Lockdowns may have averted 531 million coronavirus infections

In the United States alone, an estimated 60 million infections were avoided, researchers say

As coronavirus cases began to spike earlier this year, cities around the world were shut down, and officials encouraged such social distancing as seen on this sign posted in Mission Dolores Park in San Francisco. Two new studies find that the lockdowns were effective at greatly reducing coronavirus infections overall.

DutcherAerials/iStock/Getty Images Plus

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

Lockdowns implemented in some countries to reduce transmission of the coronavirus were extremely effective at controlling its rapid spread and saved millions of lives, two new studies suggest.

Shutdowns prevented or delayed an estimated 531 million coronavirus infections across six countries — China, South Korea, Iran, Italy, France and the United States — researchers from the University of California, Berkeley report June 8 in Nature.

And shutdowns saved about 3.1 million lives across 11 European countries, scientists at Imperial College London estimate in a separate study. In Europe, interventions to reduce the coronavirus’ spread brought infection rates down from pre-intervention levels by an average of 81 percent, the team reports also in Nature June 8. In all countries, R naught — an estimate for how many people an infected person might transmit the virus to — was less than one, meaning that each infected person passed the virus on to less than one person on average. With that level of viral transmission, the pandemic would eventually die out in lockdown scenarios.

As the number of COVID-19 cases in some regions first began to spike in January, February and March, governments in places like China, the United States and Italy enforced measures such as social distancing, closing schools and restaurants as well as restricting nonessential travel (SN: 4/1/20). The shutdowns disrupted economies around the globe and resulted in massive job losses, but, until now, it was unclear how effective the measures were at curbing the virus’ spread.

The new findings suggest that “these control measures have worked,” says Alun Lloyd, a mathematical epidemiologist at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, who was not involved in either study. Lockdowns “have saved or delayed many infections and deaths.”

But as countries reopen, residents may face a new surge of infections.

“We’re very far from herd immunity,” Seth Flaxman, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London, said in a news briefing on June 8. Herd immunity refers to the number of people who would need to be immune to the coronavirus — either with a vaccine or by contracting and recovering from the virus — to protect the population as a whole. So far, around 5 percent of the population in hard-hit places like Italy and Spain have been infected, the team estimates. But researchers estimate that around 70 percent of people would need to be immune to achieve herd immunity (SN: 3/24/20).

“The risk of a second wave happening if all interventions and all precautions are abandoned is very real,” Flaxman says.

In the Berkeley study, researchers determined how effective various interventions were in different countries by analyzing data in a manner typically used in economics to assess economic growth. That “econometric” method allowed the team to estimate the effect of more than 1,700 local, regional and national policies to restrict travel, close businesses or keep residents at home on the pandemic’s growth rate. The team analyzed how fast outbreaks in China, South Korea, Iran, Italy, France and the United States were growing on a daily basis before and after governments implemented such policies. The researchers did not estimate the number of lives saved.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

“Without these policies deployed, we would have lived through a very different April and May,” Solomon Hsiang, a data scientist at UC Berkeley, said in the June 8 news briefing.

Overall, the researchers found that lockdowns prevented — or delayed, as the pandemic is not over yet — an estimated 62 million confirmed COVID-19 cases in those six countries. But not everyone who gets infected with the coronavirus gets tested or even shows symptoms, making the true total of averted infections closer to 530 million people, the team estimates.

In the United States, without the lockdown there may have been 4.8 million more confirmed cases and 60 million total infections. One caveat, however, is that the estimates rely on available diagnostic data — and diagnostic testing in the United States has faced shortages and delays (SN: 4/17/20).

Keeping residents home, closing businesses and social distancing were highly effective at curbing the pandemic’s growth overall, the researchers conclude.

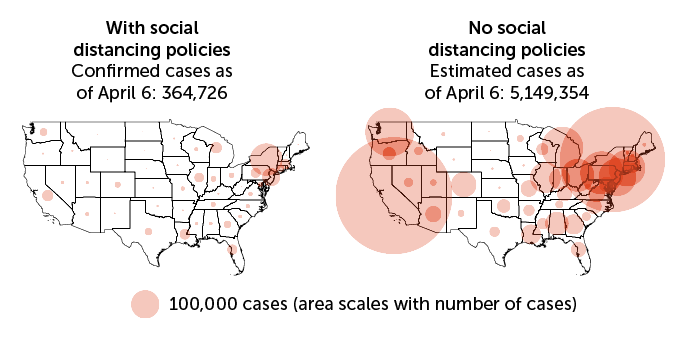

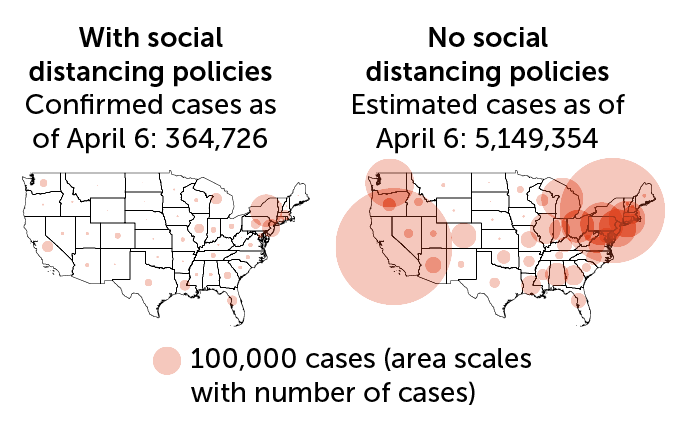

Fewer cases

A study from the University of California, Berkeley estimates that without social distancing policies, including stay-at-home orders and business closures, there may have been 4.8 million more confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States as of April 6. The size of the circles depicts the number of reported coronavirus cases in each state with social distancing policies in place (left) and an estimate of case numbers without control measures (right).

U.S. coronavirus cases as of April 6, actual and estimate without social distancing

Surprisingly, closing schools didn’t appear to curb the outbreak’s growth rate in places like the United States. But it’s still unclear how much of a role kids have in spreading the disease (SN: 6/3/20).

What’s more, “in some contexts, schools were actually closed already during the period when we started analyzing the data,” Hsiang said. That makes it hard to know if the results might have been different if schools were open.

In the Imperial College London study, Flaxman and his colleagues used the number of reported COVID-19 deaths from the beginning of the pandemic up to May 4, when Italy and Spain relaxed their lockdowns, to estimate how many people had been infected. By May 4, as many as 15 million people in 11 European countries — including Denmark, Germany, Italy, France and Spain — may have been infected with the coronavirus without lockdowns, the study suggests. The team then compared the number of deaths that the analysis predicted without lockdowns with those deaths actually reported and calculated that around 3.1 million people would have otherwise died.

Those estimates may be higher than reality, says Julie Swann, a systems engineer also at North Carolina State University. The study used an infection fatality rate — a measure of deaths per number of infections, which includes people who never developed symptoms — that is on the upper end of current estimates for the coronavirus. A higher infection fatality rate could result in an overestimation of the actual numbers.

The results are also based on the assumption that things like school closures or social distancing had the same effect in all countries, which may not reflect reality. And the estimates rely on the premise that people would behave the same way throughout the study period. But “people’s behavior changes in response to what they see is going on around them,” Lloyd says. “If things don’t seem bad, people might be less likely to comply [with control measures]. But when things are much worse, people are more likely to comply.”

And in the Imperial College London study, it’s still unclear how much individual policies helped in reducing cases. Typically, smaller measures, like social distancing, get implemented first, and the big drop happens when a lockdown is introduced, Lloyd says. But “because [the policies] all happened at a similar time, it’s hard to disentangle,” he says.