This South African cave stone may bear the world’s oldest drawing

The 73,000-year-old line design could have had special meaning for its makers, researchers say

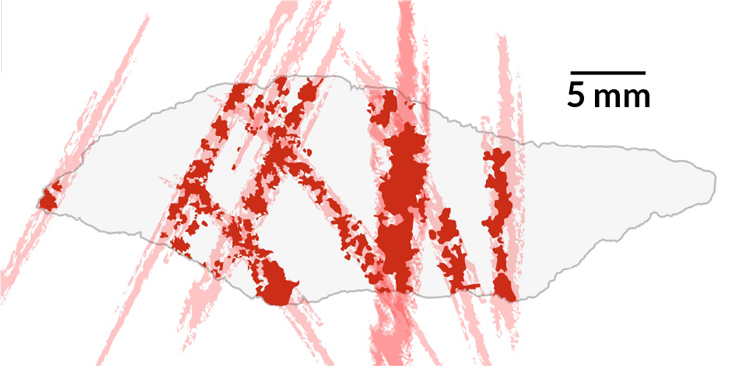

DRAWN OUT The 73,000-year-old red marks on this stone from a South African cave are remnants of a crosshatched design that researchers regard as the earliest known drawing.

Craig Foster

A red, crosshatched design adorning a rock from a South African cave may take the prize as the oldest known drawing.

Ancient humans sketched the line pattern around 73,000 years ago by running a chunk of pigment across a smoothed section of stone in Blombos Cave, scientists say. Until now, the earliest drawings dated to roughly 40,000 years ago on cave walls in Europe and Indonesia.

The discovery “helps round out the argument that Homo sapiens [at Blombos Cave] behaved essentially like us before 70,000 years ago,” says archaeologist Christopher Henshilwood of the University of Bergen in Norway.

His team noticed the ancient drawing while examining thousands of stone fragments and tools excavated in 2011 from cave sediment. Other finds have included 100,000- to 70,000-year-old pigment chunks engraved with crosshatched and line designs (SN Online: 6/12/09), 100,000-year-old abalone shells containing remnants of a pigment-infused paint (SN: 11/19/11, p. 16) and shell beads from around the same time.

The faded pattern consists of six upward-oriented lines crossed at an angle by three slightly curved lines, the researchers report online September 12 in Nature. Microscopic and chemical analyses showed that the lines were composed of a reddish, earthy pigment known as ocher.

Crosshatched designs similar to the drawing have been found engraved on shells at the site, Henshilwood says. So the patterns may have held some sort of meaning for their makers. But it’s hard to know whether the crossed lines represent an abstract idea or a real-life concern. Some modern hunter-gatherer societies create abstract-looking designs that actually depict animals, objects or people, he says.

Whatever the drawing’s original significance, it shows that Stone Age folk in southern Africa communicated something they considered important by applying crosshatched patterns to different surfaces, says archaeologist Paul Pettitt of Durham University in England. “If there is any point at which one can say that symbolic activity had emerged in human society, this is it.”

But archaeologist Maxime Aubert of Griffith University in Southport, Australia, isn’t so sure. Henshilwood’s team can’t exclude the possibility, for example, that the apparent drawing accidentally resulted from people sharpening the tips of pigment chunks on rocks to make Stone Age crayons, Aubert says.

Henshilwood disagrees. Experimental reproductions of the crosshatched pigment pattern, drawn on rocks like those at the South African cave, indicate that the lines were intentionally produced and were originally darker and better defined, he says. Previous evidence also suggested that ancient humans at the cave used pigment as a glue ingredient and possibly as a sunscreen. But the experimental drawings produced too little powder to use as a glue additive or a sunblock. Ancient pigment wielders appear to have wanted only to draw a design on the stone.

Henshilwood’s team has demonstrated how to identify deliberate drawings at ancient human sites by excluding other possible explanations for making pigment strokes, says archaeologist Gerrit van den Bergh of the University of Wollongong in Australia. “It is likely that further evidence for early symbolic behavior will be found in the very near future.”