Unexplained hepatitis cases in kids offer more questions than answers

The instances are still rare and parents shouldn’t panic

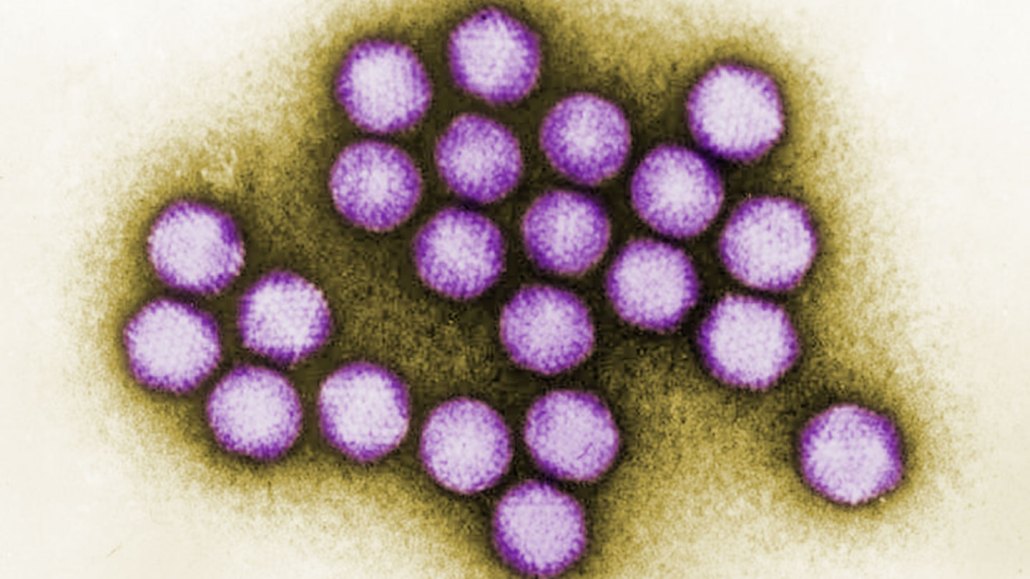

Some of the children who have recently developed unexplained hepatitis also tested positive for adenovirus, shown in this colorized transmission electron microscope image.

G. William Gary, Jr./CDC

As health officials continue their investigation of unexplained cases of liver inflammation in children, what is known is still outpaced by what isn’t.

At least 500 cases of hepatitis from an unknown cause have been reported in children in roughly 30 countries, according to health agencies in Europe and the United States. As of May 18, 180 cases are under review in 36 U.S. states and territories.

Many of the children have recovered. But some cases have been severe, with more than two dozen of the kids needing liver transplants. At least a dozen children have died, including five in the United States.

The illnesses have mainly been seen in children under age 5. So far, health agencies have ruled out common causes of hepatitis, while reporting that some of the children have tested positive for adenovirus. That pathogen — which infects basically everyone, usually without serious issues — is not known as a primary cause of liver damage. For some children who are positive, officials have identified the particular adenovirus: type 41.

But there are several reasons why pinning an adenovirus as the sole hepatitis culprit doesn’t fully add up, researchers say. Nor is it clear whether the recent cases indicate an uptick in hepatitis illnesses, or just more attention. Though the cases seem to have popped up out of nowhere, “we’ve seen similar rare severe liver disease like this in children,” says Anna Peters, a pediatric transplant hepatologist at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Most of all, it’s important for parents to remember that the cases described so far “are a rare phenomenon,” Peters says. “Parents shouldn’t panic.”

Hepatitis in children

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver that can interfere with the organ’s many functions, including filtering blood and regulating clotting. Three hepatitis viruses, called hepatitis A, B and C, are common causes of the illness in the United States. Hepatitis A is spread when infected fecal material reaches the mouth. Children can get B and C when it’s transmitted from a pregnant person to an infant. There are vaccines available for A and B but not C. An excessive dose of acetaminophen can also cause hepatitis in children.

The signs of hepatitis can include nausea, fatigue, a yellow tinge to skin and eyes, urine that’s darker than usual and stools that are light-colored, among other symptoms. Hepatitis that arises quickly usually resolves, whereas some cases progress more slowly and lead to liver damage over time.

It’s rare for a child to develop sudden liver failure. An estimated 500 to 600 cases occur each year in the United States, and around 30 percent of those are “indeterminate,” meaning a cause isn’t found, according to the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition.

