How a backyard pendulum saw sliced into a Bronze Age mystery

Researcher’s swinging blade offers glimpse into how ancient Mycenaeans built palaces

ENIGMATIC ENGINEERING An ancient sculpture known as the Lion Gate relief contains marks in a column (center of image) that may have been made by a pendulum saw. The lions, now headless, stood above the main entrance to the citadel of Mycenae, in what is now Greece.

Lulu and Isabelle/Shutterstock

Nicholas Blackwell and his father went to a hardware store about three years ago seeking parts for a mystery device from the past. They carefully selected wood and other materials to assemble a stonecutting pendulum that, if Blackwell is right, resembles contraptions once used to build majestic Bronze Age palaces.

With no ancient drawings or blueprints of the tool for guidance, the two men relied on their combined knowledge of archaeology and construction.

Blackwell, an archaeologist at Indiana University Bloomington, had the necessary Bronze Age background. His father, George, brought construction cred to the project. Blackwell grew up watching George, a plumber who owned his own business, fix and build stuff around the house. By high school, the younger Blackwell worked summers helping his dad install heating systems and plumbing at construction sites. The menial tasks Nicholas took on, such as measuring and cutting pipes, were not his idea of fun.

But that earlier work paid off as the two put together their version of a Bronze Age pendulum saw — a stonecutting tool from around 3,300 years ago that has long intrigued researchers. Power drills, ratchets and other tools that George regularly used around the house made the project, built in George’s Virginia backyard, possible.

“My father enjoyed working on the pendulum saw, although he and my mother were a bit concerned about what the neighbors would think when they saw this big wooden thing in their backyard,” Blackwell says. Anyone walking by the fenceless yard had a prime view of a 2.5-meter-tall, blade-swinging apparatus reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe’s literary torture device.

HEAVE HO Archaeologist Nicholas Blackwell, left, and his brother-in-law Brandon Synan demonstrate how to use a rope to operate a pendulum saw. They tested the rock-cutting device on a piece of limestone in the Virginia backyard of Blackwell’s father, who was instrumental in designing and building the contraption. |

No one alive today has seen an actual Bronze Age pendulum saw. No frameworks or blades have been excavated. Yet archaeologists have suspected for nearly 30 years that a contraption capable of swinging a sharp piece of metal back and forth with human guidance must have created curved incisions on large pieces of stonework from Greece’s Mycenaean civilization. These distinctive cuts appeared during a century of palace construction, from nearly 3,300 years ago until the ancient Greek society collapsed along with a handful of other Bronze Age civilizations. Mycenaeans built palaces for kings and administrative centers for a centralized government. These ancient people spoke a precursor language to that of Classical Greek civilization, which emerged around 2,600 years ago.

In Blackwell’s view, only one tool — a pendulum saw — could have harnessed enough speed and power to slice through the especially tough type of rock that Mycenaeans used for pillars, gateways and thresholds in palaces and some large tombs.

Kings at the time valued this especially hard rock, known as conglomerate, for the look of its mineral and rock fragments, which form colorful circular and angled shapes.

In the early 20th century, archaeologists excavating a Mycenaean hill fort called Tiryns first noticed curved cut marks on the sides of pillar bases and other parts of a royal palace. The researchers assumed that ancient workers sliced through conglomerate blocks with curved, handheld saws and a lot of elbow grease.

Blackwell doubted that Mycenaeans used pendulum saws as tall as 8 meters, the equivalent of about 2½ stories. But there was only one way to find out. His experiments, described in the February Antiquity, indicate that a wooden contraption supporting a blade-tipped swinging arm had to reach only about 2½ meters high to create stone marks like those at Tiryns and Mycenae.

The Indiana researcher’s homemade pendulum saw “is the most persuasive reconstruction of a Mycenaean sawing machine that was used to cut hard stones, especially conglomerate,” says archaeologist Joseph Maran of the University of Heidelberg in Germany. Only one other life-size model of a pendulum saw exists.

Swing time

Blackwell’s experimental cutting device swung into action in December 2015 right where it was built, in his parents’ Virginia backyard.

Positioned on opposite sides of the apparatus, Blackwell and his brother-in-law, Brandon Synan, pulled the sawing arm back and forth with a rope. A metal blade bolted to the bottom of the arm sliced into a limestone block. Unlike the type of conglomerate used in the Mediterranean region, limestone was readily available. The two tested four types of saw blades in the initial trials and again in February 2017.

Blackwell reviewed seven previously published designs and the one actual model of a pendulum saw that may have been used by a nearby Bronze Age society; they offered little encouragement. No consensus existed on the best shape for the blade or the most effective framework option. Designers were most notably stumped by how to build a pendulum that adjusted downward as the blade cut deeper into the stone.

Blackwell decided to build a device with two side posts, each studded with five holes drilled along its upper half, supported by a base and diagonal struts. A removable steel bar ran through opposite holes on the posts and could be set at different heights. In between the posts, the bar passed through an oval notch in the upper half of a long piece of wood — the pendulum. The notch is slightly longer than a dollar bill, giving the steel bar some leeway so the pendulum could move up and down freely while sawing.

