Planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres could harbor life

Lab experiments show that yeast and E. coli survive and reproduce in hydrogen-rich conditions

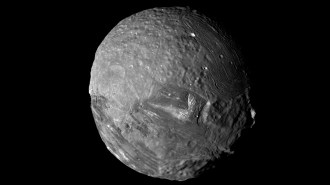

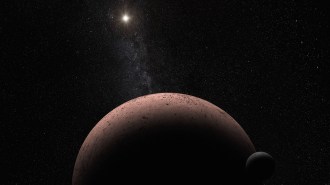

Life on an inhabited exoplanet (one possibility illustrated here) would emit gases that could build up in the atmosphere, where astronomers on Earth can detect them. New work shows an atmosphere made entirely of hydrogen would be worth checking for those biosignatures.

Mark Garlick/Science Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

Microbes can live and grow in an atmosphere of pure hydrogen, lab experiments show. The finding could widen the range of environments where astronomers seek signs of alien life.

“We’re trying to expand people’s view of what should be considered a habitable planet,” says exoplanet astronomer Sara Seager of MIT (SN: 10/4/19). “It seems to increase our chances that we may find life elsewhere.”

Seager and her colleagues placed yeast and E. coli — both considered stand-ins for other single-celled organisms — in small bottles with some nutrient broth. The researchers displaced the air in six bottles and replaced it with pure hydrogen gas, pure helium gas or a mixture of 80 percent nitrogen and 20 percent carbon dioxide. A final set of bottles was left with Earth air.

Every few hours, the researchers removed some of the microbes with a hypodermic needle to count how many were alive. The microbes had replicated in every atmosphere tested, the team reports May 4 in Nature Astronomy, thriving most in ordinary Earth air.

In addition, E. coli in particular produced several gases that already are considered potential biosignatures, or signs of possible life, if found in other planets’ atmospheres, including ammonia, methanethiol and nitrous oxide (SN: 4/18/16).

“E. coli is such a simple organism, yet it produces an incredible array” of gases, says astrobiologist Giada Arney at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., who was not involved in the experiments. “Knowing which gases can be produced by life is a necessary first step towards vetting them as possible detectable biosignatures on an exoplanet.”

But just seeking a hydrogen-rich atmosphere isn’t enough, says astrobiologist John Baross of the University of Washington in Seattle. A planet would also need to have the equivalent of the nutrient broth in the bottle for life to thrive — perhaps a liquid water ocean that exchanges chemicals with a rocky surface.

Astrobiologists plan to search for signs of alien life by looking at starlight filtering through exoplanets’ atmospheres (SN: 4/19/16). If life on a rocky planet’s surface emits telltale gases, future telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope could detect those emissions.

It’s not clear whether rocky planets with pure hydrogen atmospheres exist. Based on what’s known about how planets form, pure hydrogen atmospheres should be rare, says planetary scientist Daniel Koll of MIT, who was not involved in the new work.

Because hydrogen is so light, an atmosphere of all or mostly hydrogen would be puffier and extend up to 14 times farther from the surface than Earth’s nitrogen-dominated atmosphere. That means more starlight would filter through the atmosphere on its way to Earthly telescopes, making it easier to probe those atmospheres for biosignatures.

While the results also confirmed the microbes could also live in helium and nitrogen-dominant atmospheres, these atmospheres would be thinner and therefore harder to detect around other planets.

Seager noted the simple experiments might not be surprising to biologists. After all, there are microbes living in hydrogen-rich environments on Earth, such as niches in mines where calcium decay can create air pockets with 33 to 88 percent hydrogen by volume. (Most of Earth’s hydrogen is locked up in water; the atmosphere overall contains much less than 1 percent hydrogen gas.)

Also, both E. coli and yeast can survive without oxygen — E. coli can live in the guts of many animals, and yeast is used in the fermentation industry for brewing beer. But since neither microbe is adapted to a purely hydrogen environment, Seager thought it was worth testing.

Koll agrees. “This is a very in-your-face demonstration that if Earth life can exist under hydrogen atmosphere conditions, then certainly alien life should be able to,” Koll says. “We shouldn’t limit, or be too Earth-centric, in what we consider interesting when we study other planets.”

He adds that, if life-forms complex enough to have lungs and voice boxes lived on these worlds, they would have squeaky, high-pitched voices.

“You know the effect where you inhale a helium balloon and your voice sounds like Mickey Mouse?” he says. Hydrogen does the same thing. “You could definitely travel to an alien planet, take one breath of air, say something with a squeaky voice, and put your helmet back on.”