Stay-at-home orders to slow the coronavirus’ spread caused cuts in greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. But traffic lulls on normally busy highways, like the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (pictured) in New York City, won’t curb climate change.

Alex Potemkin/iStock Unreleased/Getty Images

To curb the spread of COVID-19, much of the globe hunkered down. That inactivity helped slow the spread of the virus and, as a side effect, kept some climate-warming gases out of the air.

New estimates based on people’s movements suggest that global greenhouse gas emissions fell roughly 10 to 30 percent, on average, during April 2020 as people and businesses reduced activity. But those massive drops, even in a scenario in which the pandemic lasts through 2021, won’t have much of a lasting effect on climate change, unless countries incorporate “green” policy measures in their economic recovery packages, researchers report August 7 in Nature Climate Change.

“The fall in emissions we experienced during COVID-19 is temporary, and therefore it will do nothing to slow down climate change,” says Corinne Le Quéré, a climate scientist at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England. But how governments respond could be “a turning point if they focus on a green recovery, helping to avoid severe impacts from climate change.”

Carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for a long time, making month-to-month changes in CO2 levels difficult to measure as they happen. Instead, the researchers looked at what drives some of those emissions — people’s movements. Using anonymized cell phone mobility data released by Google and Apple, Le Quéré and colleagues tracked changes in energy-consuming activities, like driving or shopping, to estimate changes in 10 greenhouse gases and air pollutants.

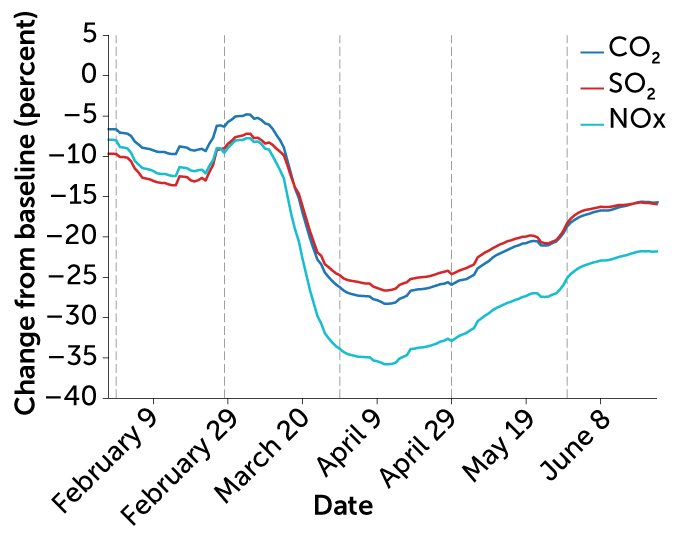

Precipitous drop

Using anonymized cell phone mobility data, scientists estimated how average global emissions changed relative to baseline levels for carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, or SO2, and nitrogen oxides, or NOx, during the coronavirus pandemic. The biggest drops came in April, before emissions began rising again, calculations suggest.

Trends in 3 greenhouse gas emissions during COVID-19, February–June 2020

“Mobility data have big advantages” for estimating short-term changes in emissions, says Jenny Stavrakou, a climate scientist at the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy in Brussels who wasn’t involved in the study. Since those data are continuously updated, they can reveal daily changes in transportation emissions caused by lockdowns, she says. “It’s an innovative approach.”

Google’s mobility data revealed that 4 billion people reduced their travel by more than 50 percent in April alone. By adding more traditional emissions estimates to fill in gaps (SN: 5/19/20), the researchers analyzed emissions trends across 123 countries from February to June. The researchers found that the peak drop occurred in April, when globally averaged CO2 emissions and nitrogen oxides fell by roughly 30 percent from baseline, mostly due to reduced driving.

Fewer greenhouse gases should result in some cooling of the atmosphere, but the researchers found that effect will be largely offset by the roughly 20 percent fall in sulfur dioxide emissions in April. These industrial emissions turn into sulfur aerosol particles in the atmosphere that reflect sunlight and thus have a cooling effect. With fewer shading aerosols, more of the sun’s energy can heat the atmosphere, causing warming. On the whole, the stark drop in emissions in April alone will cool the globe a mere 0.01 degrees Celsius over the next five years, the study finds.

In the long-term, the massive, but temporary, shifts in behavior caused by COVID-19 won’t change our current warming trajectory. But large-scale economic recovery plans offer an opportunity to enact climate-friendly policies, such as invest in low-carbon technologies, that could avert the worst warming (SN: 11/26/19). That could help reach a goal of cutting total global greenhouse gas emissions by 52 percent by 2050, limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels through 2050, the researchers say.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.