Lost-and-found dinosaur thrived in water

Fossils pieced together through ridiculous luck revise view of Spinosaurus

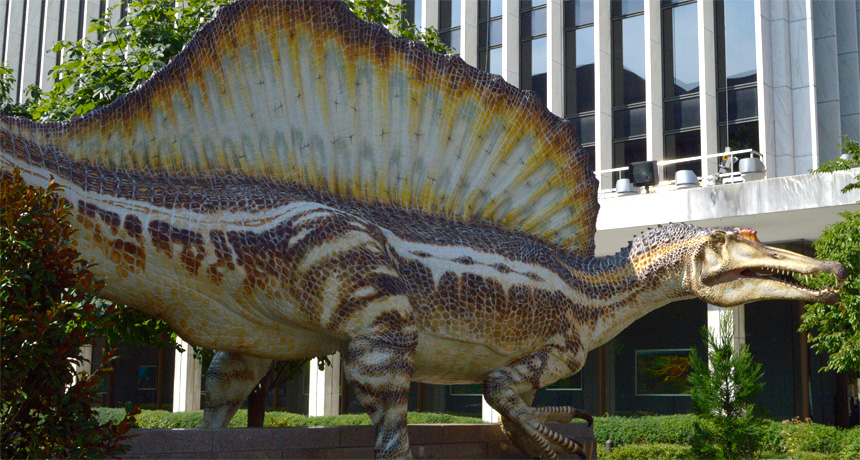

SPLASHIEST DINO Sail-backed Spinosaurus was unique among known dinosaurs for its water-adapted body, and four-legged gait on land, as demonstrated by a sculpture in the National Geographic Society’s courtyard in Washington, D.C.

Bryan Bello/Science News

Fossils brought together by unlikely chances now suggest that the sail-backed Spinosaurus was no mere wade-in-the-water fish-catcher. Instead, it is the only known dinosaur that routinely took to the water.

Plenty of big reptiles plied prehistoric waters, but they weren’t dinosaurs. Some dinos clearly ate fish, but that doesn’t mean they swam much.

Now bones of a Spinosaurus traced to a freelance fossil digger’s trove in Morocco have inspired a new look at the 15-meter-long predator, which was first described in 1915. Rising from the beast’s back was a bony flap as tall as a human being. The Morocco finds, plus a digital model based on them and other fossil material, show that the species was “the first dinosaur with unmistakable adaptations for a life spent to a large extent in water,” says Nizar Ibrahim of the University of Chicago.

Other researchers are excited by the find. “An extinct animal that we already thought was kind of weird was actually even stranger,” says paleontologist Lawrence Witmer of Ohio University in Athens, after looking over the new paper. And paleontologist Stephen Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh says, “This was a dinosaur that hunted sharks, which is about as cool as it gets.”

In 2009, Ibrahim was stunned to visit researchers at the Natural History Museum in Milan and see recently acquired Spinosaurus bones. The researchers had no information on where the bones had been excavated, so they weren’t of great use to science. But the sight jogged Ibrahim’s memory of a man in the desert with a cardboard box.

On one of Ibrahim’s earlier fossil expeditions to Morocco, a local man had shown him a box with some sediment-caked, hard-to-identify fossils, including one with the same cross section as some of the Spinosaurus bones in Milan. Ibrahim had had the stranger’s fossils deposited in a Moroccan museum. But he didn’t have even the name of the man who had approached him. He could say only that the stranger was probably somewhere in the Sahara and had a mustache.

Revisiting the Moroccan town where he had met the fossil source and asking around yielded nothing. “I saw all my dreams going down the drain,” Ibrahim says. Then, sipping mint tea in a café, he glimpsed the mustached man just walking by.

Ibrahim persuaded the digger to reveal his site, where more Spinosaurus fragments turned up. It lay in Morocco’s Kem Kem region in rock about 97 million years old. A vast water network there had once nourished coelacanths, sharks, crocodile-like predators and dinosaurs.

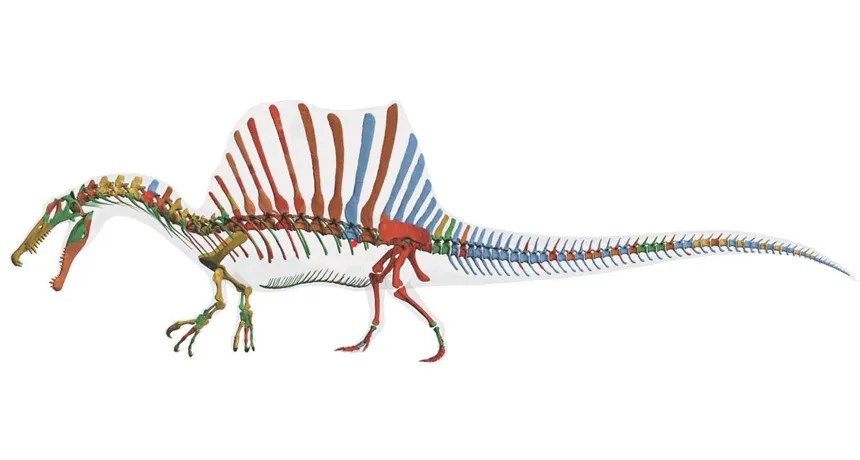

The partial Spinosaurus skeleton from that site had dense limb bones, the researchers report September 11 in Science, like the bones of penguins, manatees and other animals that evolved aquatic life from terrestrial ancestry. Having dense bones helps formerly land-dwelling animals control their buoyancy.

Also, the pelvis was small for the Spinosaurus’ size and its hind limbs were short and muscular. Ibrahim compares them to bones of early whale species losing their adaptations for walking on land.

Spinosaurus still had the ability to move on land “and would have been a fearsome animal,” says coauthor Paul Sereno, also at Chicago. Yet features such as the unusual hindquarters and a center of mass a bit more forward than in two-legged dinosaurs suggest Spinosaurus walked on all fours, the researchers say. (Brusatte cautions that it’s not easy to estimate center of mass based just on a skeleton.) Spinosaurus would have been the only known dinosaur among the T. rex-style predator group of theropods to use four legs instead of two, the researchers say.

The arguments that Spinosaurus spent much of its time in water are “generally very compelling,” Witmer says, though he’s not fully convinced on some points. The researchers report Spinosaurus nostrils lying well back from the snout tip as a possible adaptation to a watery life. Yet, Witmer says, modern crocs, hippos and seals have nostrils at their snout tips despite their watery habits.

Hippos do much of their traveling in water by walking on the bottom, says vertebrate paleontologist Casey Holliday of the University of Missouri in Columbia. So he wonders whether Spinosaurus mostly swam or walked. “The dino doggy paddle I’m not sure about,” he says.