Drowned land holds clue to first Americans

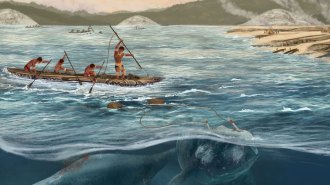

Combining the skills of the late Jacques Cousteau and Louis Leakey, two Canadian researchers have gone off the deep end to address one of the biggest questions in anthropology: How did people first make their way to the Americas? Using sophisticated underwater techniques, the scientists have mapped out a now-flooded route that could have provided an entry point into the New World during the last ice age.

“What they’re doing is very pioneering. It’s a beautiful bit of science,” comments archaeologist E. James Dixon of the Denver Museum of Natural History. The Canadian research adds weight to the idea that maritime Asians migrated down the coast of North America instead of hoofing it overland, as anthropologists have traditionally believed.

Daryl W. Fedje of Parks Canada in Victoria, British Columbia, and Heiner Josenhans of the Geological Survey of Canada in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, carried out the new study off the coast of the Queen Charlotte Islands, just south of Alaska. The researchers used high-resolution sonar to complete a detailed bathymetric map of the underwater landscape.

The chart, published in the February Geology, shows a drowned world of former river valleys, flood plains, and ancient lakes that would have been above sea level at the end of the last glacial epoch, more than 10,000 years ago. During the ice age, so much of the world’s water was locked up in continental glaciers that the height of the oceans dropped by 120 meters.

The narrow seas separating Siberia and Alaska dried up, forming a temporary land bridge between the two continents. Using the new map, Fedje and Josenhans went out to collect samples from the coastal seafloor. They found a pine tree stump and other woody debris that date to 12,200 years ago, according to the carbon-14 method. This is the earliest direct evidence that forests had returned to the formerly ice-covered area. Other sites yielded shells from edible shellfish dating almost to the same time.

Such clues show how the coastline, which was frozen until about 14,000 years ago, was growing more hospitable. “At this time, 12,000 years ago, it would have been a suitable place for people to live and be moving across,” says Fedje.

The researchers also found a stone tool at a location now 53 m below sea level. They have dated this site to 10,000 years ago, making the tool one of the earliest human artifacts along the northwest coast of North America.

The new evidence goes against the long-held assumptions of anthropologists who theorized that the first human immigrants must have been hunters following mammoths and other large game via an inland route to the North American Great Plains. Once people passed over the land bridge to Alaska about 12,000 years ago, according to the older theory, they trekked through a narrow corridor between two remaining giant ice sheets, one covering northeast North America and the other blanketing the Rocky Mountains and their northern extension.

Recently, however, archaeologists have discovered evidence of people reaching South America by 12,500 years ago, well before the ice-free inland corridor would have been passable. “People are looking increasingly toward the coast as an alternative option for getting to the lower 48 states and other portions of the New World,” says archaeologist David Meltzer of Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “That’s why this kind of [mapping] work is interesting and important, because it’s helping to show us when such routes would have been open, viable, and possibly traversable.”

Meltzer notes, however, that coastal migrants must have arrived well before the time of the forests documented by Fedje and Josenhans, in order to spread all the way to the southern end of South America by 12,500 years ago. Regarding the evidence of human migration, he says, “the further we push it back, the happier I’ll be.”