Cave art suggests Neandertals were ancient humans’ mental equals

Newly dated rock drawings and shell ornaments predate Homo sapiens in Europe by at least 20,000 years

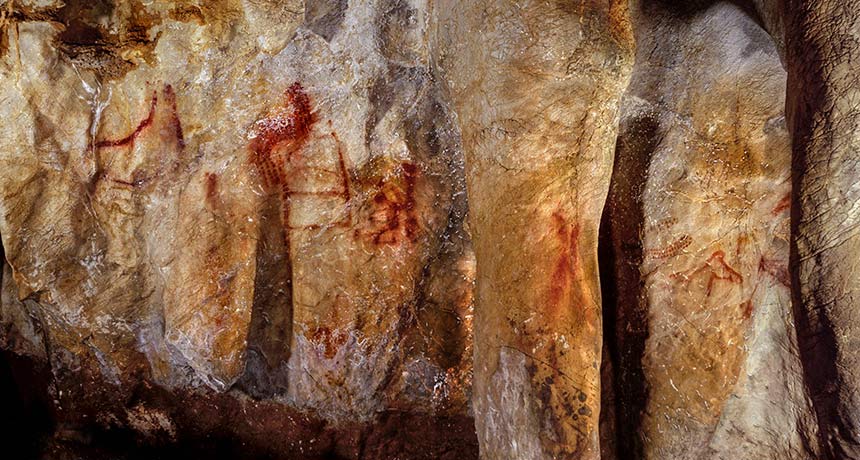

ARTISTIC SURPRISE Red horizontal and vertical lines painted on the walls of a Spanish cave date to at least 64,800 years ago, a new study finds. Since Homo sapiens had not reached Europe at that time, Neandertals must have created this art, researchers propose. The animal-shaped figure, right, was not dated and its makers remain unknown.

© P. Saura