If all goes according to Mike Dunne’s plan, the United States will build its first nuclear fusion power plant by the end of the next decade. Sixteen times a second, as the National Ignition Facility’s program director for laser fusion energy envisions it, a two-millimeter-wide capsule of cryogenic hydrogen will drop into a steel chamber and get zapped by a 384-beam laser. Matter will transform into energy, driving a turbine that injects up to a gigawatt of clean power into the electrical grid.

But all is not going according to plan. To be viable, a fusion power plant would need to generate more energy than it consumed. Yet except in nuclear weapons, scientists have never produced a fusion reaction that does that. For a half-century they have strived for controlled fusion and been disappointed, only to adjust their theories, retry and be disappointed again.

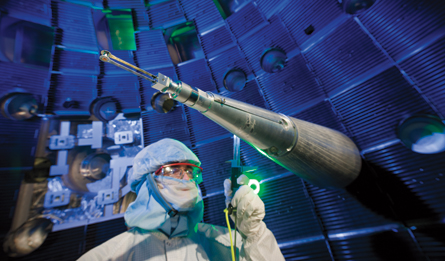

The $3.5 billion National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California was supposed to end that cycle of frustration. Computer simulations showed that firing 192 beams from the world’s most powerful laser at a hydrogen capsule would compress it within a millionth of a second to 1/40th its original diameter, the equivalent of shrinking a basketball to the size of a pea. The swiftness of that implosion would cause the hydrogen fuel to ignite in a brief, self-sustaining fusion reaction releasing a helium nucleus, a neutron — and up to 100 times as much energy as the laser delivered.

In 2009, NIF officials confidently stated that by September 30, 2012, they would demonstrate a fusion reaction producing net energy, a milestone known as ignition. That deadline has come and gone. The laser works just as physicists hoped it would, delivering a powerful punch right where it was supposed to go. But ignition failed. For reasons scientists still can’t explain, the simulations were off the mark. Crushing an already minuscule sphere of hydrogen into a perfectly round speck turns out to be unexpectedly tough.

“Nature just wants to break you,” says John Edwards, NIF’s associate director of fusion.

Now he and other officials fear that the difficulty of shrinking a little ball of hydrogen could derail their laser fusion dream. Their new goal is just to figure out if laser ignition is achievable at NIF or at any future facility.

If not, then the only foreseeable hope for fusion power lies in ITER, a $20 billion facility under construction in France that uses magnets instead of lasers to induce fusion. Though saddled by their own logistical and financial obstacles, ITER physicists hope to achieve ignition and start work on a magnet-based fusion power plant by the late 2020s.

The next few years will be pivotal in determining whether NIF’s laser approach is even an option for energy production, or whether all hopes for fusion will turn overseas to ITER.

“We don’t know what it is going to take to get ignition,” says Kirk Levedahl, the program manager for NIF’s ignition effort at the U.S. Department of Energy.

Star power

NIF’s slogan is “Bringing Star Power to Earth,” but that is a rather grandiose description of what the facility was built to do. The sun’s gravity is so great that the energy output from one second of nuclear fusion in that gargantuan star would, if converted into electricity, satisfy the planet’s needs for a million years. No machine is ever going to compete with that.

NIF was designed to be the next best thing: a facility that could, on a very small scale, achieve starlike conditions and stimulate fusion for fractions of a second at a time. In lieu of the gravity, NIF would use the world’s most powerful laser to compress a peppercorn-sized capsule of hydrogen fuel into a hot, dense ball 1/60,000th its original volume. Inside that tiny sphere, a cascade of fusion reactions would release many times more energy than the laser delivered.

Prior to 2009, physicists had never used a laser with even a hundredth the energy of NIF’s. They had never studied matter packed into a ball as hot and dense as the sun’s core. An external review panel warned that “substantial scientific challenges remain to achieving ignition.” Yet NIF officials were confident enough to put a stake in the ground and claim that they would ignite a capsule by September 2012. “I think we’ll get ignition relatively shortly after we turn the facility on,” said George Miller, then-head of Livermore, at NIF’s dedication ceremony in 2009.

A lot of that confidence came from computer simulations. These were no video game–like approximations of reality. Each simulation consisted of more than a million lines of code filled with numbers and equations describing every push and pull that nuclei in the fuel capsule would encounter once the laser fired. All the data included in the simulations were based on well-tested theories and rigorous experiments, including measurements from hundreds of thermonuclear bomb explosions. The world’s fastest supercomputers required days or weeks to spit out the results.

Many of these simulations predicted that NIF’s 192-beam laser would comfortably achieve ignition. They showed that a short, powerful laser pulse coming from all directions would compress the pellet enough to create heat and pressure more intense than that in the sun’s core, forcing hydrogen nuclei together to form high-energy helium nuclei and neutrons.

