‘Aroused’ recounts the fascinating history of hormones

A new book explores the story of the chemicals that put the zing into life

HORMONE HISTORY Neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing did pioneering work on the hormone-producing pituitary glands in the early 20th century, as described in a new book. Samples of the brains he studied are now displayed in the Yale medical school library.

techbint/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Aroused

Aroused

Randi Hutter Epstein

W.W. Norton & Co., $26.95

The first scientific experiment on hormones took an approach that sounds unscientific: lopping off roosters’ testicles. It was 1848, and Dr. Arnold Berthold castrated two of his backyard roosters. The cocks’ red combs faded and shrank, and the birds stopped chasing hens.

Then things got really weird. The doctor castrated two more roosters and implanted a testicle from each into the other’s abdomen. As Randi Hutter Epstein writes in a new book, each rooster “had nothing between his drumsticks but a lone testicle in his gut — yet he turned back into a full-fledged hen-chaser, red comb and all.” It was the first glimpse that certain body parts must produce internal secretions, as hormones were first known, and that these substances — and not just nerves — were important to the body’s control systems.

Today, we know that hormones are chemical messengers shaping everything from sex and development to sleep, stress, mood, metabolism and behavior. Yet few of us know much about these powerful substances coursing through our bodies. That ignorance makes Aroused — titled for the Greek meaning of the word hormone — an invaluable guide.

Epstein, a medical writer and M.D., tells the history of hormone research from that first rooster experiment, but cleverly moves back and forth through time, avoiding any hint of dry recitation. She explores the scientists who discovered and deciphered the effects of important hormones, as well as the personal stories of how people’s lives have been profoundly changed by these chemicals.

There’s Barbara Balaban, who launched a nationwide campaign to collect pituitary glands from cadavers’ brains to extract growth hormone for her short-statured son. Readers also meet Bo Laurent, born intersex, as well as Nate Snizek, whose rare endocrine disorder makes him insatiably ravenous.

And among the scientific heroes profiled is Rosalyn Yalow, who developed the radioimmunoassay that makes measuring hormones and treating imbalances possible — a feat that earned her a Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1977 (SN: 10/22/77, p. 260).

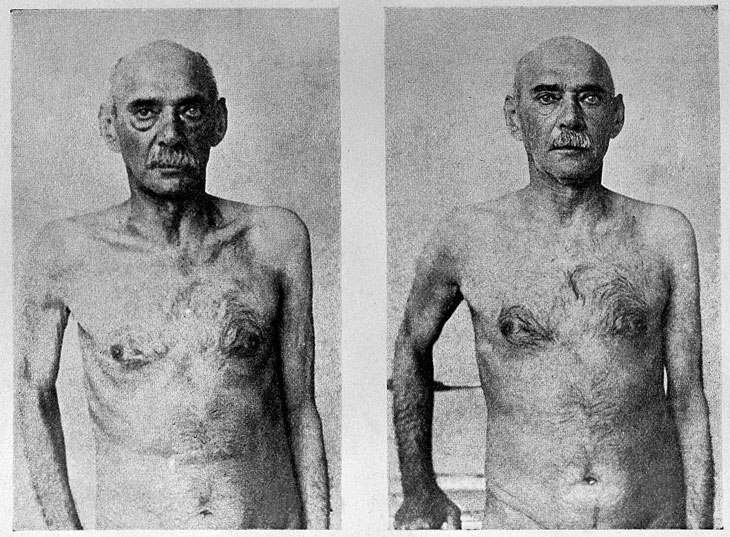

One striking lesson from the book is that we have, over and over again, tried to use hormones to our advantage before really understanding how they work. The hormone from testicles wasn’t isolated and named testosterone until 1935. But by the 1920s, men already were looking for ways to get more of this unknown essence of virility.

The Viennese physiologist Eugen Steinach believed that getting a vasectomy would boost the substance in men (it doesn’t), and Sigmund Freud and William Butler Yeats were among the many men “Steinached” in an effort to restore youthful vim and vigor.

One of the latest hormones to be ballyhooed is oxytocin, which is involved in maternal-child bonding and other social behaviors. Since a 2005 study linked it to trust (SN: 6/4/05, p. 356), the hormone has been billed as the “moral molecule.” You could even buy a spritzer of so-called “liquid trust.” As Epstein details, many of those promises hinge more on hope than science.

Even testosterone has made a commercial comeback. Rebranded as “low-T” therapy, testosterone injection is a booming business. Once again, aging men are lining up before testosterone therapy’s risks and benefits are made clear (SN: 4/1/17, p. 8).

In the end, Epstein paints a portrait of how hormones control us and how we yearn to control them. Perhaps appropriately, it’s a history marked by our shifting moods.

Buy Aroused from Amazon.com. Science News is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. Please see our FAQ for more details.