The frenetic scurrying of ants around a nest may seem like much ado about nothing. There’s method in their madness, however.

All this activity adds up to ingenious strategies for collectively working out the shortest path to a food source, combining forces to move a large, unwieldy object, and performing other functions crucial to an ant colony’s well-being.

Certain ant species send out foragers along more or less random paths to explore a nest’s surroundings. Each scout lays down a trail of scent molecules, or pheromones. When one of them finds food, it returns to the colony to pass along the news to others, who can then follow the scent trail.

An ant taking a shorter path to a particular food source returns sooner from its round-trip excursion than a second one following a longer trail. Other ants start on the shorter path, reinforcing its odor cue, before the second ant returns from the lengthier route. The stronger its scent, the more ants choose a given path. So, the longer route gets less traffic, and its scent slowly fades away as the pheromone evaporates.

In effect, astonishing feats of teamwork emerge from a large number of unsupervised individuals following a few simple rules. This sort of self-organizing cooperative behavior among ants, bees, and other social insects has become the envy of engineers and computer scientists as they work to solve tough path-finding, scheduling, and control problems in industrial and other settings.

In recent years, studies of ant behavior have suggested powerful computational methods for finding alternative traffic routes over congested telephone lines and novel algorithms for governing how robots operating independently would work together.

In the July 6 Nature, engineer and biologist Eric Bonabeau of EuroBios in Paris and the Santa Fe (N.M.) Institute and his colleagues argued that this new line of research transforms knowledge about social insects’ collective behavior into new problem-solving techniques, which the researchers term “swarm intelligence.”

“These techniques are being applied successfully to a variety of scientific and engineering problems,” the researchers contend.

They’re not the only ones who think so. In September, an assortment of biologists, ecologists, computer scientists, and engineers came together in Europe to compare notes on insect behavior and algorithm development at three meetings with intriguing titles: the Sixth International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature and the Sixth International Conference on the Simulation of Adaptive Behavior, both in Paris, and the Second International Workshop on Ant Algorithms (ANTS 2000) in Brussels.

Stringent test

The classic traveling-salesman problem has long served as a stringent test of methods designed to solve difficult computational puzzles. The task consists of finding the shortest route that takes a traveler just once to each of a given number of cities before returning home.

Obtaining the shortest route requires trying all the possible combinations of city-to-city connections. When the number of cities is large, this would take a prohibitively long time. There are billions of route possibilities among just 15 cities.

In practical situations, however, engineers and others usually settle for a good answer, instead of the best one. Ant foraging behavior suggests a shortcut for getting an acceptable answer.

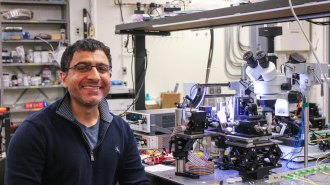

Computer scientist Marco Dorigo of the Free University of Brussels in Belgium and his coworkers have devised a path-optimization method that mimics in software the pheromone-trail building of an ant swarm.

In this instance of virtual sales trips across a digital landscape, each artificial ant, or agent, hops from point to point on an electronic map, favoring nearby points but otherwise traveling randomly. After it completes its sales tour, the agent goes back to each hop and deposits the digital equivalent of a pheromone on that segment. The amount of pheromone depends on the tour’s length—the shorter the total distance, the more pheromone each of the segments receives.

After all the artificial ants have completed their tours and spread their scent, the software pools their results. Point-to-point links that belong to the largest number of short tours become richest in pheromone. The swarm is then released again. This time, however, the agents favor both the nearby links and those with higher faux pheromone concentrations.

Dorigo and his collaborators found that while repeating the routine hundreds of times, artificial ants follow progressively shorter routes.

Permitting artificial pheromone to evaporate at a steady rate proved to be the key to avoiding a mediocre solution. The evaporation kept the colony from getting stuck with a link that happened to be part of many routes but was not a component of a suitably short tour.

Interestingly, the researchers had to adopt a pheromone evaporation rate much higher than that found naturally among ants to obtain an acceptable answer within a reasonable period.

You typically start with models of ants behavior, then add things that are not present in the real world, Dorigo says.

Ant algorithms

More sophisticated versions of the method, known as ant-colony optimization, include such refinements as local searches that check several nearby sites to see which one works best. These improved ant algorithms are competitive with other state-of-the-art approaches to the traveling salesman problem, Dorigo says.

Variants of the same technique can also be applied to other optimization problems, such as finding vehicle routes. Just such an algorithm is already in use in Switzerland for routing gasoline trucks, and one company, Unilever, is considering another version of the algorithm to schedule production at a large chemical plant.

Computations based on ant-colony optimization don’t always work well, Dorigo admits. For example, when cities in the traveling-salesman problem are truly randomly distributed, the method generally fails to zero in quickly on an acceptably short route. Luckily, many real-world problems possess enough of a pattern for the technique to be efficient, Dorigo says.

