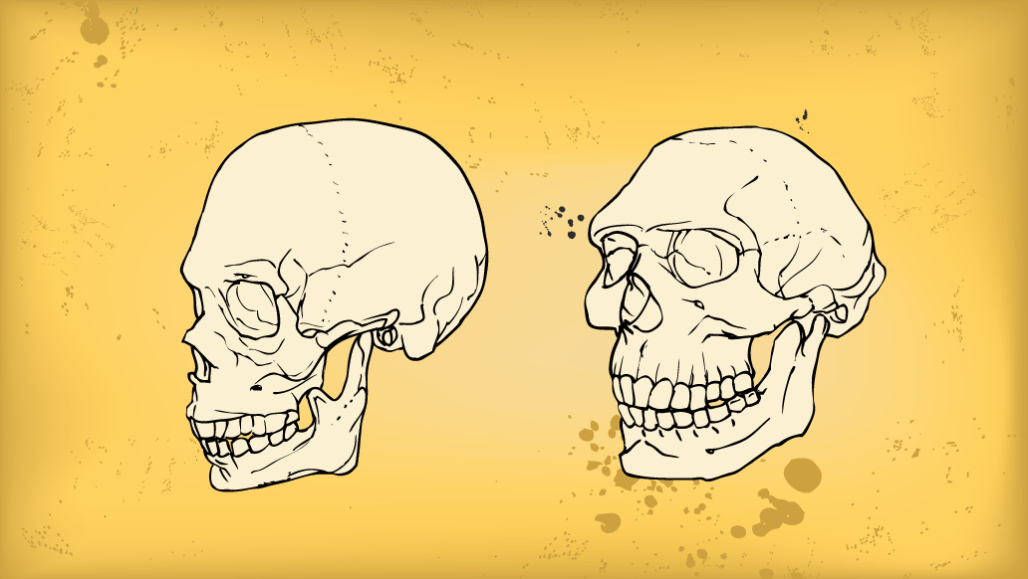

Modern humans (left in this illustration) have flatter, smaller faces than Neandertals (right) did. Now researchers are implicating a gene that affects movement of some developmentally important cells in that change.

heavypred/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images