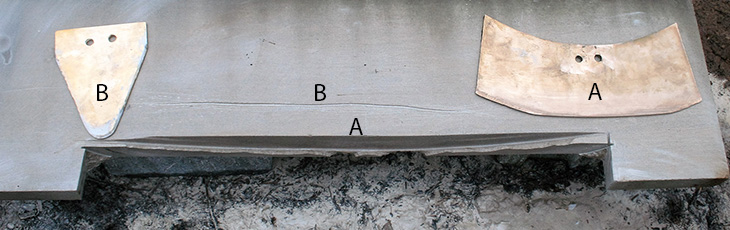

Finally, the apparatus needed a tough, sharp business end. A Greek archaeologist that Blackwell met while working at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens from 2012 to 2015 put him in touch with a metalsmith from Crete. The craftsman fashioned four bronze blades with different shapes for testing on the pendulum saw: a long, curved blade; a triangular blade with a rounded tip; a short, straight-edged saw and a long, straight-edged saw with rounded corners. During tests with each blade, Blackwell added water and sand to the limestone surface every two minutes for lubrication and to enhance the saw’s grinding power.

Blackwell suspected the triangular blade would penetrate the limestone enough to produce the best replicas of Mycenaeans’ arced cuts. He was wrong. Putting that blade through its paces, he found that only the tip creased the stone as the pendulum swung. The triangular blade yielded a shallow, wobbly groove that would have sorely disappointed status-conscious Mycenaean elites.

The short, straight blade did even worse. It repeatedly got stuck in the stone block during trials.

But in a dramatic showing, the long, curved blade left three concave incisions that looked much like saw marks at Tiryns. It took 45 minutes of sawing to reach a depth of 25.5 millimeters, a partial cut by Mycenaean standards. Blackwell and his brother-in-law took short breaks after every 12 minutes of pendulum pulling. “It takes a lot of physical effort to use a pendulum saw,” Blackwell says.

The elongated, straight blade with rounded corners proved easiest to use. It made one Mycenaean-like cut after only 24 minutes of sawing. Either the straight or the curved blade could have fit the bill for Mycenaean stoneworkers.

Close inspection of successful experimental cuts showed that Blackwell’s pendulum saw created curved incisions that were not segments of perfect circles. So an actual Mycenaean pendulum saw need not have been as tall as those earlier calculations had called for.

Blackwell suspects that Mycenaean masons tied or glued blades to one side of a pendulum’s arm. After sawing deep enough so that the pendulum’s wooden end hit rock, a worker chiseled and hammered off stone on one side of the incision so that the blade could be lowered for deeper sawing. Repeating those steps several times eventually left a flat face at the incision.

A half-finished pillar base from Mycenae preserves evidence of this procedure, Blackwell says. The stone displays a long, curved cut on a flat, vertical surface near one of its sides. The cut abruptly stops partway down. At that level, stone abutting the incision shows signs of having been pounded off.

Ghost saw

Even after Blackwell’s hands-on experiments, the Mycenaean pendulum saw remains an archaeological apparition. Some researchers believe it existed. Others don’t.

“Pendulum saws could have been a solution to Mycenaeans’ specific problem of having to work with conglomerate,” says archaeologist James Wright of Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania. Mycenaean conglomerate is considerably harder and more resistant to cutting than other types of rock that were available to the Mycenaeans and neighboring societies. Blackwell’s successful experimental incisions in limestone “conform with cut marks on Mycenaean stones,” Wright adds. The next step is to see how Blackwell’s pendulum saw performs on the tougher challenge of slicing through conglomerate.

While Blackwell’s experimental device produces Mycenaean-style curved cuts, that doesn’t mean Mycenaeans invented and used pendulum saws, contends archaeologist Jürgen Seeher of the German Archaeological Institute’s branch in Istanbul. Seeher built and tested the only other reconstruction of a pendulum saw.

In a 2007 paper published in German, Seeher concluded that there was a better option than his pendulum saw: a long, curved saw attached to a wooden bar and pulled back and forth by two people, like a loggers’ saw. A loggers’ saw could have produced curved marks on palace stones of ancient Hittite society, which existed at the same time as the Mycenaeans in what is now Turkey.

Unlike their Greek neighbors, Hittites did not construct pillars and gateways out of conglomerate. But a handheld, two-man saw would have enabled something a pendulum saw could not: precise cutting of conglomerate blocks from different angles, Seeher says.

“A handheld saw moved by two men is much more under control than a free-hanging pendulum,” he says.

Seeher has archaeological evidence on his side. Double-handled loggers’ saws have been excavated at sites from the Late Bronze Age Minoan society on Crete. Hittites and Mycenaeans, contemporaries of the Minoans, could easily have modified that design to cut stone instead of wood, Seeher proposes. They would have had to substitute rock-grinding straight edges for wood-cutting serrated edges.

Blackwell disagrees. He is convinced that Mycenaean craft workers trained for years to operate pendulum saws, just as skilled artisans like his dad go through a long apprenticeship to learn their trade. Mycenaeans may have worked in teams that took turns using pendulum saws to cut conglomerate into palace structures, he speculates. Those workers probably used highly abrasive emery sand from the Greek island of Naxos to amplify the grinding power of their swinging saws, Wright adds.

Blackwell worked with his own family team to create a rough approximation of what a Mycenaean pendulum saw may have looked like and how it was handled. His father’s construction expertise was crucial to the project. But those teenage summers doing scut work at building sites probably didn’t hurt, either.

This article appears in the April 28, 2018 issue of Science News with the headline, “Making the cut: Swinging blade slices into Bronze Age mystery.”