Bees apparently have their own version of Starbucks and may even get hooked on the joe: Honeybees are more likely to remember a flower that laces its nectar with a hit of caffeine, a new study shows.

“This is the first instance to show that something we use as a drug is also a drug ecologically,” says study leader Geraldine Wright, a specialist in the neuroscience of animal behavior at Newcastle University in England. Experiments probing the effects of caffeine on the bees’ brains suggest the drug strengthens brain reward circuitry, Wright and her colleagues report in the March 8 Science.

Many plants have bitter compounds in their leaves — caffeine itself or opiates, for example — that may deter animals from eating them. And it’s fairly common for the compounds to also show up in nectar, even though the plant nectar is all about attraction, not deterrence. “It’s very paradoxical and surprisingly common” says pollination biologist Rebecca Irwin of Dartmouth College.

For the new study, Wright and her colleagues began by measuring the amount of caffeine found naturally in the flower nectar of four species of citrus plants and three species of coffee. The flowers of tangerine and sweet orange had the lowest concentration, while the flowers of Coffea canephora contained roughly the same concentration as a cup of instant coffee. Then the researchers trained honeybees, Pavlov-style, to associate a floral scent with a sugary cocktail laced with caffeine in amounts that reflect the ranges found naturally in nectar.

That caffeine provided an edge, boosting the bees’ long-term memory, the researchers discovered. Compared with bees trained on sugar water alone, bees trained on sugar water doped with caffeine were three times as likely to remember 24 hours later that the floral scent came with a reward. After 72 hours, the caffeine-trained bees were twice as likely to remember the scent-reward connection.

The caffeine concentration in the nectar is impressive, Irwin says. The quantities in the tested coffee plants and citrus suggest that evolution may have fine-tuned the nectar recipes. The caffeine levels never crossed the bees’ too-bitter threshold, Wright found; the amounts probably make bees into return customers. A pollinator that better remembers a flower may be a more loyal client, improving the chance that the plant will get visited by an insect bearing pollen from the same species of plant.

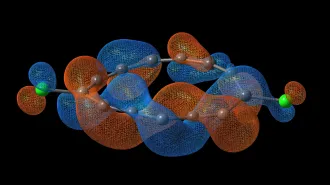

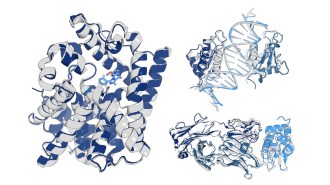

Wright and her colleagues also examined how the brains of bees respond to caffeine. Removing the bees’ tiny brains and washing them in a caffeine-saline bath revealed that the caffeine excites cells implicated in reward and long-term memory.

While there’s no evidence yet that bees get the shakes from an overdose, Wright is exploring whether bees may get addicted to caffeine.