News of the first gene-edited babies ignited a firestorm

Chinese researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 to alter a gene to block HIV infection

DATA DELIVERY On November 28, researcher Jiankui He gave scientists a first glimpse of data from the creation of two gene-edited babies. Many in the scientific community have decried the work.

S.C. Leung/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images

A Chinese scientist surprised the world in late November by claiming he had created the first gene-edited babies, who at the time of the announcement were a few weeks old. Scientists and ethicists quickly responded with outrage.

In an interview with the Associated Press and in a video posted November 25, Jiankui He announced that twin girls with a gene altered to reduce the risk of contracting HIV “came crying into this world as healthy as any other babies.”

Many researchers and ethicists say implanting gene-edited embryos to create babies is premature and exposes the children to unnecessary health risks. Critics also fear the creation of “designer babies,” children edited to enhance their intelligence, athleticism or other traits.

Facing his peers on November 28 in Hong Kong at the second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, He explained his research. He also revealed that another woman participating in a gene-editing trial is in the early stages of pregnancy (SN Online: 11/28/18).

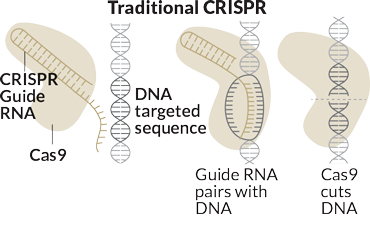

He said his group used the gene-editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 to disable the CCR5 gene in the fertilized eggs that produced the babies, “Lulu” and “Nana” (not their real names). CCR5 encodes a protein that allows the most common version of the HIV virus to enter cells. Some people naturally have versions of the gene that help protect against HIV infection.

The girls’ parents were one of seven couples recruited from an HIV patient group to take part in what was called an HIV vaccine development project. The twins’ father has HIV; their mother does not.

He claimed that his experiments to disable CCR5 might help susceptible children, especially in the developing world, avoid HIV infection. “I truly believe this is not only just for this case, but for millions of children that need this protection since an HIV vaccine is not available.… I feel proud.”

But scientists say there was almost no chance the girls would have been infected with HIV at birth since their mother doesn’t carry the virus. And there are easier and safer ways to avoid infection after birth.

Researchers who saw He’s presentation were not convinced that he presented enough evidence to verify that the editing was successful and didn’t damage other genes. Previous CRISPR/Cas9 research has indicated that some cells in embryos may be incompletely edited or escape editing entirely, creating a “mosaic” embryo (SN: 9/2/17, p. 6).

In this case, incomplete editing might leave the children as vulnerable to HIV infection as if their DNA had never been altered. Lulu’s edited copies of CCR5 supposedly mimic the natural variants that give people HIV resistance. Whether the version of the gene He claims Nana carries confers resistance to HIV is not known. Previous claims of successful gene editing in human embryos in lab dishes also have been met with skepticism (SN Online: 8/8/18).

Until now, scientists around the world have abided by a consensus that creating babies with edited embryos goes too far, because safety and ethical issues haven’t been resolved. “I assume you’re very well aware of this redline,” Wensheng Wei of Peking University in Beijing said after He’s presentation. “Why did you choose to cross this line? And … why did you choose to do all these clinical studies in secret?” He did not answer the questions.

Gene editing may sometimes damage other important genes, which could lead to health problems such as cancer later in life. And taking a gene out of commission has risks: People with missing or defective CCR5 genes are more susceptible to serious complications from West Nile virus infections.

Even if the girls don’t end up with any health problems as a result of He’s genetic tinkering, the experiment is still bad science, says Julian Savulescu, a bioethicist at the University of Oxford. “I liken it to Russian roulette. You can pull the trigger and not kill, but that doesn’t mean what you did was right.”

Within days of He’s announcement, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology suspended work by He and his team at Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China, stating that He’s actions “violated China’s relevant laws and regulations.” Authorities are investigating further.

Organizers of the summit called the work “irresponsible” and expressed doubt over whether the edits happened at all. But they released a statement agreeing that it’s time to set standards for future clinical trials that would produce gene-edited babies to correct diseases.