A similar approach, called ant-colony routing, can help switching stations pass packets of information efficiently across telecommunications networks (SN: 1/2/99, p. 12: http://www.sciencenews.org/pages/sn_arc99/1_2_99/bob2.htm). Antlike agents wander a network and report where they experience delays and for how long. With that information, the software then updates switching-station routing tables to improve the network’s performance.

Developed by Ruud Schoonderwoerd of the Hewlett-Packard Laboratories in Bristol, England, and his colleagues, the technique enables a network’s switching stations to respond quickly to congestion, local breakdowns, and other network problems.

Unpredictable environments

The foraging behavior of ants also provides lessons for robotics engineers who want to create independent, mobile robots that operate effectively in unpredictable environments.

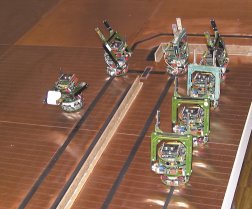

Ecologist Laurent Keller of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and his coworkers have applied experimental data on the division of labor among real-life ants to orchestrate the behavior of a swarm of small robots. The researchers describe their approach in the Aug. 31 Nature.

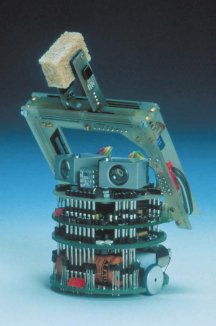

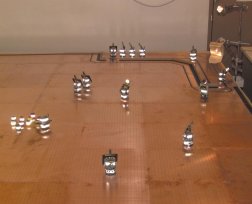

In their experiments, the team used up to 12 miniature, mobile Khepera robots, developed at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. Just 55 millimeters in diameter, each robot was programmed to roam a 9-square-meter area to search for tokens representing food and bring them back to a base station, the equivalent of a nest.

The researchers tracked the swarm’s overall energy level—a numerical measure that reflects the amount of energy expended by robots looking for food versus the amount added to the colony’s energy reserves by the food retrieved. Radio messages informed individual robots at the nest of the colony’s overall energy status. When energy dropped below a certain threshold, one or more robots would leave the nest to forage.

Keller and his coworkers programmed the robots to avoid colliding with each other. They also introduced individual differences among the robots by varying the energy thresholds that would trigger action.

The investigators found that, in general, groups of robots foraged more efficiently and maintained higher levels of total energy than any single robot did. However, as the groups included more than three or so robots, the benefits of group living decreased, possibly because the robots would slow each other down during foraging.

Other scientists have documented a similar relationship between group size and efficiency in social insects, Keller says. Real-life ants and wasps, for example, tend to have foraging parties that do not exceed a certain size.

In some of the robotic experiments, one robot could enlist another if it happened to identify a resource-rich area. This recruitment made the group’s overall foraging effort more efficient.

“Our results show that an ant-inspired system of task allocation…provides a simple, robust, and efficient way to regulate activity within teams of robots,” the Swiss team concludes. “This has important implications in robotics, particularly in situations where risk of system failure must be avoided, for example during missions on Mars and other planets.”

Stimulating research

Ant colonies have stimulated many other researchers whose interests include controlling crowds, designing office buildings, sorting data, and pushing large boxes.

Consider ants’ remarkable cooperation in moving large, heavy objects up steep slopes. Whereas human movers tackling a bulky object might talk to each other during the task, ants typically “communicate” with cues delivered through the object itself, says Bonabeau. Each ant senses imbalances in forces directed at the object by other ants and automatically shifts to reinforce the weak side. The same idea could be applied to robots designed to move bulky containers.

In the ant species Leptothorax unifasciatus, researchers have observed that the eggs and the tiniest larvae are in the center of the brood area and progressively larger larvae are farther out. Worker ants seem to expend considerable effort sorting and consolidating the brood.

Biologists have proposed that an ant picks up and drops an item according to the number of similar items nearby. If an ant is carrying a large larva, it’s more likely to drop it off among large larvae. If an unladen ant happens upon a large larva surrounded by eggs, it will zero in on the larva and move it away.

Although this model for ant behavior has yet to be validated, computer scientists already have found it useful for data sorting, where artificial ants perform random walks to pick up or drop off data items according to criteria of similarity.

“We have no doubt that more applications of swarm intelligence will continue to emerge,” Bonabeau and his colleagues insist. “In a world where a chip will soon be embedded into every object, from envelopes to trash cans to heads of lettuce, control algorithms will have to be invented to let all these ‘dumb’ pieces of silicon communicate.”

Moreover, as models of swarm intelligence become more commonplace in the world of computation and control engineering, there may be some payback for the biologists who have helped uncover the basic rules. Models from the realms of computation and robotics could provide new insights into the behavior of social insects.