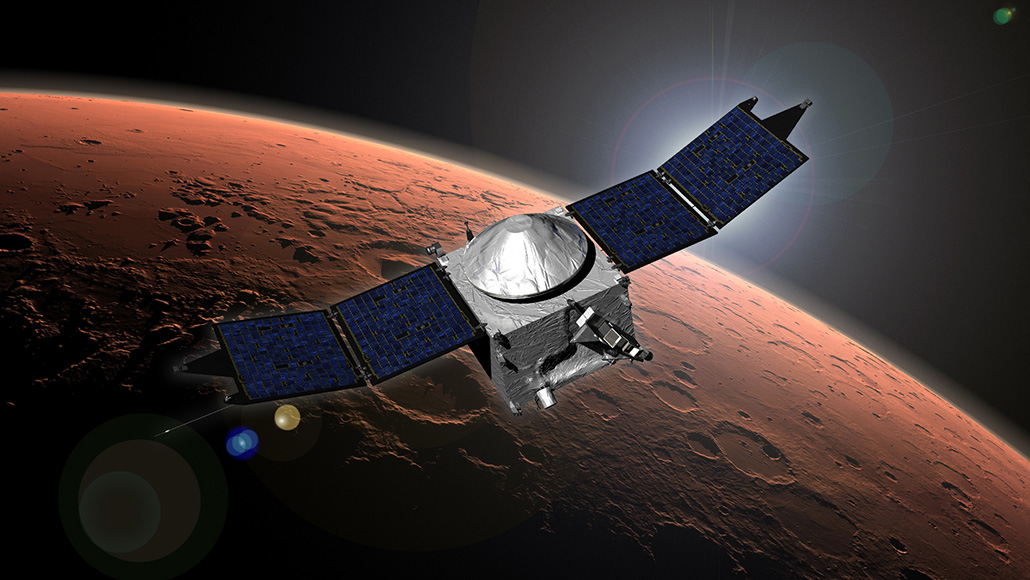

Data from NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft (illustrated) have let researchers piece together the first-ever maps of wind circulation in the upper atmosphere of Mars.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

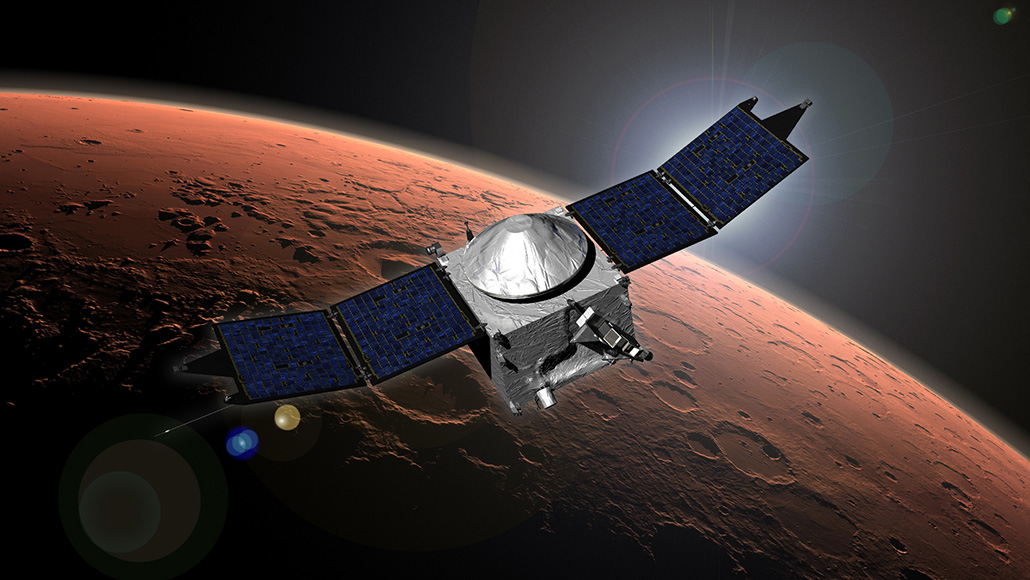

Data from NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft (illustrated) have let researchers piece together the first-ever maps of wind circulation in the upper atmosphere of Mars.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center