Can scientists make fruits and veggies resilient to climate change?

It takes many years to produce new cultivars, but genomics tools are streamlining the process

To protect our fruits and veggies from climate change, scientists are developing new methods for cultivating plants.

Oliver Rossi/DigitalVision/Getty Images Plus

In 2023, a new type of apple made its commercial debut at a trade show in Berlin. The Tutti is crisp, juicy and has that perfect blush tinge — a lovely cultivar that took decades to produce. But it has a bigger claim to fame: It is designed to thrive at temperatures as high as 40° Celsius (104° Fahrenheit).

The apple is a product of the Hot Climate Partnership, a collaboration between researchers and industry groups in Spain and New Zealand to create crops capable of thriving in ever-warmer climates. The group teamed up in 2002 in the midst of increasingly hot summers in the Catalan region of Spain that left apples grown there sunburned and mushy. After more than 20 years of crossbreeding for heat tolerance, the Tutti (whose research name is HOT84A1) was unveiled.

Now being grown as far afield as the United States, Chile and China, the Tutti joins a growing list of fruits and vegetables that researchers are trying to climate-proof as Earth heats up. Using tools ranging from the old-fashioned — crossbreeding, reviving Indigenous plants, heat-conscious planting techniques — to the new, such as gene editing, researchers are trying to help plant breeders and backyard gardeners alike stay one step ahead of the changing planet.

It’s a tall task. What felt hot 20 years ago is now commonplace, says Joan Bonany, a pomologist at the Institute of Agrifood Research and Technology outside Barcelona who helped form the Hot Climate Partnership. Memories of being able to comfortably walk between his tidy rows of apple and pear trees “stretch further and further back in time,” he says, and preempting the future “is very much like shooting a moving target.”

In some ways, Bonany says, the Tutti is already outdated.

“Temperatures above 40° Celsius, which are increasingly baked into our future, are going to create some real issues,” says Mario Andrade, a plant geneticist at the University of Maine in Orono and coinvestigator on a project to create climate resilient potatoes.

What happens to crops as temperatures rise?

To hit that moving target, scientists are starting with what they know about how plants handle heat.

Research has shown that even a slight bump in temperatures during cropping season can significantly weaken the yield of many plants. For instance, globally, every 1 degree C increase amounts to a 10 percent and 6.4 percent loss in rice and wheat yields, respectively — foods that along with corn account for the majority of the world’s food calories.

But that’s only one of many things that can go awry when temperatures climb. Other signs of heat stress that you might commonly see in your own garden plants include drooping, slower growth, signs of burning on leaves and stems, smaller fruits and vegetables, or plants that flower but never produce crops at all — a sign that their pollen, which is sensitive to heat, has been damaged. Some plants even signal their distress audibly, making tiny ultrasonic clicks when they get really thirsty (SN: 3/30/23).

As temperatures continue to rise, the very proteins that perform a plant’s essential functions, such as directing photosynthesis, shuttling water and nutrients, and warding off disease, begin to unfold and disintegrate, says Owen Atkin, a plant scientist at the Australian National University in Canberra who develops heat-tolerant wheat. Plants can repair this damage using quick-acting heat shot proteins. And past 50° C (122° F), plants can begin to change the chemical composition of their cell membranes to keep their lipids from melting like butter left on the counter. But they do so at a cost.

“The cost of living as you try to repair, repair, repair, because degradation is getting faster, means that you’re spending a lot more energy on surviving,” Atkin says. “We’re going to need some breakthrough work to protect against that kind of damage.”

Putting the freeze on warming

Most new plant varieties today are still made as they have been for thousands of years, through a process known as selective breeding in which parents with desirable traits are crossed, and their progeny winnowed down over successive generations until only the most robust remain. It’s a lengthy process, and there aren’t many ways to shorten it — “A plant grows as fast as a plant grows,” Andrade says — but there are new ways of making the process more efficient.

One of the most pressing challenges is the fact that researchers and breeders must balance conflicting needs. A plant that is heat tolerant but susceptible to disease won’t sell, nor will one that is disease resistant but produces low-quality fruit. Each of these traits may be controlled by hundreds of genes, all of which interact in unexpected ways. It’s a data nightmare that makes studying the genetic basis for different traits a challenge.

Now though, the ability to screen a plant’s entire genetic code has launched a new era of genome-assisted breeding, in which scientists still make crosses, but leverage modern tools to guide their choices. For example, scientists can now compare the genetic makeup of different cultivars to probe which quirks of their DNA may give one strain greater heat tolerance than another. That also negates the need to wait for each generation to grow large enough to demonstrate a trait. Researchers can now quickly look at a cultivar’s genetic code to identify if a cross has a desired gene and narrow their list of likely contenders.

It’s only by knowing the exact genes driving a trait that breeders can begin to manipulate them, says Rajeev Varshney, the director of the Center for Crop and Food Innovation at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia. This manipulation can involve genetic modification, in which a gene from one species is added into another, or gene-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9 that allow scientists to tweak small snippets of a plant’s code — changes that have produced climate-friendly strawberries, tomatoes and potatoes.

