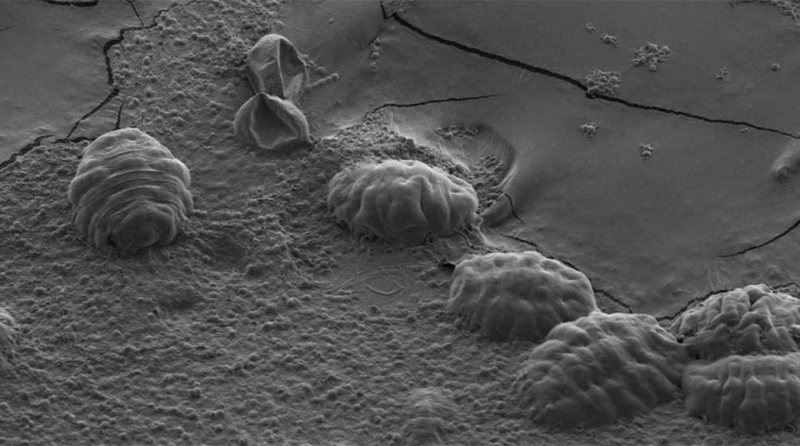

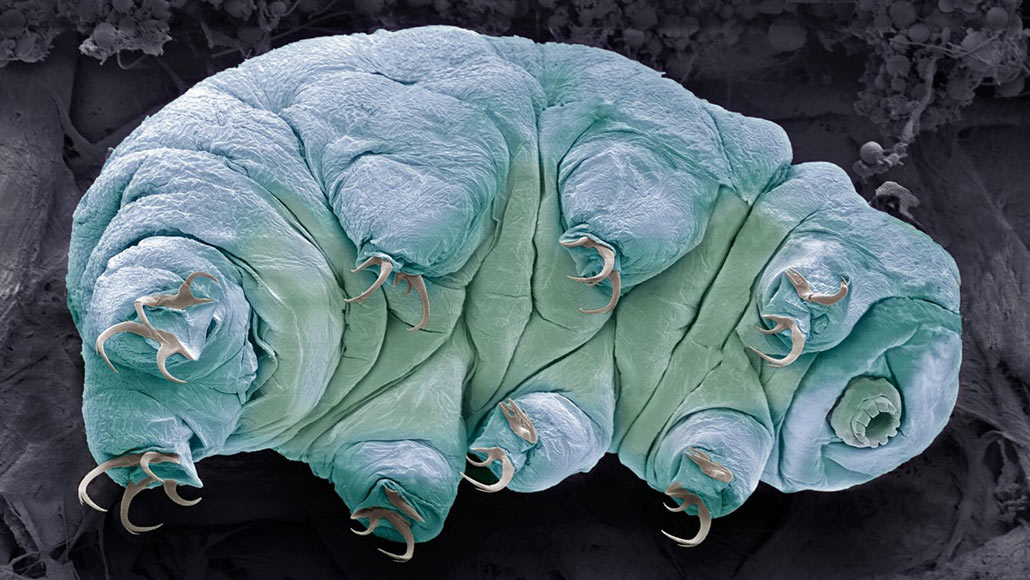

Some species of tardigrades (an SEM image of one shown) can survive doses of radiation up to 1,000 times that which would kill a human. How they do it has been a mystery, but scientists have deciphered one clue of their secret to survival.

STEVE GSCHMEISSNER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Alamy stock photo