‘Dinosaur 13’ details custody battle for largest T. rex

Documentary tells story of dinosaur skeleton nicknamed Sue and who owns her

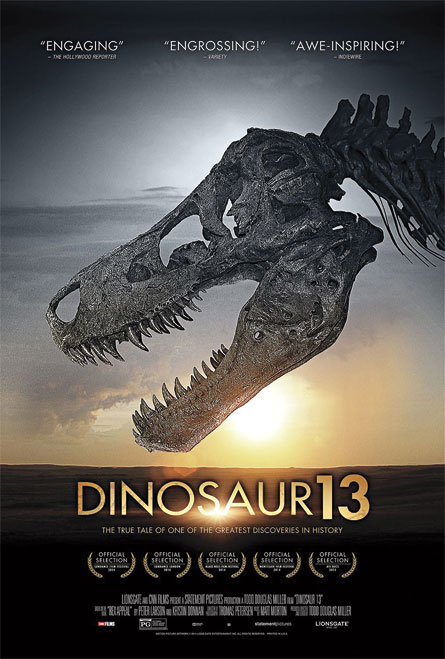

Dinosaur 13

Dinosaur 13

Todd Douglas Miller

Lionsgate 2014

The morning of August 12, 1990, didn’t seem like a good one for fossil hunting. Thick fog clung to the South Dakota prairie where Peter Larson and other collectors had been digging for dinosaur bones, and their ’75 Suburban had a flat tire.

But while Larson fixed the truck, Susan Hendrickson hiked through the murk and struck dino gold. There, embedded in the side of a cliff, she found a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton — the biggest, most complete specimen ever discovered.

It may also be one of the most fought-over. Dinosaur 13 chronicles the T. rex’s tumultuous journey from its burial spot to its eventual display in Chicago’s Field Museum and dives into the dino’s tangled custody battle.

After Hendrickson’s discovery, the team dubbed the dinosaur Sue, eased her bones from the cliffside and hauled them back to Larson’s Black Hills Institute of Geological Research, which sells and displays fossils. For two years, the team cleaned the fossils and organized the delicate, jumbled bones.

“We were riding on top of the world,” says Larson’s brother Neal. Then, he says, “All hell broke loose.”

On May 14–16, 1992, the FBI and the National Guard swooped in and carted the dinosaur away.

Larson’s team spent over a decade fighting to get her back. On the other side of the battle stood the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe, a landowner portrayed as looking to get rich quick and the federal government, who held the land of Sue’s discovery site in a trust. Both sides vied to convince a judge of Sue’s rightful owner, and whether or not Larson’s team conspired to steal the federal government’s property.

The documentary highlights the rift between collectors like Larson, who sell fossils, and academic paleontologists, whose interests may not be as commercial. Though the film is more Law & Order than Jurassic Park, and dinosaur lovers may wish for more information, we do get a few bits about Sue’s life. Violent injuries, including a broken skull and a lower jaw ripped from the socket, suggest that she may have died in an attack by another T. rex, Larson says.

But Dinosaur 13’s focus isn’t so much Sue as it is her discoverers. We’re primed to see the story from their perspective and feel the agony of lost research and a dinosaur wrenched from her home.