Sam Ting tries to expose dark matter’s mysteries

Physics Nobel laureate's space-based detector is analyzing billions of cosmic rays

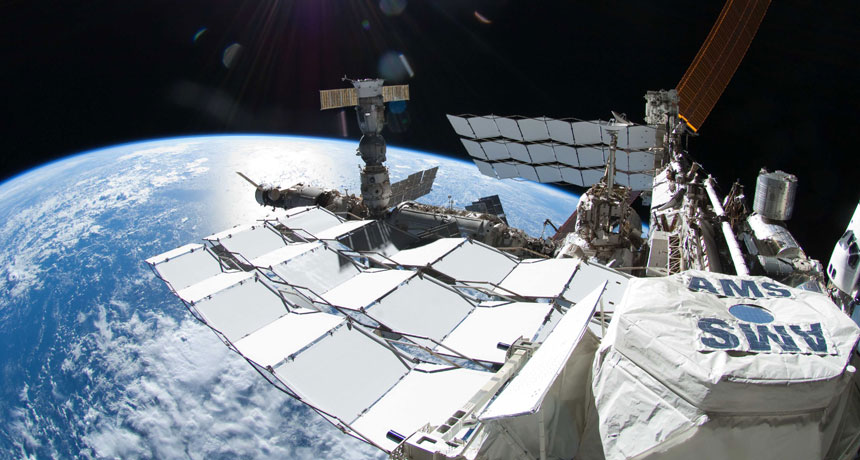

EYES ON THE INVISIBLE PRIZE Designed to detect cosmic rays, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer cruises above Earth on the International Space Station.

NASA

In the near vacuum of outer space, each rare morsel of matter tells a story. A speedy proton may have been propelled by the shock wave of an exploding star. A stray electron may have teetered on the precipice of a black hole, only to be flung away in a powerful jet of searing gas.

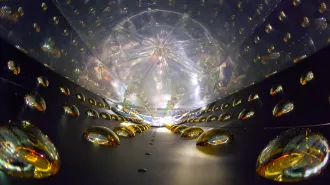

Since 2011, the International Space Station has housed an experiment that aims to decipher those origin stories. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer has already cataloged more than 60 billion protons, electrons and other spaceborne subatomic particles, known as cosmic rays, as they zip by.

Other experiments sample the shower of particles produced when cosmic rays strike atoms and molecules in Earth’s atmosphere. But the spectrometer scrutinizes pristine cosmic rays — some of which have traveled undisturbed over millions of light-years — from its perch some 400 kilometers above Earth. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer is by far the most sensitive cosmic ray detector ever to fly in space, and with a price tag of about $2 billion, it’s also the most expensive.

The detector’s unprecedented particle census could unmask the identity of dark matter, the mysterious, invisible substance that is five times as abundant in the universe as ordinary matter. Some of the cosmic rays snatched by the instrument may have been produced by particles of dark matter colliding and annihilating each other in the center of the galaxy.

The spectrometer could also help scientists determine why planets, stars and other structures in the universe are made of matter rather than antimatter. Particles of antimatter have the opposite charge as their matter counterparts but are identical in nearly every other way. It’s uncertain why most of the antimatter particles disappeared just after the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. Physicists would love to discover primordial antimatter to test their theories on what hastened its demise.

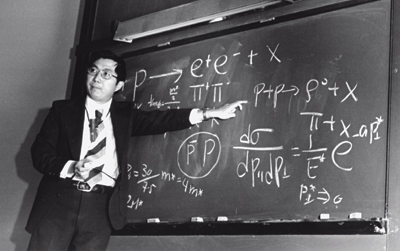

Nearly four years into the mission, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer is delivering precise data and arguably providing a few hints about the nature of dark matter. But it’s unclear whether the mission will ever deliver on its ambitious goals. Cosmic rays are charged particles that get whipped around by magnetic fields, so they don’t travel in straight lines and cannot be traced back to their source. To pin the origin of particular cosmic rays to dark matter, scientists will have to rule out every other possible explanation. Critics say the chances of identifying dark matter are very slim. And finding primordial antimatter, they say, is nearly impossible.Such criticism barely registers with the mission’s leader, particle physicist Samuel Ting. The 79-year-old Nobel laureate has made a career of designing elegant experiments and, despite frequent opposition, successfully lobbying to get them built. Then he has patiently collected and analyzed data, meticulous to the extreme, before revealing the often-impressive findings. Though results may come later than most scientists would prefer, Ting is confident that conducting a powerful particle physics experiment in space will expand scientists’ understanding of the cosmos.

