Facebook data show how many people left Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria

An ad platform on the site could be used to quickly track migrations after natural disasters

TRACKING MIGRANTS After Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, many residents fled to the mainland United States. Researchers estimated that exodus using Facebook data — evidence that social media can provide rough, real-time estimates of migrations of people following natural disasters, the team says.

Alessandro Pietri/Shutterstock

Hurricane Maria sent Puerto Ricans fleeing from the island to the U.S. mainland, but population surveys to assess the size of that migration would have taken at least a year to complete. A new study suggests, however, that a Facebook tool for advertisers could provide crude, real-time estimates for how many people are moving because of a natural disaster. That could help governments design policies to assist those displaced people.

The Facebook data revealed that, from October 2017 to January 2018, the Puerto Rican population on the mainland increased by some 17 percent, or about 185,200 residents. That would imply a 5.6 percent decrease in the population living the U.S. Caribbean territory.

Almost a third of those migrants, or about 65,400 people, went to Florida, the data suggest. Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts each also received about 8,000 to around 15,000 new migrants from Puerto Rico. About 19,500 Puerto Ricans appear to have returned home from January to March 2018, researchers report April 11 in Austin, Texas, at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America.

Overall, the migration estimate is in line with the official estimate of 159,415 Puerto Ricans having relocated to the mainland one year after the hurricane.

Scientists acknowledge that relying on social media data has drawbacks, including an inability to control data samples. Facebook use is limited in many countries, and users may not represent the general population.

There is also no way to check the company’s demographic data for accuracy, says Fabrício Benevenuto, a computer scientist at Federal University at Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, who was not involved in this research. “The algorithm provided by Facebook is not public, so it’s a black box.”

The study, also published online on the preprint server SocArXiv, is a proof of concept, says coauthor Monica Alexander, a sociologist and statistician at the University of Toronto. “Despite all these problems, we are still getting a signal that’s measurable and useful to track [demographic] changes,” she says.

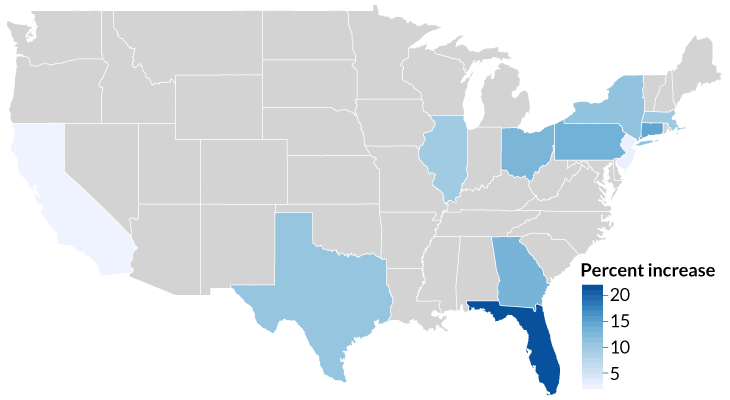

Fleeing to the mainland

Data from a Facebook application for advertisers suggests that in the three months after Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico in September 2017, Florida’s population of Puerto Ricans swelled the most in the country. It rose by almost 22 percent, or around 65,400 people, researchers say. Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts also saw substantial gains of 8,000 to 15,000 migrants, the team estimates. (Only states with a Puerto Rican migrant population of at least 18,000 are depicted.)

Estimated increase in Puerto Rico migrants to the mainland United States,

October 2017-January 2018

Estimated increase in Puerto Rico migrants to the mainland United States, October 2017-January 2018

Alexander and her colleagues used the Facebook tool Ads Manager, which lets advertisers gauge the size and composition of a target audience. By creating target groups according to age, sex and place of origin — such as ages 25 to 35, female and Puerto Rican — the team could estimate how the Puerto Rican population in the U.S. mainland changed in size and profile over the period studied. (The program is free for users like Alexander who are not using the information to create targeted ads.)

The researchers had already spent months testing whether Ads Manager could help track all migrants to the contiguous United States when Hurricane Maria hit the Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands in September 2017. The team then zoomed in on mainland U.S. populations of Puerto Ricans in January 2018.

The raw Facebook data can be misleading, Alexander says. Some of the fluctuations in migrant populations revealed by Ads Manager could be tied to changes in the program itself. To correct for those fluctuations, the researchers created a control group of long-term visitors to the United States that would not have been affected by the hurricane. Comparing trends in the Puerto Rican groups with trends in the control group allowed the team identify which fluctuations came from programmatic glitches.

Comparing the data against a control group led the researchers to a new finding: post-hurricane migration from Puerto Rico appeared to skew young and male. Migrants ages 15 to 30 from the island made up 23 percent more of the overall Puerto Rican migrant population than in the control group. The Puerto Rican migrant group was also about 2 percent more comprised of men.

By March 2018, the mainland Puerto Rican population had shrunk back down by almost 2 percent, which the team assumed meant some individuals had returned home.

“Accurate data on migration flows is not readily available in any given year, so we have to get proxies,” says economist Edwin Meléndez of Hunter College in New York City, who was not involved in the research. Those proxies can help elucidate migration trends, he says, until official estimates come later.