Normal 0 false false false MicrosoftInternetExplorer4 Normal 0 false false false MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

BARCELONA, SPAIN — Newly released images of the seafloor near Ireland depict scattered tidbits of history both old and new, from gouges scraped by icebergs during the last ice age to the wreckage of the Lusitania and hulks of German U-boats sunk by the British navy at the end of World War II.

The territorial waters of Ireland cover an area exceeding 890,000 square kilometers, about 10 times the size of the country’s land area, said John Joyce of the Marine Institute in Dublin, speaking July 21 during the Euroscience Open Forum in Barcelona, Spain.

In 1996, scientists began scanning the seafloor with sonar as part of the Irish National Seabed Survey, one of several similar programs underway in Europe, where territorial waters of the continent actually include more area than its landmass does, Joyce said. When the Irish program began, the effort was the largest civilian underwater mapping effort in the world, Joyce added.

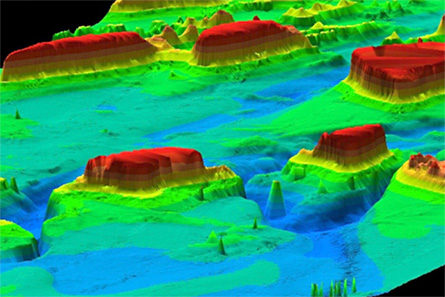

Most of the images collected during the survey’s early days come from deep water, where sonar-equipped ships could more easily navigate and where each sonar scan could cover more territory. Among the deep-sea discoveries are broad troughs carved into the ocean floor at or near the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago.

The survey also revealed a 20-kilometer-long, 20-to-30-meter-deep trench off the coast, a hint that a suspected but previously undiscovered geological fault lies beneath the seafloor there, says John Evans, co-director of the survey at the Marine Institute’s headquarters in Oranmore, Ireland. “Nobody knew this was there except the local fisherman” who capitalized on the bounty of fish drawn to the submarine feature, he notes.

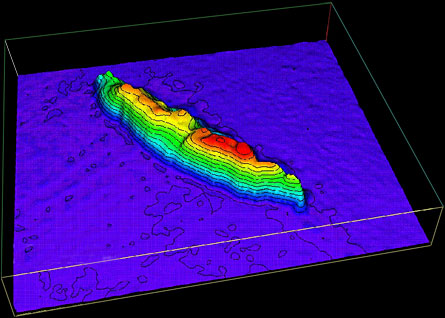

The seabed scans have revealed more than 200 anomalies either known or believed to be shipwrecks. Many of those were previously undiscovered, and others sit in spots other than where they were believed to have sunk, Evans says.

Modern-day additions to the deep-sea landscape near Ireland include the Lusitania, an ocean liner whose sinking by a German submarine on May 7, 1915 helped draw the United States into World War I.

The ocean bottom north of the country also is home to a large number of German U-boats towed to sea and sunk by the British navy after World War II had ended, Joyce said.

Although the Lusitania’s final resting place was long known, no previous surveys had stumbled across these old subs, he noted. Resolution of the new sonar scans would allow researchers to spot an object the size of a refrigerator at a distance of 3 kilometers, he added

In some areas, immense dune fields cover the seafloor. Images of these previously undiscovered dunes, as well as future scans of the same features, will enable scientists to better understand the environmental forces that sculpt the ocean bottom there and how quickly — or how slowly — they work.

The Irish survey is now about 90 percent complete, Joyce reported. Today, scientists are mapping the shallow waters around Ireland using an aircraft-mounted laser altimeter. The light from that device penetrates a dozen or so meters into the water, enabling the researchers to quickly and accurately map areas that ships can’t reach. “The Irish coast is quite fragmented, and many areas are difficult to get into,” Evans adds.

Every year, the researchers visit some previously surveyed deep-sea areas to collect sediment samples, take detailed measurements of water properties and generally assess the seafloor environment, Evans says. All data collected during the survey are available at no cost to scientists and commercial interests. More than 50 research projects in areas such as geology, oceanography and biology are now under way, he notes.

Data from the Irish survey could be a boon to more than just navigation and wreck divers. Companies seeking to exploit wave power as a source of alternative energy could use the data to help select suitable sites for their generators, Joyce contended. The seas off Ireland are some of the roughest in the world, and earlier this month researchers deployed a one-quarter-scale prototype device to assess the region’s potential to generate environmentally friendly energy.