Bronze Age humans racked up travel miles

Large-scale genetic study also shows that many of these ancient peoples were lactose intolerant

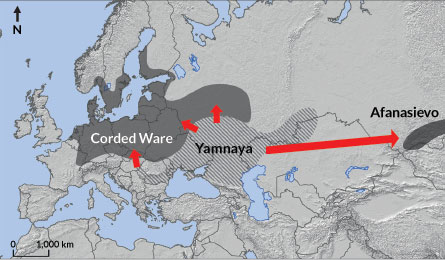

PAST JOURNEYS This ocher-covered skull, found in southwestern Russia, comes from a member of the Bronze Age’s Yamnaya culture. A new genetic study reveals that this culture spread far and wide across Eurasia.

Natalia Shishlina