Smell test may detect autism

Kids with disorder inhale foul odors as much as pleasing scents

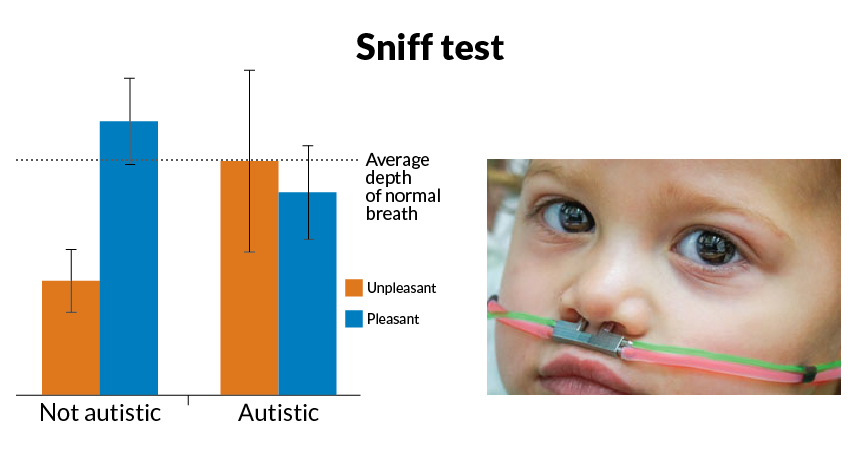

TAKE A BREATH Unlike kids without autism, kids with the disorder breathe in just about as deeply whether they’re smelling unpleasant odors (rotten fish, sour milk) or pleasant ones (roses, shampoo), a new study suggests. Researchers delivered scents via tubes hooked up to the children’s noses, and measured length and depth of inhalations.

Rozenkrantz et al/Current Biology 2015 (graph), Ofer Perl (image)