A space rock named Kamoʻoalewa (illustrated drifting above the moon, with Earth in the background) may be a fragment of lunar material that broke off in an ancient cratering event.

ronib1979/iStock/Getty Images Plus

The moon’s violent history is written across its face. Over billions of years, space rocks have punched craters into its surface, flinging out debris. Now, for the first time, astronomers may have spotted rubble from one of those ancient smashups out in space. The mysterious object known as Kamoʻoalewa appears to be a stray fragment of the moon, researchers report online November 11 in Communications Earth & Environment.

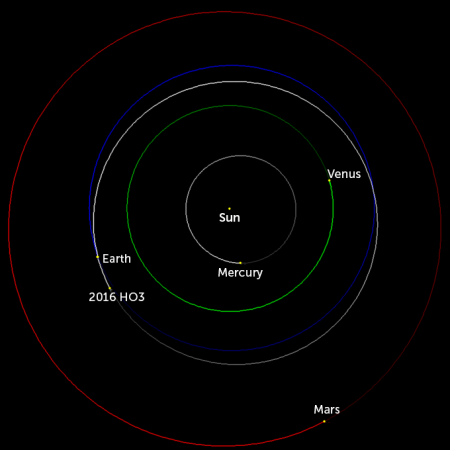

Discovered in 2016, Kamoʻoalewa — also known as 2016 HO3 — is one of Earth’s five known quasisatellites (SN: 6/24/16). These are rocks that stick fairly close to the planet as they orbit the sun. Little is known about Earth’s space rock entourage because these objects are so small and faint. Kamoʻoalewa, for instance, is about the size of a Ferris wheel and strays between 40 and 100 times as far from Earth as the moon, as its orbit around the sun weaves in and out of Earth’s. That has left astronomers to wonder about the nature of such tagalong rocks.

“An object in a quasisatellite orbit is interesting because it’s very difficult to get into this kind of orbit — it’s not the kind of orbit that an object from the asteroid belt could easily find itself caught in,” says Richard Binzel, a planetary scientist at MIT not involved in the new work. Having an orbit nearly identical to Earth’s immediately raises suspicions that an object like Kamoʻoalewa originated in the Earth-moon system, he says.

Researchers used the Large Binocular Telescope and the Lowell Discovery Telescope, in Safford and Happy Jack, Ariz., respectively, to peer at Kamoʻoalewa in visible and near-infrared wavelengths. “The real money is in the infrared,” says Vishnu Reddy, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Light at those wavelengths contains important clues about the minerals in rocky bodies, helping distinguish objects such as the moon, asteroids and terrestrial planets.

Kamoʻoalewa reflected more sunlight at longer, or redder, wavelengths. This pattern of light, or spectrum, looked unlike any known near-Earth asteroid, Reddy and colleagues found. But it did look like grains of silicate rock from the moon brought back to Earth by Apollo 14 astronauts (SN: 2/20/71).

Ring around the sun

Kamoʻoalewa, also known as 2016 HO3, has an orbit (white) that is nearly identical to Earth’s (blue), causing the object to weave around Earth as it circles the sun.

Kamoʻoalewa and Earth’s similar orbits

“To me,” Binzel says, “the leading hypothesis is that it’s an ejected fragment from the moon, from a cratering event.”

Martin Connors, who was involved in the discovery of Earth’s first known quasisatellites but did not participate in the new research, also suspects that Kamoʻoalewa is a chip off the old moon. “This is well-founded evidence,” says Connors, a planetary scientist at Athabasca University in Canada. But, he cautions, “that doesn’t mean it’s right.”

More detailed observations could help confirm Kamoʻoalewa is made of moon stuff. “If you really wanted to put that nail in the coffin, you’d want to go and visit, or rendezvous with this little quasisatellite and take a lot of up-close observations,” says Daniel Scheeres, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder not involved in the work. “The best would be to get a sample.”

China’s space agency has announced plans to send a probe to Kamoʻoalewa to scoop up a bit of rock and bring it back to Earth later this decade.