A gigantic galactic graveyard lurks in the distant universe, and the death toll is growing.

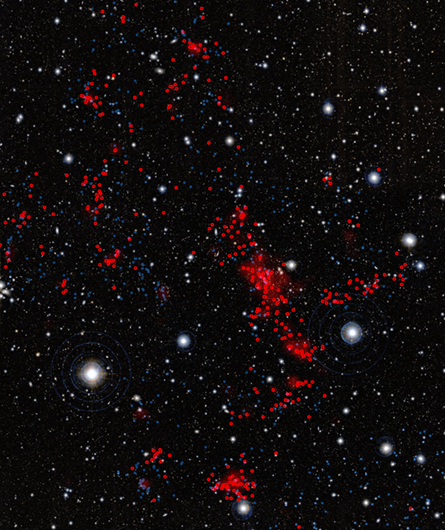

New observations establish a supercluster centered on the cluster CL0016+16 as the largest galactic congregation ever found, astronomers report in Astronomy & Astrophysics. The supercluster extends even farther than previously thought, and it’s drawing in more and more galaxies.

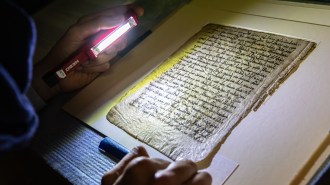

CL0016+16 lies about 6.7 billion light-years away from Earth. That cluster was first observed in 1981, and later observations hinted that it might be just one of a cluster of clusters. Observations by David Koo of the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1996 pointed to a large structure extending from the main cluster.

“There are many predictions for large-scale structure in the universe, but nobody has really confirmed that this large-scale cluster exists in the distant universe,” says Masayuki Tanaka from the European Southern Observatory, a coauthor of the new report. “We actually see this massive structure in the distant universe. Not theory, not prediction — this is the real universe.”

Tanaka and his colleagues made several observations of the region between August 2007 and December 2008 using the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii and the Very Large Telescope in Chile. They found that the supercluster extends at least 60 million light-years in one direction beyond the 100 million light-years already known, and it could reach even farther.

“It must be gigantic,” Koo says. “This thing is not only big, it’s big in the opposite direction from what we saw. It’s probably twice as big as we thought.”

Galaxies that group together tend to switch off each others’ star formation, “bringing a flourishing galaxy into a dead one,” says study coauthor Alexis Finoguenov of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany.

Astronomers think that grouped galaxies speed up, stripping away their neighbors’ hot gas, the raw material for forming stars. When galaxies cluster, “there is always a threshold when groups go from an encouraging environment to a suffocating environment,” Finoguenov says.

Galaxies are known to clump together along dark matter filaments, which grew from slight variations in the concentration of matter after the Big Bang. The filaments extend for millions of light-years in an enormous cosmic web, providing a framework for the universe’s large-scale structure.

Tanaka’s team identified tens of clumps of galaxies surrounding CL0016+16, some of which are up to a thousand times more massive than the Milky Way.

And most of those galaxies are either dead or dying, meaning they’re not making new stars. The tremendous gravitational pull of the central cluster is drawing in other galaxies, which will eventually cease star formation in the growing galactic graveyard.

On the bright side, “this will be an ideal data set to study when, where and how galaxies die,” Tanaka says.

Galaxies near the Milky Way, at least, are at a safe distance from the graveyard. “We will probably never turn into such an environment anyway,” Finoguenov says. “We will keep living.”