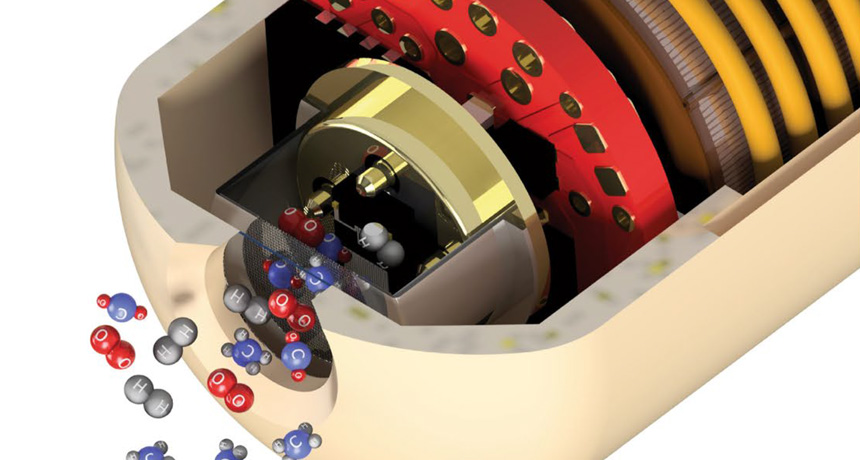

GUT CHECK A plastic capsule containing instruments to sense various gut gases (illustrated) could help diagnose or monitor treatments for gastrointestinal problems.

K. Kalantar-Zadeh et al/Nature Electronics 2018

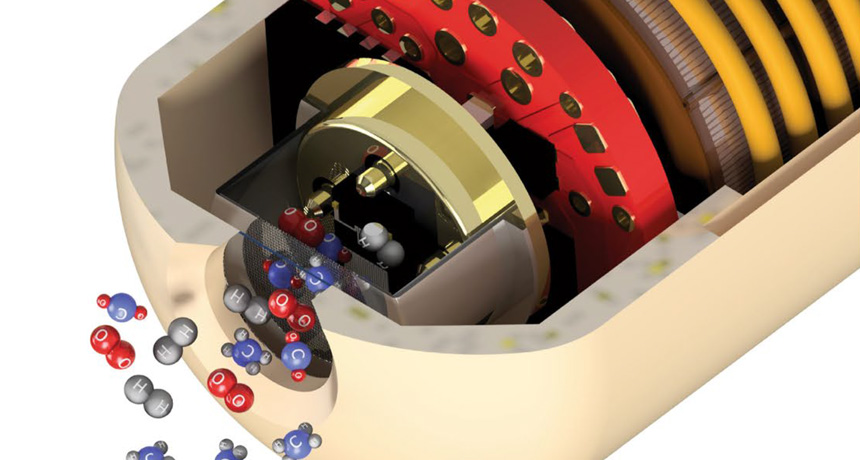

GUT CHECK A plastic capsule containing instruments to sense various gut gases (illustrated) could help diagnose or monitor treatments for gastrointestinal problems.

K. Kalantar-Zadeh et al/Nature Electronics 2018