Brains of former football players showed how common traumatic brain injuries might be

Signs of degenerative brain disease are also found in former high school and college athletes

HARD KNOCKS By studying the brains of former football players, researchers are finding clues about how a neurodegenerative disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, progresses, with the hopes of one day preventing it.

Tom Pennington/Getty Images

![]() There have been hints for years that playing football might come at a cost. But a study this year dealt one of the hardest hits yet to the sport, detailing the extensive damage in football players’ brains, and not just those who played professionally.

There have been hints for years that playing football might come at a cost. But a study this year dealt one of the hardest hits yet to the sport, detailing the extensive damage in football players’ brains, and not just those who played professionally.

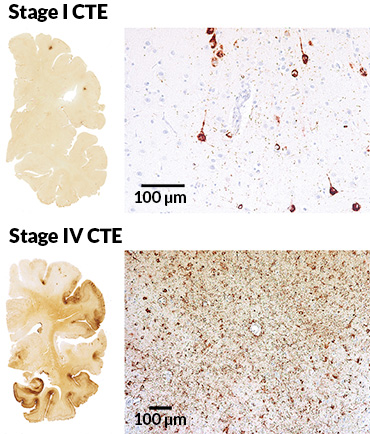

In a large collection of former NFL players’ postmortem brains, nearly every sample showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a disorder diagnosed after death that’s associated with memory loss, emotional outbursts, depression and dementia. Damaging clumps of the protein tau were present in 110 of 111 brains, researchers reported in JAMA (SN: 8/19/17, p. 15).

Those startling numbers captured the attention of both the football-loving public and some previously skeptical researchers, says study coauthor Jesse Mez, a behavioral neurologist at Boston University. “This paper did a lot to bring them around.” And that increased awareness and acceptance has already pushed the research further. “The number of brain donors who have donated since the JAMA paper came out has been astronomical,” Mez says.

As the largest and most comprehensive CTE dataset yet, the results described in JAMA are a necessary step on the path to finding ways to treat or prevent CTE, and not just for professional athletes.

Former college and high school football players’ brains were also examined, though in small numbers. Three of 14 high school players and 48 of 53 college players had signs of CTE. Many of the brains were donated by relatives who suspected something was amiss. That skewed sample makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions. Still, the study raised troublesome questions about the safety of youth sports.

Those questions haven’t been answered, though other research this year provided clues. A study of concussed hockey players ages 11 to 14 suggested that young brains may need more time than is usually allotted to heal after a hard knock. Players had troublesome changes in white matter tracts — nerve cell bundles that carry messages across the brain — three months after injury, despite normal thinking and memory abilities, researchers reported in November in Neurology.

To fully understand CTE, scientists need a way to identify and follow the disease as it progresses. A comprehensive study is now under way to look for CTE markers in live people, and has already hit on one clue.

Compared with postmortem brain tissue taken from healthy people and those with Alzheimer’s, tissue from people who had CTE had higher levels of an inflammation protein called CCL11, Mez and other researchers reported in September in PLOS ONE. In people with CTE, the more years that a person played football, the more CCL11. CCL11 levels, or other factors circulating in cerebrospinal fluid or blood, might one day let scientists monitor the brain health of athletes and others exposed to head trauma.