Swine flu vaccination should target children first

With influenza season looming, an analysis models the H1N1 virus’s potential spread and various programs to contain it

- More than 2 years ago

View a video modelling how H1N1 will spread in 2009 at the bottom of this article.

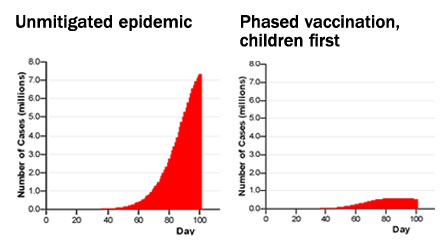

If the H1N1 flu outbreak doesn’t peak until midwinter, it could be curtailed with a staggered vaccination program that begins with children and ultimately targets 70 percent of the population, researchers report online September 10 in Science.

From mid-April to August 30, a total of 9,079 hospitalizations and 593 deaths associated with the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Experts aren’t sure when seasonal flu activity will peak this year, but cases of H1N1 influenza have flared in the weeks since school began. For example, in a briefing on September 8, Anne Schuchat, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, reported that about 25,000 children were dismissed from schools on September 4 because of the flu.

A new analysis by infectious disease specialists and biostatisticians models the potential spread of the flu and then looks at the effectiveness of various proposed vaccination programs.

“We had no idea how vaccinating would work in the teeth of the epidemic,” says study coauthor Ira Longini, a biostatistician at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Institute at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle.

About 30 to 40 percent of transmission will occur in households and about 20 percent in schools, the researchers estimate. Using numbers from an outbreak at a private New York City school this spring, the model suggests that a typical school-age child will infect an average of 2.4 other kids at his or her school. The team also found that the flu will probably spread through September and peak in mid- to late-October.

Current estimates suggest that between 45 million and 52 million doses of vaccine will be ready by mid-October, with another 195 million by the end of the year. Longini and his colleagues find that because children will experience the highest infection rates they should receive vaccines first. Vaccinating other at-risk groups, such as health care workers and those with compromised immune systems, is also important. Given the pattern of spread among connected people, the researchers suggest that vaccinating 70 percent of the U.S. population will contain the virus.

“At first we were happily surprised,” that vaccinating children first could effectively curtail the flu’s spread, Longini says. But in order for this plan to work, the vaccine would have to arrive earlier than expected and the spread would have to hit its high point later than expected. “The more likely scenario this year is that it could be peaking when the vaccine arrives,” he says.

Preliminary results based on three weeks of data from several vaccine trials suggest that one dose of the vaccine elicits a good antibody response in healthy young and middle-aged adults. The findings are “welcome and reassuring,” states an editorial by Kathleen Neuzil that appeared online September 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine along with the preliminary studies. Experts thought two does of the H1N1 vaccine might be necessary, which halves the number of people that can be vaccinated with a fixed amount of vaccine. Because children seem especially susceptible to the pandemic strain of H1N1, and because children generally have an inferior response to vaccines compared to adults, two doses may still be necessary for kids, notes Neuzil, of the allergy and infectious disease division at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

If the pandemic flu peaks earlier in October, a vaccination program that targets children would need to be launched as soon as possible, the new analysis in Science concludes.

The new work is well done and highlights the importance of vaccinating children, says Jan Medlock, a mathematical biologist at Clemson University in South Carolina. Close quarters with multiple peers and more liberal personal hygiene policies make kids more likely to carry germs. Vaccinating kids protects them and reduces disease transmission, protecting others, he says.

Compared with most influenza viruses, the H1N1 pandemic flu has also caused more disease in people under age 25 than in older people, perhaps because older people have some preexisting immunity to this strain. That offers another reason to focus initial vaccine efforts on younger people.

While prevalent — by mid-July, 99 percent of all tested flu in the United States was pandemic H1N1, according to the CDC — the virus appears not to have changed much since the spring. This offers hope, researchers say, that vaccines based on spring strains will be effective against what is brewing now.

Modeling the Influenza Pandemic from Science News on Vimeo.

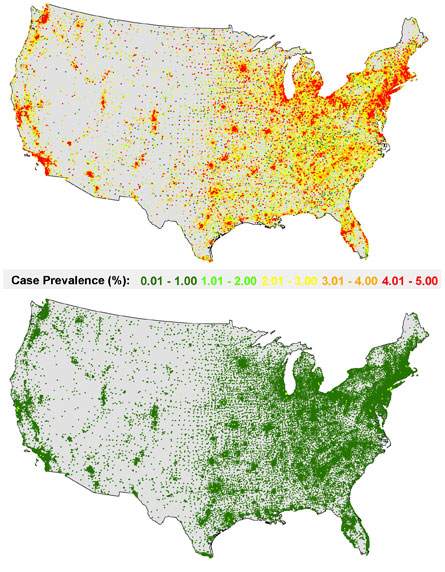

A model simulates how the 2009 H1N1 virus may spread in the United States if there is no vaccination intervention (top) vs a vaccination effort that covers 70 percent of the population, with no particular age or risk group targeted (bottom).

Launching an aggressive vaccination program that targets children and begins before the H1N1 outbreak peaks could contain the spread of the virus.

Video: Ira Longini