Hyenas roamed the Arctic during the last ice age

Newly identified fossils confirm how the carnivores migrated to North America, researchers say

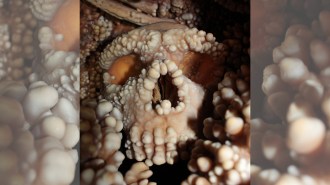

ARCTIC HYENAS New fossil evidence shows that hyenas lived in the Arctic during the last ice age, as depicted in this illustration.

Julius T. Csotonyi