Heart attack patients get high radiation dose

Medical imaging can add up to exposure similar to what nuclear power plant workers experience

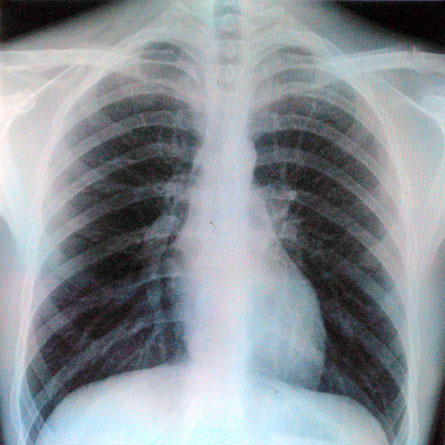

ORLANDO, Fla. — The first large study to examine cumulative radiation exposure from medical imaging after a heart attack has found that the average patient receives the equivalent of about 725 chest X-rays before leaving the hospital. That’s about one-third the maximum radiation dose allowed for a nuclear power plant worker in a given year.

Whether this is enough radiation to be a cancer risk is unclear, the researchers say, but the information should be sobering for physicians and patients.

Among the billions of imaging tests performed each year, about one-third occur during the treatment and diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, said Prashant Kaul, a fellow in cardiovascular medicine at the Duke University Medical Center in Durham, on November 16 at a meeting of the American Heart Association. Radioactive substances are used to produce images that allow doctors to peer inside the heart, commonly to pinpoint the site of artery blockage or determine blood flow. Until now, physicians did not have a sense of how this radiation exposure accumulates, Kaul said.

“We certainly don’t want to be alarmist,” Kaul said. Imaging tests are necessary tools for cardiologists. However, he said, “We’re trying to change the way people think about radiation.”

To gauge how the radiation adds up, Kaul and his colleagues analyzed data from more than 64,000 patients treated in 49 hospitals throughout the United States over more than three years. The researchers reported that the average patient undergoes about four tests during each stay — most often chest X-rays, cardiac catheterizations and CT scans. Taken together, these tests expose each patient to about 14.5 millisieverts of radiation before checking out of the hospital. That is about five times the dose that an average person experiences each year. For safety, nuclear power plant workers are limited to 50 millisieverts annually.

Biological effects of radiation at this level are not known, said Thomas Gerber of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. “Nobody has been able to show that patients at the level of exposure we’re taking about have an increased risk of cancer,” he said.

After a heart attack, “we do what we think is necessary for the patient,” Gerber said. However, the Duke study should give doctors pause before ordering tests for people who are otherwise healthy. And before agreeing to a test involving radiation, patients can ask their doctors whether the results would change their care.

When ordering tests, most physicians think about the risks of radiation from one procedure, not the fact that repeated exposures accumulate, Kaul said. Though imaging tests following a heart attack are not considered to be optional, there may be instances when repeated tests are unnecessary or when similar information can be obtained another way to limit exposure to radiation. “We’re not suggesting important tests be withheld,” he said. “But we want to be sure we’re ordering the right tests for the right patients.”

Medical care involves an increasing number of cardiac procedures, which now account for about one-third of all imaging tests conducted, Kaul says. Statistics from the American Heart Association show that radiation exposure from medical tests has increased sevenfold since 1980.

Kaul also expressed hope that radiation exposure will be a consideration when patients are transferred from one hospital to another after a heart attack. Sometimes tests performed at one hospital will be ordered again at the second, Kaul said. “We think it’s more appropriate to think about radiation for an entire episode of care.”