Hurricane Maria’s death toll in Puerto Rico topped 1,100, a new study says

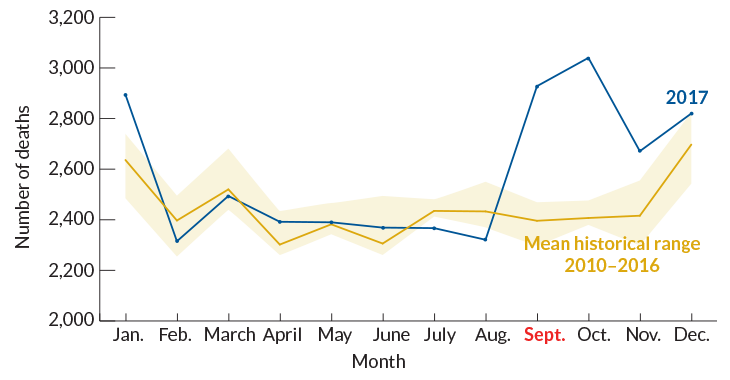

Analysis of vital statistics records shows spike in deaths in September and October of 2017

RIVER CROSSING A woman uses a cable line to get food and supplies across a river in the mountains around Utuado, Puerto Rico, in October of 2017. The community’s bridge was destroyed by Hurricane Maria.

U.S. Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Joshua L. DeMotts, USDA