AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine isn’t tied to blood clots, experts say

Reports of blood clots in people who received the shot had raised concerns

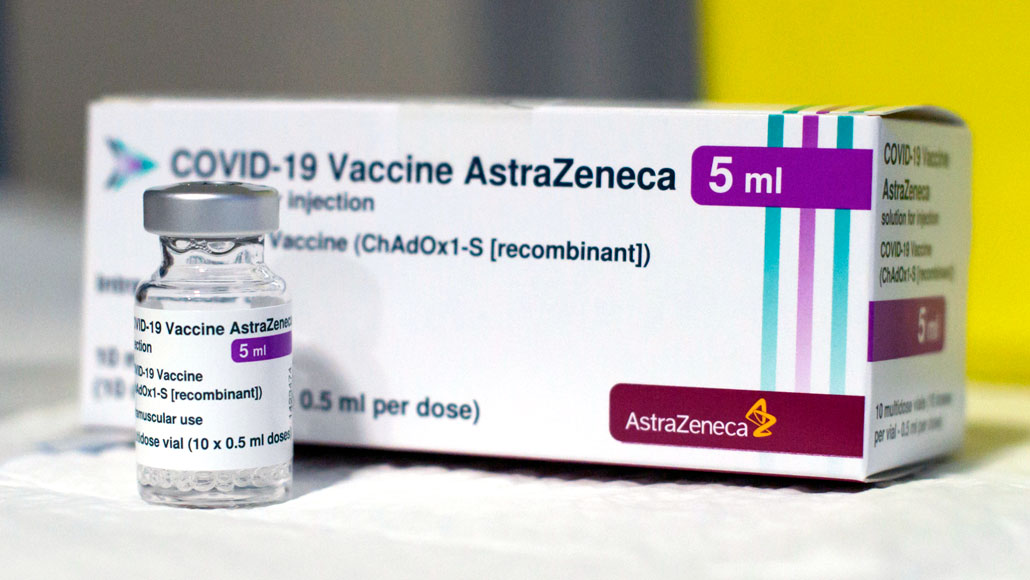

AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine (shown) has been tied to reports of blood clots. A safety committee with the European Medicines Agency found that there is no overall increased risk of blood clots, though officials are still monitoring some rare cases.

hoto by Gustavo Valiente/SOPA Images/Sipa USA via AP

AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine is not associated with an increased risk of blood clots, the European Medicines Agency announced March 18. That’s the conclusion of an investigation conducted by an EMA safety committee into reports of blood clots in some vaccinated people.

“This vaccine is a safe and effective option to protect citizens against COVID-19,” Emer Cooke, executive director of the EMA said March 18 in a news conference.

Starting March 11, many countries, mostly in Europe, began suspending use of a COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford because of concerns it could be linked to blood clots. Of more than 17 million people vaccinated in the European Union and the United Kingdom, there were around 470 reports of blood clots in the days after getting the shot. That rate is lower than how often people normally develop blood clots in daily life, Sabine Straus, chair of the EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee, said during the news conference.

But some uncertainties remain over a few rare case reports, Straus said. Eighteen patients who received the vaccine developed blood clots in the sinuses that drain blood from the brain, a potentially deadly condition called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Another seven people developed disseminated intravascular coagulation, or DIC, in which blood clots can develop throughout the body and block small blood vessels. Nine people died. But there were not enough data to conclude whether these cases might be related to the vaccine, Straus said.

Based on data from before the pandemic, fewer than one DIC case might be expected by March 16 in people younger than 50 years old within two weeks of getting the vaccine, the agency said in a press release. The EMA committee, however, reviewed five such cases. There might also be 1.35 cases of sinus clots on average in that age group, but countries reported 12 by March 16.

Even in light of the reports, “I think the risk is worth taking,” says Elliott Haut, a blood clot expert and trauma surgeon at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “Half a million people died in the United States from [COVID-19] — you don’t want to get this disease.”

The EMA committee will continue to monitor any additional cases of DIC or blood clots in the brain’s sinuses. The agency also recommends that AstraZeneca add a warning to the information provided to physicians and to patients who receive the vaccine to raise awareness.

It’s still unclear why some patients might develop blood clots after vaccination. One possibility is that some vaccinated people might have previously had COVID-19, which can also cause blood clots (SN: 11/2/20).

The EMA committee’s review found that DIC or brain blood clots were more common in women, particularly younger women. It’s too early to know for sure, however, because there is not enough data to rule out other explanations, Straus said. The risk of blood clots may be higher in that group in general — such as women on birth control — or it could be that more women have been vaccinated than men.

But the pattern might also be coincidence, particularly for the reports of less dangerous blood clots. “Blood clots are super common,” Haut says. “It’d be very different for a very uncommon disease to be starting to pop up. Then I think I’d be a little more concerned.”

AstraZeneca previously announced in a news release March 14 that a review of safety data from more than 17 million vaccinated people, the same used in the EMA’s analysis, revealed no connection to blood clots.

The World Health Organization also investigated reports of blood clots after vaccination with AstraZeneca’s jab and similarly concluded that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risk, according to a March 19 statement. “In extensive vaccination campaigns, it is routine for countries to signal potential adverse events following immunization,” the health agency said in a statement March 17. “This does not necessarily mean that the events are linked to vaccination itself, but it is good practice to investigate them.”

The shot is not yet authorized for use in the United States.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.