The payoff hinged on the fate of the newly formed helium nuclei, which would jet out from the center of the capsule in all directions. If the capsule compressed as the simulations predicted, then the helium would not be able to escape. Similar to running through a dense forest in the dark, it would have a very good chance of slamming into a tree — or, in this case, a hydrogen nucleus. Each of those collisions would create heat, which in turn would encourage more hydrogen to fuse, thus producing more helium. Fusion would briefly become self-sustaining, leading to a huge jump in the energy produced.

It all sounded good, but the scientists involved were cautiously optimistic. They knew that any simulation is only as good as the information that goes into it. “Everyone knew this was an extrapolation beyond what we believed we could extrapolate to,” Levedahl says. “But it was the best we could put together at the time.”

A hard slog

In September 2010, prognostication finally yielded to experimentation. Physicists fired the NIF laser at a centimeter-long metal cylinder called a hohlraum. The quick pulse stimulated the hohlraum to emit X-rays, which bombarded the plastic-coated hydrogen fuel capsule stored inside. The capsule’s coating vaporized and exploded, triggering a rocket effect that sent the hydrogen hurtling inward.

All those steps went according to plan. But strange things happened once the capsule began to collapse. Instead of remaining spherical, as the simulations predicted, the capsule warped into an amorphous blob. Physicists had designed NIF with 192 laser beams fired from all directions specifically to preserve the capsule’s symmetry as it imploded; yet the compressed capsules looked more like water balloons getting squeezed by two hands.

During other trial runs, a capsule would start to compress symmetrically, but then little bumps would emerge on its surface. As the implosion continued, these minor imperfections grew exponentially. Little hills on the capsule’s surface became mountains. Gently sloped troughs morphed into steep valleys. Within billionths of a second what began as a perfectly smooth ball looked more like a medieval knight’s spiky mace.

These confounding early experiments clearly revealed that ignition was not going to be handed over on a silver platter. “The results told us it was going to be a really hard slog,” Levedahl says.

Physicists quickly shifted their plan. Throughout 2011 and early 2012, when many of them had expected they would be on the cusp of ignition, they were simply trying to figure out what was going wrong. They designed custom targets and installed monitoring equipment to probe specific properties of the implosion.

NIF physicists determined that the X-rays released by the zapped hohlraum were not compressing the capsule inside evenly. In addition, the warped capsule sometimes fractured as it collapsed, allowing cold particles on the outside to mix with the hot stuff inside and short-circuit any fusion reaction.

In response, the NIF team tweaked the design of the hohlraum and redirected the beams slightly to trigger a more symmetrical response. The physicists also tuned the laser pulse so it would deliver the optimal force to kickstart compression of the fuel shell. By mid-2012, NIF had made considerable progress in imploding the capsules, compressing them more while maintaining a spherical shape.

Even so, ignition was not even close to attainable when the September 2012 deadline arrived. The highest energy output achieved to that point, according to a December report, was at most a third of the amount needed to trigger the helium collisions that would ignite the fuel.

Facing the unexpected

Walking through the Livermore campus, a former training ground for World War II Navy pilots, it is hard to tell that NIF has missed the mark. A giant “Bringing Star Power to Earth” banner hangs on the outside of the main complex. Scientists seem upbeat, eager to overcome the curveballs fusion keeps throwing them.

That’s because generally, physics is as much about being wrong as it is about being right. Physicists want their theories to be as accurate as possible, but they also know their theories are incomplete. Identifying unexpected phenomena is the key to constructing even better theories.

NIF director Edward Moses points to another record-setting facility: the Large Hadron Collider in Europe, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator. The machine’s main goal was to observe a particle called the Higgs boson. The Higgs is an essential element of the Standard Model, a leading theory that describes every particle and force in the universe. On July 4, 2012, physicists proudly announced that they had found it.

But since then the LHC physicists’ excitement has dimmed considerably. Yes they discovered the Higgs, but so far the particle looks exactly like the theory said it would. The experiment affirmed the Standard Model, but unless anything strange turns up, physicists won’t be able to add to and improve the theory. NIF physicists wish their simulations were better; LHC physicists complain that theirs were too good.

“Mother Nature has been very cruel,” says LHC physicist Steve Blusk of Syracuse University, in a statement awfully reminiscent of Edwards’ “Nature wants to break you” complaint.

While the pace is frustrating, NIF’s problems are helping physicists understand how matter behaves in environments hotter and denser than the core of the sun (SN: 1/14/12, p. 26). The things they learn will then be incorporated into the simulations, Moses says, giving them better predictive power. Still, his comparison of the two multibillion-dollar facilities only goes so far. The LHC was built to learn fundamental things about the universe, but NIF was built to achieve ignition. “There’s a whole different dynamic for fusion,” Moses says.