Full focus

Ting’s home base these days is at CERN, the European physics laboratory outside Geneva that partially funds the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer and is home to the mission’s command center. But on one afternoon in December, Ting is at MIT, where he still runs a lab. His office is housed in a building marked with a capital J that honors his Nobel Prize–winning discovery, the J particle. The alleged reason for Ting’s U.S. visit was to meet with a contractor to discuss renovating his Cambridge, Mass., home. But the contractor confab was brief. For Ting, matters outside of physics take a backseat.

“You really can’t get into this field without thinking this is the most important thing in your life,” Ting says.

Two high-definition monitors on his office wall reinforce his obsession. One shows a live feed from the space station, a grainy black-and-white image capturing the spectrometer and our imperceptibly spinning planet below. The other screen plays a computer reconstruction of the instrument in action. In nearly real time, cosmic rays pass through its magnet, triggering a slate of sensors that determine the particles’ identity, energy and trajectory.

Ting doesn’t have a background in astrophysics, but he has plenty of experience sorting through a glut of particles to find really cool stuff.

He pulls up a 1965 New York Times article on his computer. The article describes Ting’s first major discovery, when he, Leon Lederman (who won the 1988 Nobel Prize in physics) and colleagues produced and detected antimatter nuclei for the first time. (A team at CERN made a similar discovery soon after.) It’s difficult enough to observe single particles of antimatter because they disappear in a burst of energy when they encounter ordinary matter. Ting and Lederman managed to observe bound pairs of antimatter particles, called antideuterons, in a particle accelerator at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, N.Y.

Ting’s childlike curiosity quickly comes across as he describes the possibility that antideuterons and other large chunks of antimatter, relics of the first moments after the Big Bang, could be drifting in the cosmos, waiting to be found. But beneath the inquisitiveness is also an extreme confidence, even an arrogance, that he alone knows the way to probe the big questions.

Those qualities were on display in the early 1970s when Ting became interested in quarks, tiny parcels that compose such particles as protons and neutrons. Physicists had proposed and discovered evidence for three kinds of quarks. But Ting, eager to unravel every detail about matter’s makeup, joined a group of physicists who wondered whether there were other quark varieties. He proposed colliding particles at high energies, which would create short-lived matter that ultimately decayed into electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons. By analyzing the electrons and positrons, he could determine the composition of the intermediate particles.

Ting says many physicists scoffed at his proposal; they believed that the three quarks could explain all the more complex particles in physics. Multiple labs turned him down before Brookhaven let him give it a try.

In the summer of 1974, Ting and his team saw convincing signs of a new subatomic particle with an unusual composition. But Ting refused to release the data until he was sure everything was correct. He split his team into two groups that independently analyzed the data again and again. Only in November of that year, when a colleague at a meeting told Ting that particle physicist Burton Richter had seen the same signal at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, did Ting share his finding. The confirmation of a fourth quark, the charm, embedded in a particle that Ting called J and Richter called Psi earned Ting a share (with Richter) of the 1976 Nobel Prize in physics. Ting’s experimental design skill, combined with large doses of meticulousness, smarts and stubbornness, had netted him the ultimate physics honor. He was 40 years old.

From there, Ting kept pursuing big projects. In the late 1980s, he organized a team to design a detector for the multibillion-dollar Superconducting Super Collider, an 87-kilometer-around particle accelerator slated for construction near Waxahachie, Texas. Ting wanted to build a $750 million instrument; the U.S. Department of Energy said the detector should not cost more than $500 million. So Ting quit. “He was very determined to do it his way,” says Gary Sanders, a high-energy physicist and former Ting graduate student who was part of that team.

In 1993, Congress dealt American physicists a devastating blow by canceling the Super Collider. Ting, however, had moved on. In 1994, he pitched perhaps the most ambitious project of his career.

Like his first major experiment, it would hunt for antideuterons and other antimatter nuclei. And similar to his Nobel-winning research, it would use electrons and positrons as probes to identify undiscovered parent particles. Except instead of sorting through shrapnel created in carefully orchestrated particle collisions, he wanted to go after particles produced naturally in the universe. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer experiment would collect and analyze particles in space.