The indeterminate category of sudden liver failure has been known for some time, Peters says, and that subset of cases has similarities to the hepatitis under investigation. There hasn’t been data reported yet on whether the recent cases represent an increase over what’s been seen in prior years, Peters says. “Maybe this is just increased recognition of something that’s been going on.”

Adenovirus as a suspect

Not all of the children with hepatitis have been positive for adenovirus, nor have they all been tested. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, or ECDC, has reported that of 151 cases tested, 90 were positive, or 60 percent. The last dispatch from the U.K. Health Security Agency, from early May, noted that 126 samples out of 163 had been tested, with 91, or 72 percent, positive. Further analysis of 18 cases identified adenovirus type 41.

Adenoviruses commonly infect people, typically causing colds, bronchitis or other respiratory illnesses. Two types, adenovirus 40 and 41, target the intestines, leading to gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea.

“All of these types, including this prime suspect type 41, have been detected everywhere continuously,” says virologist Adriana Kajon of the Lovelace Biomedical Research Institute in Albuquerque. “All of them have existed and have been reported continuously for decades.”

People usually recover from an adenovirus infection. The exception is those whose immune systems aren’t functioning properly — then, an infection can be serious. There have been cases of hepatitis from adenovirus in immunocompromised children, but the kids under investigation are not immunocompromised.

There are several curious details about the adenovirus findings. For example, the children who have tested positive for the virus had low levels in their blood. In cases of hepatitis from adenovirus, “the virus levels are very, very high,” Peters says.

Nor has adenovirus been found in the liver. In a study of nine children with the hepatitis in Alabama who were positive for adenovirus in blood samples, researchers studied liver tissue from six of the kids. There was no sign of the virus in the liver, the researchers report May 6 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“It’s very hard to implicate a virus that you cannot find in the crime scene,” Kajon said May 3 at a symposium for clinical virology in West Palm Beach, Fla.

Another oddity: There doesn’t seem to be a path of viral spread from one location to another. That’s unlike SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, “where there was quite clearly a spread from some epicenter originally,” says virologist and clinician Andrew Tai of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, who treats patients with liver disease.

An adenovirus culprit is not out of the realm of possibility, but “virus associations with diseases are always hard to really nail down and prove,” says virologist Katherine Spindler, also of the University of Michigan Medical School. “We’re going to be hard pressed to say this is due to adenovirus 41, let alone adenovirus.”

Considering COVID-19

Looming over all of this is the possibility that a many-magnitudes-larger infectious disease outbreak, COVID-19, could have a part.

Researchers have found that SARS-CoV-2 impacts the liver in milder and more severe cases of COVID-19. There is evidence that the liver becomes inflamed in children and adults during an infection. Liver failure can occur with a severe bout of COVID-19. And children who develop multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, after COVID-19 can have hepatitis as part of that syndrome.

Peters and her colleagues have described yet another way SARS-CoV-2 could put the liver at risk. The team reported the case of a young female patient from the fall of 2020, who had sudden liver failure about three weeks after a SARS-CoV-2 infection. She did not have MIS-C. A liver biopsy showed signs of autoimmune hepatitis, a type in which the body attacks its own liver, Peters and colleagues report in the May Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition Reports. The patient recovered after treatment with anti-inflammatory medication.

Some of the children with hepatitis have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, but more haven’t. The ECDC has reported that 20 of 173 cases tested were positive for SARS-CoV-2, while the U.K. Health Security Agency detected the virus in 24 of 132 samples tested.

However, there have been very little data reported on whether the children have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, which would be evidence of a past infection. (Vaccination hasn’t been available to most of these young children.) The ECDC found that of 19 cases tested, 14 were positive for antibodies to the virus.

One theory is that an earlier SARS-CoV-2 infection has set the stage for an unexpected response to an adenovirus or other infection. With people no longer minimizing contact, the spread of adenoviruses and other respiratory viruses is returning to prepandemic levels.

“We are possibly seeing the return of these forgotten pathogens, so to speak, aggravating disease or eliciting severe inflammation resulting from some kind of preexisting condition,” which could be COVID-19, Kajon said on May 3.

“I cannot think of anything else that has had a worldwide impact that can explain cases of hepatitis in places as distant as the U.K. and Argentina,” Kajon says.

With SARS-CoV-2, researchers have a good sense of how it causes disease during an active infection, Peters says. But for the longer-term effects, “everybody is still sorting things out.”