Reading the patterns of spatial memories

Brain imaging alone accurately predicts a person’s location in a virtual room

Harry Potter had it easy: All he had to do to see another wizard’s memories was peer into that wizard’s swirling pensieve. Mind-reading is not so simple for everybody else. But a new study reveals that even those without magical gadgets may one day “see” someone else’s memories.

In the study, which appears online March 12 in Current Biology, researchers used patterns of brain activity to accurately predict where someone was standing in a virtual room.

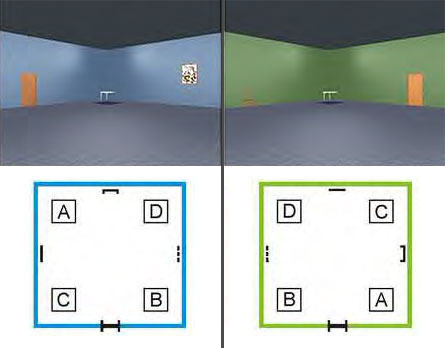

Each of four study participants sat down to a computer and toured a large virtual room. The room contained objects that helped volunteers get oriented, including clocks, chairs and pictures. As participants navigated through the virtual space, brain cells preserved the memory of the route taken to the final location (“turn left at the picture of the boat”).

Once participants reached their destinations, they stared at blank virtual floor for five seconds. Only then did the researchers measure brain activity with fMRI, to ensure that the measured brain activity stemmed from the memories of getting to the location and not from thoughts associated with any particular object in the virtual room. “Because the floor was identical at each target location, then the only thing we could have been decoding was the spatial location,” explains Eleanor Maguire of University College London, a coauthor of the study.

Specific parts of each participant’s hippocampus were active after that person had navigated to particular places in the room. A few practice rounds provided fodder for creating algorithms for each participant that correlated different brain activity patterns with different virtual locations. The algorithms, the team found, could in turn “predict” new virtual locations, not those used during practice rounds, based on each person’s pattern of brain activity.

Neuroscientist and memory expert György Buzsáki of Rutgers University in Newark, N.J., calls the new research a “very imaginative and careful study. Predicting the spatial position with an imaging method in the human brain is a feat itself.”

The invasive mind-reading potential of the new study may seem frightening, but not to worry, Maguire says. The new study was conducted on carefully controlled spatial memories, which are different from complex episodic memories, such as recollections of a favorite childhood pet or a wedding day. Spatial memories are generally thought to be a more primitive type of memory that refers to location within an environment.

And the prediction algorithm only works after multiple training sessions of a person recalling particular spatial memories.

“So it is not the case that we can put someone in a brain scanner and simply read their private thoughts,” Maguire says.

Maguire says it will be interesting to see how these memory-reading technologies develop in the future. For now though, she says, any debates about social and ethical implications are “premature.” Private memories are still safe from prying Muggle eyes, but watch out for a wizard with a pensieve.