigating the Loch Ness monster reported from Scotland. Even today, a request for funds to be used in a hunt for dinosaurs in South America, or ice worms in Alaska, will bring a response, sometimes sufficient to enable a doughty warrior to drink himself into a happy stupor, in which he can dream about the strange animals without leaving the safety of his favorite bar.

VOLCANO UNDER GLACIER GIVES OFF FLUORINE

Fluorine gas, super-corrosive vapor that dissolves even glass, given off in quantities by Iceland’s subglacial volcano, sickens sheep and humans in its vicinity, reports Dr. H. Vigneron (La-Nature .) Lesions of the membranes of the nose and mouth are caused by the gases, he states.

Acting like a giant calorimeter, or device for measuring the heat given off by a fire, Vatnajokull, the crater under the ice, supplies geologists with a rather accurate measure of the energy of a volcanic eruption. From the amount of ice melted away from the Icelandic glacier, they can tell quite closely the amount of heat give out by the volcano. To date, this eruption has melted several cubic miles of ice. Now, it is becoming quiescent, but another eruption is expected in about 1945-50, judging from the past behavior of the crater.

VIRUSES, DECLARED NON-LIVING, SHOW SOME SIGNS OF LIFE

Submicroscopic particles of proteins that cause the virus diseases of plants and animals are again the subject of discussion: are they alive or not?

For a long time they were considered to be “living molecules.” Then they were assigned to the non-living realm, especially as the result of researches in the last couple of years at the Rockefeller Institute laboratories at Princeton, N.J.

Now, Drs. T.E. Rawlins and William N. Takahashi of the University of California indicate several points in which these elusive filter-passing substances persist in acting as though they were alive (Science, March 18).

One suggestion that they may be living is found in the way they refract or bend light. A similar refraction is produced by living substance in the heads of sperms or male sex cells—which are undoubtedly living objects.

Another point is raised over the chemical nature of the viruses. They are now commonly considered to be enzymes, yet they consist of nucleoproteins. Nucleoproteins are proteins found characteristically in the nuclei of living cells, and not in ordinary enzymes.

Drs. Rawlins and Takahashi also call attention to the enormous molecular weights of the virus proteins. These are figured in the millions, very much higher than the molecular weights of known enzymes. They suggest therefore that instead of being single molecules the virus particles may be aggregates of molecules—another hint that they may be alive after all.

Drs. Rawlins and Takahashi avoid categorical declarations. They state:

“It is obvious that much of the above speculation is based on meager evidence; it is presented with the hope that it may stimulate further research in this field rather than that it may enable the reader to reach a conclusion regarding the nature of viruses.”