Creating fat that burns calories

Researchers find a way to make energy-using brown fat from skin cells

Researchers have whipped up a batch of calorie-burning brown fat cells, a feat which may ultimately lead to new ways to treat obesity and metabolic disorders such as diabetes, a paper published online July 29 in Nature reports.

“Brown adipose tissue is coming to the forefront of research in diabetes and obesity because its role is burning energy,” says Francesco Celi, an endocrinologist at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Bethesda, Md.

Unlike energy-storing white fat, brown fat burns energy. Known to keep small animals and dimply babies warm in cold temperatures, brown fat has been shown recently to be present in adults (SN: 5/9/09, p. 10). This finding made researchers think it might be feasible to combat obesity by increasing the amount and activity of brown fat stores in the adult body.

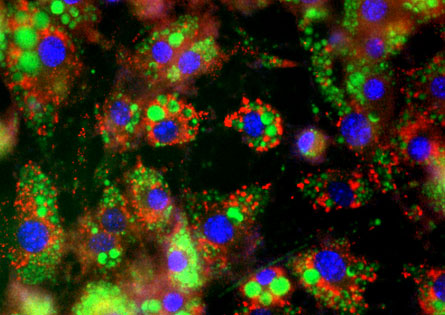

Researchers knew that a protein named PRDM16 was important for producing brown fat cells from pre-muscle cells called myoblasts. In the new study, Bruce Spiegelman of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass., and his colleagues found that PRDM16 requires a partner, called C/EBP-beta. Either protein on its own had no effect on mouse myoblasts in a lab dish. These myoblasts divided as usual. But when researchers increased the amount of both proteins, cells divided to create functional energy-burning brown fat cells, in addition to copies of themselves. Uncovering this method to make brown fat cells, Spiegelman says, “offers us an opportunity to play with the switch.”

Initial experiments were conducted with mouse myoblasts, but the team also found that the method worked on cells taken from mouse skin and from a baby’s foreskin.

These new brown fat cells had many of the same properties as bona fide brown fat cells, Spiegelman says. “They certainly look like they are brown adipose tissue,” he adds.

This ability to make brown fat cells could lead to new treatments, Spiegelman says. One way to bump up a person’s brown fat stores would be to remove a person’s cells, engineer them to produce the two proteins and then put them back in the body to go forth and create brown fat cells. Another approach, Spiegelman says, could be to find synthetic compounds that cause cells already in a person to divide into brown fat cells.

Unlike natural brown fat cells, though, which are able to tune energy consumption (and heat production) to adapt to different conditions, these newly created fat cells appear to always have their thermostats set to high. This may be a problem for therapeutic interventions, comments Leslie Kozak of Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La. Constantly burning the maximum amount of energy would produce a lot of heat. “A constant fever would not be desirable,” he says.

What’s more, the two proteins required for the switch to brown fat might have many other targets, and therefore unintended consequences, in the cell, Kozak says. “However,” says Kozak, “the complications…should not diminish enthusiasm for brown fat.”

To see if the cells could actually function as energy burners in an animal, the researchers transplanted some of the engineered mouse cells into live mice. Engineered brown fat cells formed distinct fat pads at the injection site, near the mice’s hearts. Spiegelman says the cells integrated fully into the animal and appeared to have no harmful effects on the mice. “They did just fine,” he says.

The new cells were not only harmless, but also appeared to be slurping up sugar. PET scans of the mice revealed that the new brown fat pads served as a glucose sink. The pads lit up with fluorescent sugar molecules, indicating that the brown fat cells likely were burning the glucose. Nearby stores of injected white fat showed no energy-burning signal in the PET scan.

The amount of brown fat injected into the mice was too small to change the animals’ overall metabolic rate, Spiegelman says. More studies will be needed to test how much brown fat would be required to make the animals burn more calories.

Understanding how brown fat develops may ultimately lead to better ways to treat diseases like diabetes. This research is still in its early days, Celi says. “At the present time, this is not an immediate intervention [for obesity], but it is definitely something to look forward to in the long run.”