A tiny mystery dinosaur from New Mexico is officially T. rex’s cousin

It took decades to ID the 92-million-year-old tyrannosaur, newly named Suskityrannus hazelae

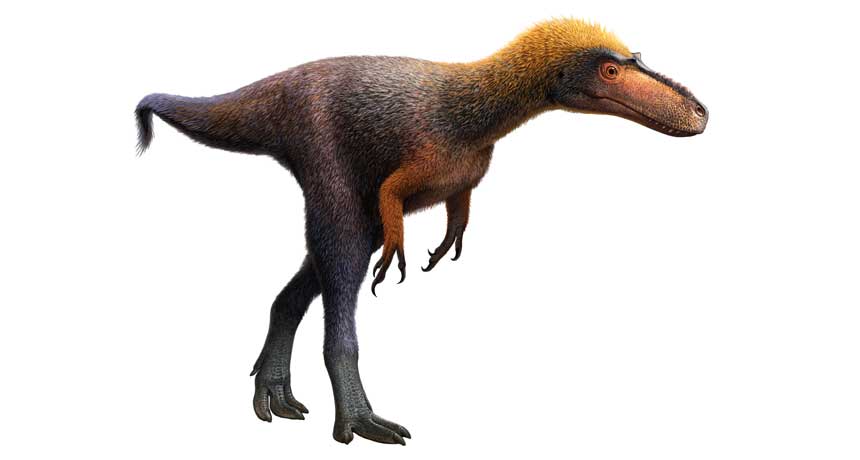

MISSING LINK A newly identified dinosaur species called Suskityrannus hazelae (illustrated) offers a glimpse into the evolution of apex predators like Tyrannosaurus rex just before they got really big.

Andrey Atuchin