When winter comes, many people vacation in the Caribbean. A new report suggests basking sharks have the same idea.

Using satellite-based tagging technology, scientists have figured out that basking sharks migrate to the tropical waters of the Caribbean when the weather in their temperate locales gets cold. The study, published online May 7 in Current Biology, provides the first information on where basking sharks hide out for winter, a mystery that has flummoxed marine biologists for years.

Basking sharks, the second largest fish, are commonly seen in temperate regions of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Previous studies showed that basking sharks in the North Atlantic feed on plankton off the coast of New England during the late spring, summer and early fall.

Until now, scientists thought basking sharks were limited to temperate regions. The 6-to-7-meter sharks disappear from view in the wintertime, but some researchers had suggested that the sharks hibernate on the ocean floor.

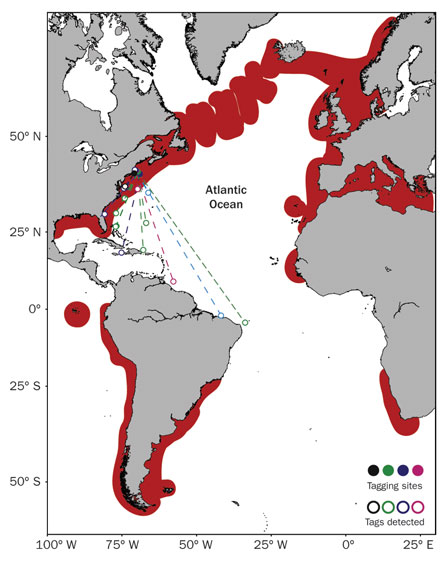

In the new research, Gregory Skomal of the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries’ Martha’s Vineyard research station and his colleagues tagged 25 basking sharks off the coast of Cape Cod and tracked them as they made their wintertime trip. The researchers found that the sharks headed south, some going as far as Brazil.

“This is definitely an important contribution,” comments marine biologist Robert Hueter of Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Fla.

Each shark was tagged with a unit that recorded water temperature, ambient light and pressure. The tags were programmed to fall off the shark at points throughout the winter and pop up to the surface of the ocean to transmit the data via satellite.

Although basking sharks usually swim near the ocean surface in the spring and summer, the sharks made their winter journeys at depths of 200 to 1,000 meters and stayed at those depths for weeks or months at a time. This is probably why no one spotted the sharks at their winter location, Skomal says.

Why basking sharks make the trip is still a mystery. The waters off the coast of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida would provide similar temperatures as the tropics and ample plankton for food, the researchers say. “Energetically, it doesn’t make sense to swim so far south,” Skomal says.

One theory is that basking sharks travel south to mate and give birth. “No one knows where basking sharks go to give birth. We’ve never seen a pregnant female, and never seen a baby basking shark,” Skomal says. The tropics could provide a good shark nursery location because of stable water temperatures and few predators, the scientists say.

“This is a good analysis and a likely explanation for the data,” Hueter says.

Numbers of basking sharks worldwide are dwindling, and the new information could alter population estimates, the researchers say. “Now that we know that the sharks move these distances, physical barriers between populations simply don’t exist,” Skomal says. “Different populations could actually be connected between regions and even between oceans.”