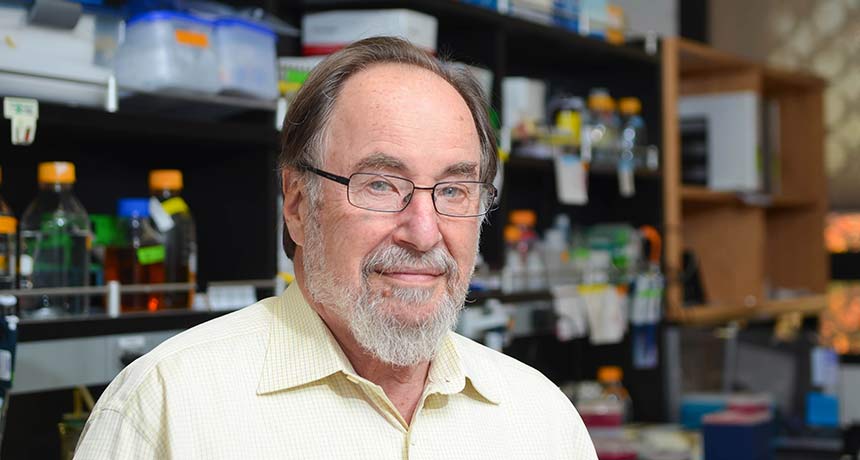

NO BAN Nobel laureate David Baltimore is a proponent of doing research to make human gene editing safer, but says the technique isn’t ready for producing genetically modified babies. He talked with Science News about how gene editing should be regulated.

Caltech

Scientists are vigorously debating how, and if, they can put the human gene-editing genie back in the bottle.