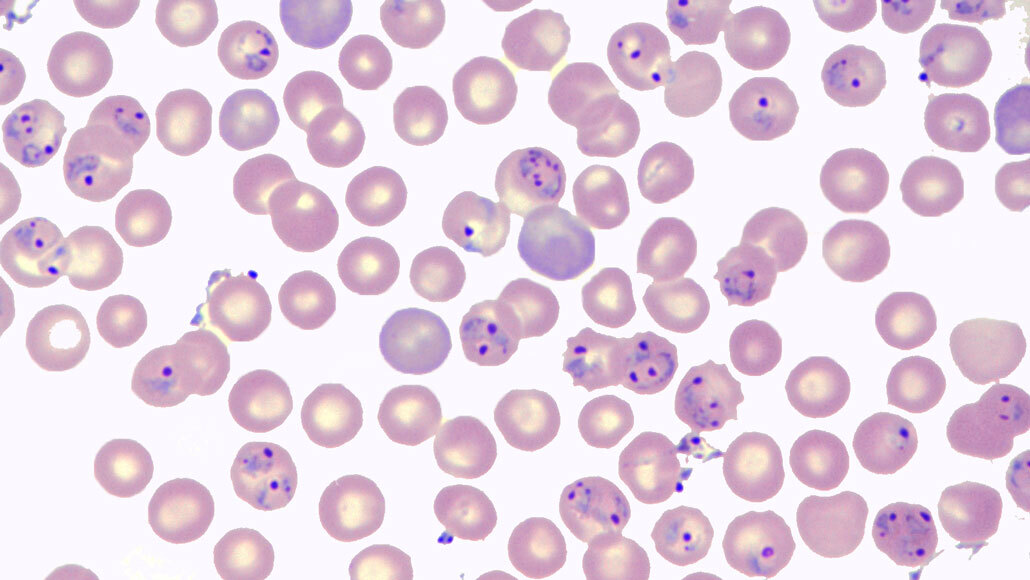

Malaria parasites (purple) infect hosts’ red blood cells (pink, with mouse cells shown). Scientists have now discovered that these parasites have an internal circadian clock, which could help explain why hosts experience rhythmic fevers.

Joseph Takahashi Lab/UT Southwestern Medical Center/HHMI

The parasites that cause malaria may march to the beat of their own drum.

New genetic analyses suggest that Plasmodium parasites possess their own circadian rhythms, and don’t depend on a host for an internal clock, researchers report May 15 in Science. Figuring out how Plasmodium’s clock ticks may lead to ways to disrupt it, potentially adding to the growing arsenal of treatments for malaria (SN: 11/27/13). In 2018, the mosquito-borne illness sickened an estimated 228 million people worldwide and caused more than 400,000 deaths.

A malarial infection is a series of cyclical symptoms. Depending on the Plasmodium species involved, fever and chills return roughly every 24, 48 or 72 hours, thanks to the parasites’ synchronized reproduction within and destruction of a host’s red blood cells.

Researchers had long thought that the rhythmic nature of an infection was likely driven by a host’s circadian rhythms, says molecular parasitologist Filipa Rijo-Ferreira, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute associate at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Circadian clocks help organisms anticipate regular, cyclic changes in their environment, like day and night cycles and daily fluctuations in temperature. These clocks are made up of genes and proteins that drive daily rhythms (SN: 10/2/17), such as the release of hormones, and typically operate on 24-hour cycles in many animals.

Rijo-Ferreira and colleagues recently showed that the Trypanosoma parasite behind the illness known as sleeping sickness has its own internal clock. So the team decided to look for a similar ability in Plasmodium.

The scientists tracked rhythms of how genes were turned on and off in malaria parasites in infected mice hosts. The researchers put some mice in constant darkness, eliminating day and night cues and throwing off the animals’ circadian rhythms. But the timing of changes in the parasites’ gene activity levels in those mice was similar to that of mice exposed to regular day-night cycles.

Next, to see if the parasites used a host’s feeding schedule to orient their clock, the team provided mice with food spread evenly throughout the day. But the Plasmodium in those mice kept the same internal rhythms as those in mice that were fed once daily.

And when the parasites were in hosts engineered to lack a clock entirely, the pathogens’ timekeeping ability ticked right along unhindered. These findings reveal that the light and feeding cues that set the hosts’ clocks don’t affect parasites’ rhythms, suggesting that the parasite has its own independent clock.

What’s more, in mutant mice genetically engineered to have a circadian clock slightly longer than 24 hours, the parasites attempted to synchronize their own clocks to that of their host’s, slowing their pace. While malaria parasites can parallel their host’s schedule, they don’t depend on their host for a clock, the team concludes, suggesting that the parasites use their own clocks to align with the host’s during an infection.

But while individual Plasmodium parasites appear to have an internal clock independent of a host’s, syncing up all the clocks in a population of parasites inside of a host does apparently require input from the host’s rhythms, the researchers say. In mice lacking an internal clock, the synchrony within an entire parasite population slowly decayed, falling apart after eight or nine days. This is similar to what happens to internal clocks in groups of mammalian cells without any external cues, such as sunlight or chemicals.

“That is quite reassuring, because we really think that [Plasmodium’s clock] behaves just as another circadian system that we know very well,” Rijo-Ferreira says.

Rijo-Ferreira says she wasn’t surprised by the findings, given how many times internal clocks have independently evolved in nature in organisms ranging from bacteria to fungi to animals. “It’s almost unbelievable that an organism wouldn’t have a clock,” she says.

Further support for Plasmodium’s internal clock comes from a separate study, also in the May 15 Science, led by molecular biologist Steven Haase at Duke University. Haase and his team isolated a species of Plasmodium entirely from a host, growing four different strains of the parasite in the lab. They tracked the parasites’ patterns of gene activity levels too, finding that as much as 92.6 percent of the known genes for Plasmodium appear to be clock controlled, keeping time in the absence of a host.

Now that the existence of some kind of clock is confirmed, Haase says, the next steps are revealing its molecular underpinnings, and how the clock interacts with that of the host.

Uncovering “the components of the parasite’s timekeeping mechanism” could help determine if, in fact, the parasites have their own independently and consistently ticking clock, says Sarah Reece, an evolutionary parasitologist at the University of Edinburgh not involved with either study. While the findings suggest that some form of clock is at work here, “it’s still possible [the parasites] keep time in a simpler way,” she says, for instance reacting to some other external stimuli.