Both NASA and the Department of Energy, the same agency that rejected Ting’s plan for the detector in Texas, pledged their support.

From lab to liftoff

Scientists have studied cosmic rays for a century in hope of learning about the objects that produce them. But Ting’s proposal offered the rare chance to create a robust census of cosmic rays from well above Earth’s meddlesome atmosphere. Most previous experiments took place on balloons, which fly only briefly and don’t leave the atmosphere, or on the ground, forcing scientists to analyze cascading showers of particles triggered by cosmic rays striking atoms in the atmosphere.

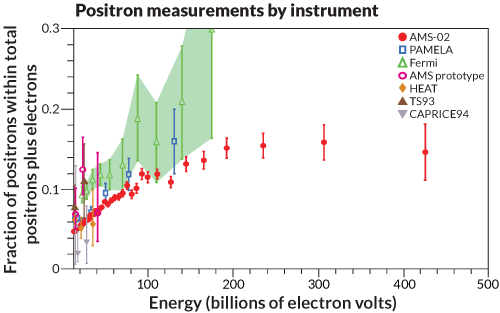

Those past experiments still delivered some tantalizing results. In 1997, the High-Energy Antimatter Telescope, or HEAT, a cosmic ray detector tethered to a high-altitude balloon, revealed an unexpectedly high concentration of positrons in space. At the time, physicists didn’t know of many processes in the universe that could produce positrons, so theorists quickly came up with some ideas. The most intriguing possibility was that the positrons were created by particles of dark matter in the galaxy. Though the dark matter particles would be invisible, they would occasionally collide and annihilate each other to produce gamma radiation and detectable particles, including electrons and positrons. If these dark matter theories were correct, then a precise measurement of cosmic ray positrons would enable physicists to pin down the nature and mass of dark matter particles.

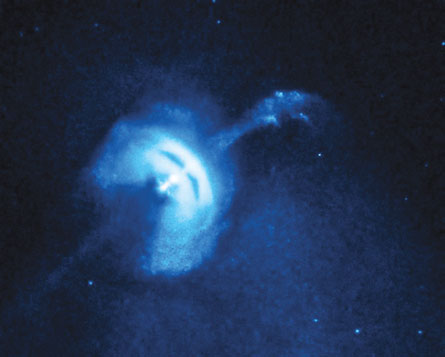

But dark matter wasn’t the only explanation. Other theorists proposed positron-forming mechanisms that have far less relevance for deciphering the universe. Atop the list were pulsars — dense, rapidly spinning cores left over after massive stars explode. A pulsar’s rapid rotational speed generates an intense electromagnetic field strong enough to rip electrons from its surface. Those electrons interact with photons and create pairs of electrons and positrons. Calculations suggested that just one or two pulsars, which are difficult to detect, within hundreds of light-years of the solar system would be enough to litter Earth with positrons.

Despite the intriguing quandary exposed by HEAT, some scientists doubted that the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer could add much to the positron origin debate or resolve any big physics mysteries. But Ting was determined to see his project fly. He assembled a 16-country collaboration to divide the work and the ballooning costs. When the 2003 explosion of the space shuttle Columbia led NASA to rescind its offer of a ride to the space station, Ting lobbied members of Congress, teasing at the wonders that could be hidden in cosmic rays and stressing the International Space Station’s not-so-stellar reputation for housing serious science.

“If you told Sam that to get what he wanted he had to win the Indy 500, he’d become the world’s best race car driver,” says Richard Milner, the director of MIT’s Laboratory for Nuclear Science, who oversees Ting’s group. Ting wouldn’t let up on government officials in Washington, even as many of his collaborators focused on other projects.

He was very persuasive, says Kay Bailey Hutchison, at the time a U.S. Senator from Texas. She says Ting convinced her and others that the mission was worth the cost and safety concerns of extending the beleaguered shuttle program. “He’s such a visionary,” she says. She was inspired enough to switch appropriations subcommittees to find funding for the project. In October 2008, President George W. Bush signed a bill adding shuttle flights so that the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer would hitch a ride on one of them. “Without [Ting’s] absolute unwillingness to give up, we would not have gotten it,” Hutchison says.