Shifting zones

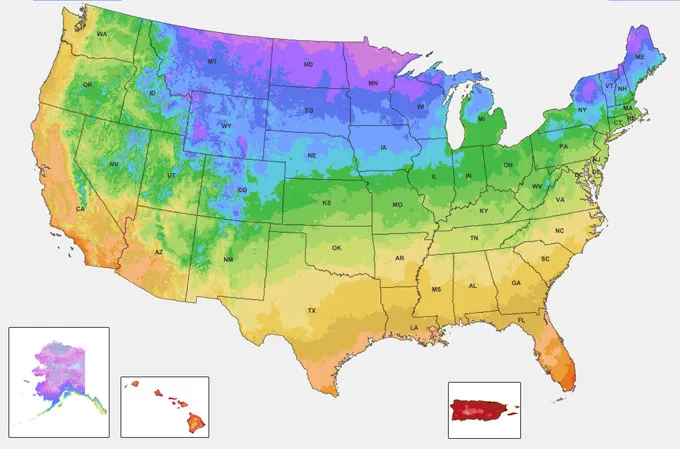

The year 2023 brought record-breaking temperatures to important agricultural centers worldwide, and even backyard gardeners are having to rethink their strategies. In the United States, the Department of Agriculture released a new plant hardiness zone map — used by commercial growers and gardeners alike to determine which plants are likely to flourish in a particular region — in acknowledgement of the fact that winter low temperatures are now 2.8 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer on average than in the past. Colder (blue) and warmer (red) colors represent colder and warmer minimum winter temperatures.

In one study, researchers identified a gene called AtGRXS17 in Arabidopsis, a small plant from the mustard family that is widely used in research, that appeared to be involved in drought tolerance. When they added the gene into tomatoes and withheld water for 10 days, the modified plants retained their vigor and produced fruit, while plants without the gene did not. In another, using CRISPR/Cas9 to modify a single gene called FaPG1 produced firmer strawberries that were more water retentive.

For the moment, leveraging these cutting-edge tools remains costly, and so it’s most often private companies developing them for large-scale operations. As such, most edited crops are out of reach for the average gardener for now. The first cultivar marketed directly to home gardeners was only recently released, in February 2024 — a deeply purple tomato that gets its hue thanks to a few genes purloined from snapdragon flowers.

But Varshney notes that costs are dipping all the time, and it’s likely that we’ll soon see more options available to consumers. “In the coming years, discoveries are going to come much faster,” he says. “I feel very optimistic that we will have many more heat-tolerant and drought-tolerant plants.”

Can we use any past techniques for future crops?

It is possible to buy traditionally bred seeds from commercial companies that are marketed as being “heat tolerant” — meaning that they grow relatively well under hot conditions compared with non-adapted strains. But a growing movement is encouraging gardeners to source their plants locally, particularly if you live in a hot place already.

Even a specially developed plant like the Tutti may not thrive in every new location, but plants that have been bred in place are often uniquely adapted to a region in ways we have yet to fully understand. Indigenous communities across the American Southwest, for example, excel at growing heat-tolerant varieties, says Andrea Carter, a member of the Powhatan Renape Nation and director of agriculture and education at Native Seeds SEARCH, a public seed bank in Tucson that preserves arid-adapted seed diversity.

“These seeds have been grown for hundreds, sometimes thousands of years in a particular location — that’s a lot of work that went into adapting those plants,” she says. “In the future, more of the world is going to deal with high temperatures and low water availability, and so the seeds of this region are a real resource that is already becoming more valuable.”

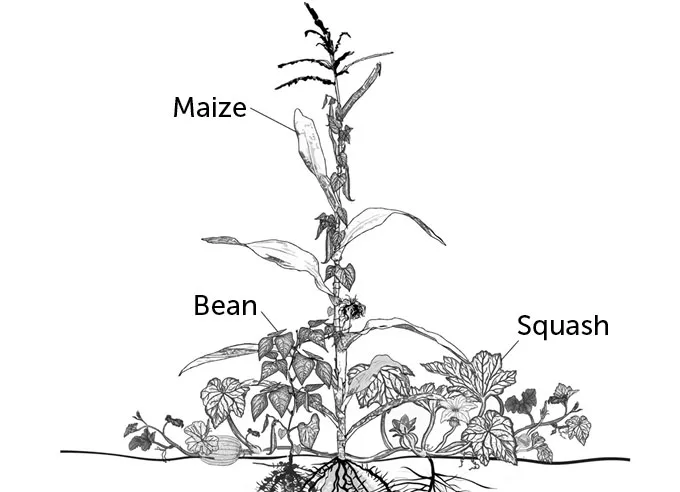

How you grow your plants can also give them an edge (SN: 3/9/23). The “three sisters” method involves growing a trio of corn, beans and squash together, with each providing benefits to the others. Beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn, whose tall stalks provide a trellis for the beans, and the low-growing squash shades the ground. Covering soil with straw or mulch or using shade cloth provides a similar benefit, and Carter says that watering deeply, but infrequently is better than drip irrigation at encouraging roots to grow down, where they are less prone to drying out.

“Desert-adapted plants do that naturally, but others might need a little coaxing,” says Roslynn McCann, a sustainable communities researcher at Utah State University in Moab. “In some ways, I think gardening under climate change has become a little more hands-on in that way. It’s less about throwing seeds out and seeing what grows, and more about doing what you can to give your plants a leg up.”