Kidney stones grow and dissolve much like geological crystals

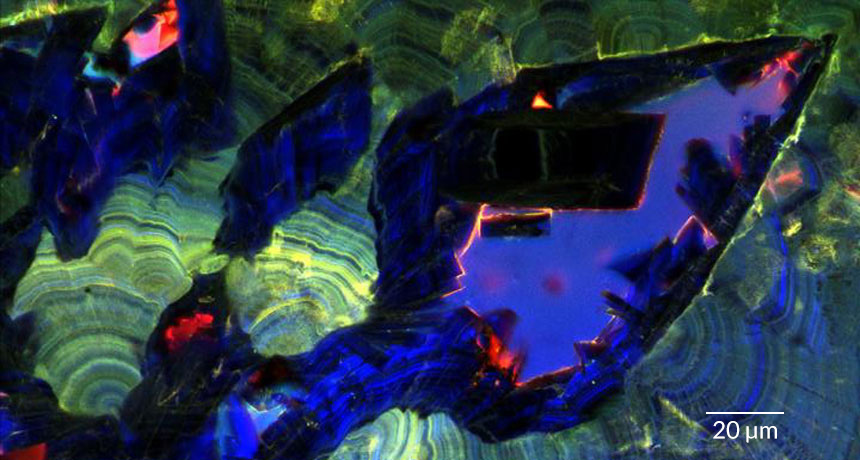

The minerals grow in layers interspersed with areas where the stone has dissolved

JEWEL BOX Shining ultraviolet light on this thin slice of a kidney stone reveals layers of crystal growth (green and light blue) interspersed with large gemlike structures (dark blue) that show where the stone has dissolved and regrown.

Mayandi Sivaguru and Jessica Saw/Bruce Fouke Lab/Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology/Univ. of Ill.