By the time Ting’s brainchild reached the space station in May 2011, a couple of space-based cosmic ray experiments had beaten his spectrometer to the punch. In 2008, PAMELA, a cosmic ray detector attached to a Russian reconnaissance satellite, revealed the same positron excess hinted at by HEAT. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which also carries a cosmic ray detector, came up with similar results in 2011. Neither probe discerned the source of the positrons, however.

Ting broke his silence with a news conference at CERN in April 2013. After again employing two separate teams to comb through the data, he confirmed the positron excess detected by HEAT, PAMELA and Fermi (SN: 5/4/13, p. 14). Analyzing the properties of 6.8 million positrons and electrons, Ting’s team found that the number of positrons keeps rising as the particle energies increase. The clear excess of positrons, Ting said, reinforces that something relatively nearby must be producing them. He pushed the dark matter explanation but admitted it was not the only possibility.

Ting returned for another news conference in September. This time, after poring over 10.9 million positrons and electrons, Ting’s team pinpointed the energy, about 275 billion electron volts, at which the concentration of positrons stops increasing (see graph above). That’s an interesting number, says Peter McIntyre, a high-energy physicist at Texas A&M University in College Station, because it indicates that the mass of hypothetical dark matter particles limits the energy of the positrons they can produce. Theorists could use the peak positron energy to estimate dark matter’s mass. But again, the experiment did not come close to proving that dark matter actually produced the positrons.

In fact, some physicists argue that the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, despite its unmatched particle-detecting prowess, can never definitively distinguish between dark matter annihilation, pulsars or a yet-to-be-discovered process that might be producing those surplus shards of antimatter.“A pulsar could explain any observation that AMS could ever make,” says Gregory Tarlé, a particle astrophysicist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. No matter what the positron data, physicists will not be able to definitively isolate the alleged signal of dark matter, he argues.

Katherine Freese, a theoretical astrophysicist at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics in Stockholm, agrees that conclusively proving dark matter from positrons will be very difficult. “My bet is on pulsars,” she says.

Other experiments also suggest that AMS has a slim chance of making a compelling case for dark matter. In a study posted online in January at arXiv.org, physicists pored over Fermi telescope measurements to look for gamma radiation, which should also be produced when dark matter particles annihilate each other. The data ruled out most dark matter collision mechanisms proposed by theorists. And in December, scientists with the Planck satellite announced that their survey of the universe’s most ancient light revealed no signs of detritus from colliding dark matter, which if self-annihilating now also should have been when the cosmos was young (SN: 12/27/14, p. 11).

Ting says he pays about as much attention to other experiments as he does to his critics. He monitors the scientific literature, but doesn’t put much stock in blanket conclusions based on one set of data. “I learned a long time ago: Only look at your own experiment,” he says.

He expects to learn more by studying positrons at higher energies. If the mass of a dark matter particle is, say, one trillion electron volts, then it probably wouldn’t produce positrons with more than a quarter of that energy. So if the positron concentration falls off a cliff after the newly identified peak, Ting says, that would suggest a dark matter origin. Pulsars, on the other hand, should produce positrons with a spectrum of energies that wouldn’t drop so precipitously.

Within the next year or two, the AMS team will release its first analysis of antiprotons, antimatter particles that Ting says are too heavy to be manufactured by pulsars but should be produced in dark matter collisions. Ting calls the preliminary results “intriguing.” But of course, he won’t offer more until all the cross-checks are complete.

He’s confident that future measurements will allow him to definitively pin down the origin of positrons, whether from dark matter or something else.

Even if the dark matter picture remains muddled, there is a possibility that AMS will detect primordial antimatter. One of the biggest mysteries in physics is why matter won out in a universe that presumably began with equal parts of matter and antimatter. Ting hopes to find complex antimatter — perhaps antihelium (two antiprotons and two antineutrons) or antideuterons — that was forged just after the Big Bang. Tarlé and other scientists say the chances of detecting these antinuclei are extremely low because the antimatter would have to navigate through the matter-rich galaxy and solar system without being destroyed.

Ting is undeterred. Gathering insights about the cosmos takes time. Anticipating that funding will run as long as the space station operates, Ting simply wants to see what nature throws at him. “If you don’t look,” he says, “you do not know.”

This article appeared in the March 21, 2015, issue of Science News under the headline, “Eyes on the invisible prize.”