Fusion’s eternal future

Fusion ignites furious debate as few other scientific endeavors can. Advocates point out that fusion packs the highest punch of any known energy-generating process, with one gram of hydrogen fuel possessing the same energy content as 13.5 metric tons of coal. The fuel is readily available, there are no radioactive or environmentally hazardous waste products, and there is no risk of nuclear meltdown.

Opponents argue that fusion is impractical and overwhelmingly expensive to achieve. Just consider the frustrating history of physicists’ attempts to harness the process.

The quest began with the first demonstration of fusion in a nuclear weapon. In 1952, Manhattan project scientists Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam developed a thermonuclear weapon that was essentially two bombs in one — a runaway fission reaction emitted X-rays that compressed a canister of hydrogen atoms and forced them to fuse, releasing energy equivalent to millions of tons of TNT.

In the late 1950s Livermore physicist John Nuckolls used the bomb as inspiration for a peaceful application of fusion power. He realized that if he significantly scaled down the size of the hydrogen canister, he could induce fusion without the need for a fission spark plug. He envisioned a small capsule of hydrogen placed inside a hohlraum. If the hohlraum were zapped with a substantial (but not nuclear-sized) burst of energy, it would emit X-rays that would implode the hydrogen, much like in the bomb.

Getting started — again

The laser, invented in 1960, seemed to be the perfect delivery mechanism to start the fusion process rolling. Beginning in 1974, Lawrence Livermore marched out a parade of lasers — Janus, Cyclops, Argus, Shiva — to test Nuckolls’ idea. With laser technology in its infancy, scientists were mainly focused on improving the reliability and integrity of the laser shots. Then came Nova, a 10-beam laser at Livermore built in 1984 to achieve ignition. While many computer simulations predicted Nova would succeed, it never came close.

The quest for laser fusion may have stopped there if not for President Bill Clinton. In 1993 he announced his support for a comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty and ordered the Department of Energy to find ways to maintain the nuclear stockpile without detonating any bombs. Building a laser facility to achieve ignition could test components of the nuclear arsenal sans explosions — after all, Nuckolls’ original idea was based on the architecture of H-bombs. NIF was conceived as a defense project, overseen by the National Nuclear Security Administration, that just so happened to benefit fusion energy research.

The downside of this defense-energy relationship is that it added yet another stigma to an already controversial line of research. When NIF failed to meet the ignition deadline last September, NNSA noted that the facility had nonetheless resolved several nagging physics questions regarding the U.S. nuclear stockpile. That’s probably good news for the U.S. military, but it’s impossible to say for sure because the details are classified. The public data, on the other hand, are not very encouraging, especially to politicians who have to justify NIF’s multi-billion-dollar price tag.

NIF physicists feel the pressure but defend their track record. “There’s been an enormous amount of progress,” says Alex Hamza, who leads production of NIF’s hohlraum targets. “I don’t think the outside community understands that.”

Recent reports released by NNSA, the University of California and the National Research Council agree with Hamza’s assessment. They cite the researchers’ steady progress since their first disastrous laser shots as proof that NIF can proceed further toward ignition. But reports also conclude that the compression problems may be too much for NIF and perhaps any facility. NNSA’s stated goal is no longer to achieve ignition but rather, by September 2015, to determine whether achieving it is even possible with NIF’s approach. At the same time, the agency has reduced the number of laser shots dedicated to ignition in favor of more weapons and basic science research.

The NRC recommends that fusion scientists hedge their bets, calling for increased study of alternative laser and target designs. The Omega laser at the University of Rochester in New York, for example, is testing an approach to fire on the hydrogen pellet directly rather than on a hohlraum. Livermore officials had hoped that the rapid achievement of ignition would allow scientists and politicians to rally around NIF’s laser fusion approach; instead, resources are being spread around in a desperate attempt to find other promising approaches to imploding hydrogen fuel. “The fact is that we don’t have any predictive capability right now,” says Steve Cowley, a fusion physicist at Imperial College London who contributed to the NRC review. “Any progress is going to be a guess. But that’s why you take measurements: It allows you to understand what to do next.”

Cowley also points out that using a laser is not the only way to strive for fusion. Many physicists favor ITER’s alternative approach of using powerful magnets to heat and confine hydrogen plasma, though that approach has its own history of expensive disappointments. Six countries plus the European Union are spending $20 billion on the project. With so much money at stake between NIF and ITER, the next decade could very well determine the fate of fusion energy.

That uncertainty still isn’t stopping Mike Dunne. He continues plotting his prototype fusion power plants, optimistic that he will get the chance to put his plan into action. “I never trust plasma physicists’ ability to project the future,” he says. “But I’m confident they’ll come through soon.”