Hunter-gatherers first launched violent raids at least 13,400 years ago

Small-scale warfare began in the Stone Age, a new study suggests

Human skeletons previously unearthed at an ancient African cemetery, including this pair, display wounds indicating that they were victims of recurring raids more than 13,000 years ago. Pencils mark the locations of partial spear or arrow points and other stone artifacts found with the skeletons.

Courtesy of the Wendorf Archives of the British Museum

More than 8,000 years before the rise of Egyptian civilization, hunter-gatherers went on the attack in the Nile Valley.

Skeletons of adults, teens and children excavated in the 1960s at an ancient cemetery in Sudan known as Jebel Sahaba display injuries incurred in repeated skirmishes, raids or ambushes, say paleoanthropologist Isabelle Crevecoeur and her colleagues. The site, which dates to between 13,400 and 18,600 years ago, provides the oldest known evidence of regular, small-scale conflicts among human groups, says Crevecoeur, of the University of Bordeaux in France.

Although people buried at Jebel Sahaba don’t show signs of having fought in a one-time battle, they participated in an early form of sporadic warfare, the researchers conclude May 27 in Scientific Reports.

“Repeated violent episodes were probably triggered by well-recorded environmental changes” around the time people were buried at Jebel Sahaba, Crevecoeur says.

Signs of human activity declined sharply in the Nile Valley between around 126,000 and 11,700 years ago. Toward the end of that span, hunter-gatherers occupied floodplains in what’s now southern Egypt and northern Sudan. As the Ice Age waned, a fluctuating climate contributed to declines in prime fishing and hunting spots. Competition for those resources probably triggered fighting among regional groups, the researchers suspect.

The new report fits a scenario in which ancient, possibly culturally distinct communities violently raided each other when dwindling resources threatened their survival, says bioarchaeologist Christopher Stojanowski of Arizona State University in Tempe, who has studied the Jebel Sahaba remains but did not participate in the new study.

Ancient people carefully dug graves for their dead at Jebel Sahaba, interring bodies in similar, flexed postures. “So amidst the apparent hardship, amidst the apparent violence and tragedy, we still see humanity here,” Stojanowski says.

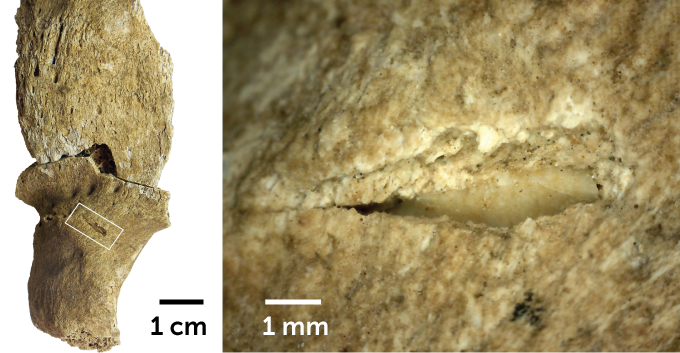

Out of 61 Jebel Sahaba skeletons held at the British Museum in London, 41 have at least one healed or unhealed injury, Crevecoeur and colleagues report. A majority of that damage was caused by stone spears, arrow points or close combat, the scientists say. Microscopic analysis also shows that 16 individuals had both healed and unhealed injuries, suggesting they had experienced repeated violent incidents during their lives.

Men, women and children from Jebel Sahaba display similar types and proportions of weapon wounds. That injury pattern more likely arose from periodic, indiscriminate raids rather than a single battle, in which the dead would have consisted mainly of male fighters, the researchers say.

Most of the 132 stone artifacts found in the Jebel Sahaba graves were pieces of the sharpened tips of spears or arrows, they say. Some of these finds were embedded in bones and bordered by damage created by hard impacts.

“Violence towards this community was truly extensive and indiscriminate in terms of age and sex,” says biological anthropologist Marta Mirazón Lahr of the University of Cambridge. Previously, she and colleagues reported skeletal evidence from a Kenyan site called Nataruk of a massacre of 12 hunter-gatherers between roughly 9,500 and 10,500 years ago (SN: 1/20/16).

An attack by a neighboring group best explains injuries on the Nataruk remains, Lahr says, which in her view were too scattered and broken up to have been intentionally buried. But Stojanowski and his colleagues contend that damage to and dispersal of some Nataruk bones could have been caused by soil compression after bodies were intentionally buried, probably at different times.

Researchers have long debated whether warfare originated among Stone Age hunter-gatherers or among state societies within roughly the past 6,000 years (SN: 7/18/13). Isolated fossil cases of violence and murder date back to around 430,000 years ago (SN: 5/27/15).

It’s hard to precisely estimate the frequency of violent attacks among ancient hunter-gatherers in Africa and elsewhere, says archaeologist Mark Allen of Cal Poly Pomona. The new Jebel Sahaba report suggests that competition for limited resources has long sparked lethal raiding among these groups, he says. Allen and his colleagues have found that skeletal evidence of violence among California hunter-gatherers from around 1,530 to 230 years ago peaked during times of resource scarcity.