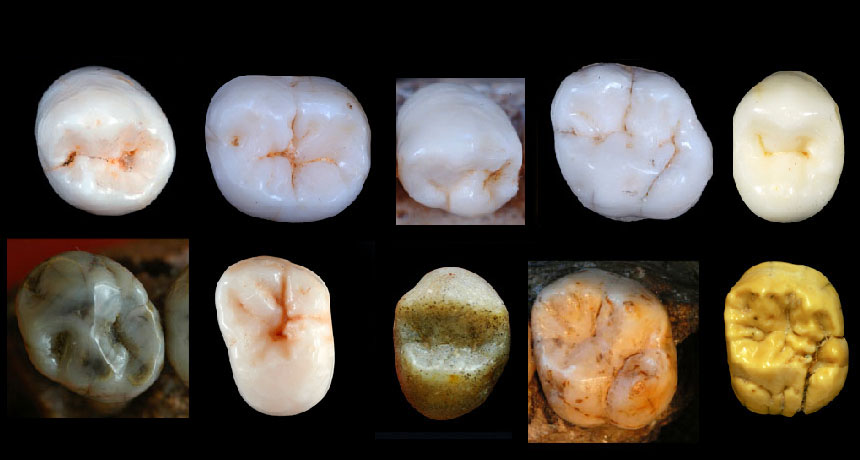

Fossil teeth push the human-Neandertal split back to about 1 million years ago

A new study estimates the age of these hominids’ last common ancestor

CROWNING ROOTS An analysis of hominid tooth evolution, including specimens from Spanish Neandertals (top row), pushes back the age of a common Neandertal-human ancestor to more than 800,000 years ago. The bottom row shows Homo sapiens teeth.

A. Gómez-Robles, Ana Muela and Jose Maria Bermudez de Castro